News:

The Mystery of the Painting in Gallery 634

By Graham Bowley

New evidence suggests a 17th-century work, on view for years at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, was once owned by a Jewish art dealer who fled the Nazis.

“The Rape of Tamar” is a masterpiece, but is it also stolen?

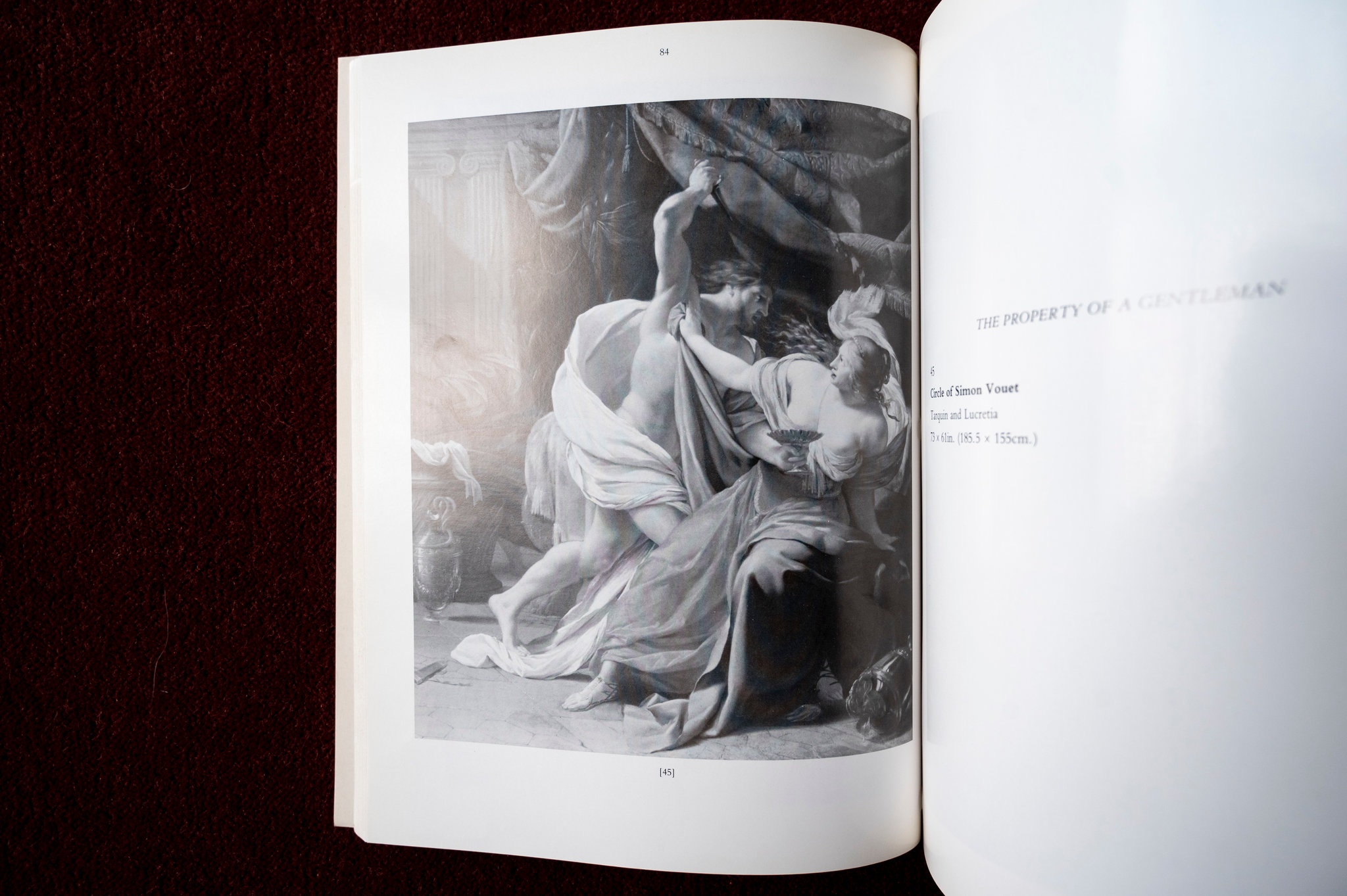

For years, a large, richly colored painting depicting a moment of sexual violence has stopped visitors in Gallery 634 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Once viewed as an image of Tarquin attacking Lucretia, as in Roman legend, the 17th-century work attributed to Eustache Le Sueur has more recently been described as a portrayal of the rape of Tamar from the Old Testament.

Now newly discovered evidence suggests the painting’s history is as painful as its theme.

Old court records indicate the painting, purchased by the Met in 1984, is likely the same one a Jewish art dealer, Siegfried Aram, left behind when he fled Germany as Hitler took power in 1933.

The records, which recount the dealer’s unsuccessful effort to reclaim his painting for more than a decade after the war, were discovered by a researcher and photographer, Joachim Peter, who has spent years studying the history of Heilbronn, the German city where Mr. Aram once lived, including the treatment of its Jews and the devastation from Allied bombing.

Mr. Aram, the records show, argued in courtroom after courtroom that he was a victim of the Nazi era, a Jew put in an impossible position because of the persecution launched by Hitler. First forced to sell his home under duress for too little money to a German businessman, Oskar Sommer, he argued that Mr. Sommer then illegally walked off with his artwork as well.

“The Rape of Tamar,” circa 1640, attributed to Eustache Le Sueur. The Met purchased it from a trio of dealers in 1984.

Now, in response to questions from The New York Times, the Met is reviewing the painting’s history of ownership to determine what, if anything, it should do to resolve the situation.

“This is important new information that is worthy of a detailed investigation, which we will begin immediately,” the museum said in a statement. “The Met has a long history of working with claimants to research and find a just and fair solution in cases of art wrongfully appropriated during the Nazi era.”

Mr. Sommer’s family brought the painting to auction at Christies’ in London in 1983, two of Mr. Sommer’s daughters told The Times. It sold as Lot 45 to a trio of dealers for 108,000 pounds, or about $485,000 today. Now it could be worth as much as $1.5 million, one dealer estimated.

The listed provenance at auction made no mention of Mr. Aram, who had died five years earlier. It was described simply as “the property of a gentleman,” without any reference to previous owners.

The dealers had bought the painting at a Christie’s auction in London in 1983. The Christie’s catalog carried the painting as “Tarquin and Lucretia” and listed it as “the property of a gentleman.”

The Met bought it months later from those dealers for an undisclosed price. The museum’s officials concluded at the time that the painting “has no known provenance prior to its appearance at auction at Christie’s, London, 2 December 1983.”

As much as the story of the painting is a question of ownership, it is also a vivid illustration of how much less equipped and attentive the world once was on the issue of art lost during the Nazi era.

Authorities after the war returned hundreds of thousands of artifacts that had been lost through displacement or Nazi looting. Museums and the art market tried to review works that came to market with patchy histories. But it was an imprecise process, without the digital databases that are so useful today.

Experts say that as time moved on, many people assumed, incorrectly, that most items had been returned.

“By the ’70s, ’80s, few people thought about those things anymore,” said Lynn H. Nicholas, an historian and expert on Nazi-looted art. “Unless somebody made a noise, it would not have even occurred to a dealer to go back and check.”

A Forgotten Dispute

Mr. Aram’s efforts might have remained buried inside the state archives in Baden-Württemberg were it not for Mr. Peter, who recreated, document by document, the dealer’s fight for his painting.

A portrait of Siegfried Aram by Warren Chase Merritt in 1938.

A postcard from the 1950s shows the Schapbach villa, the property where the disputed painting had once hung.

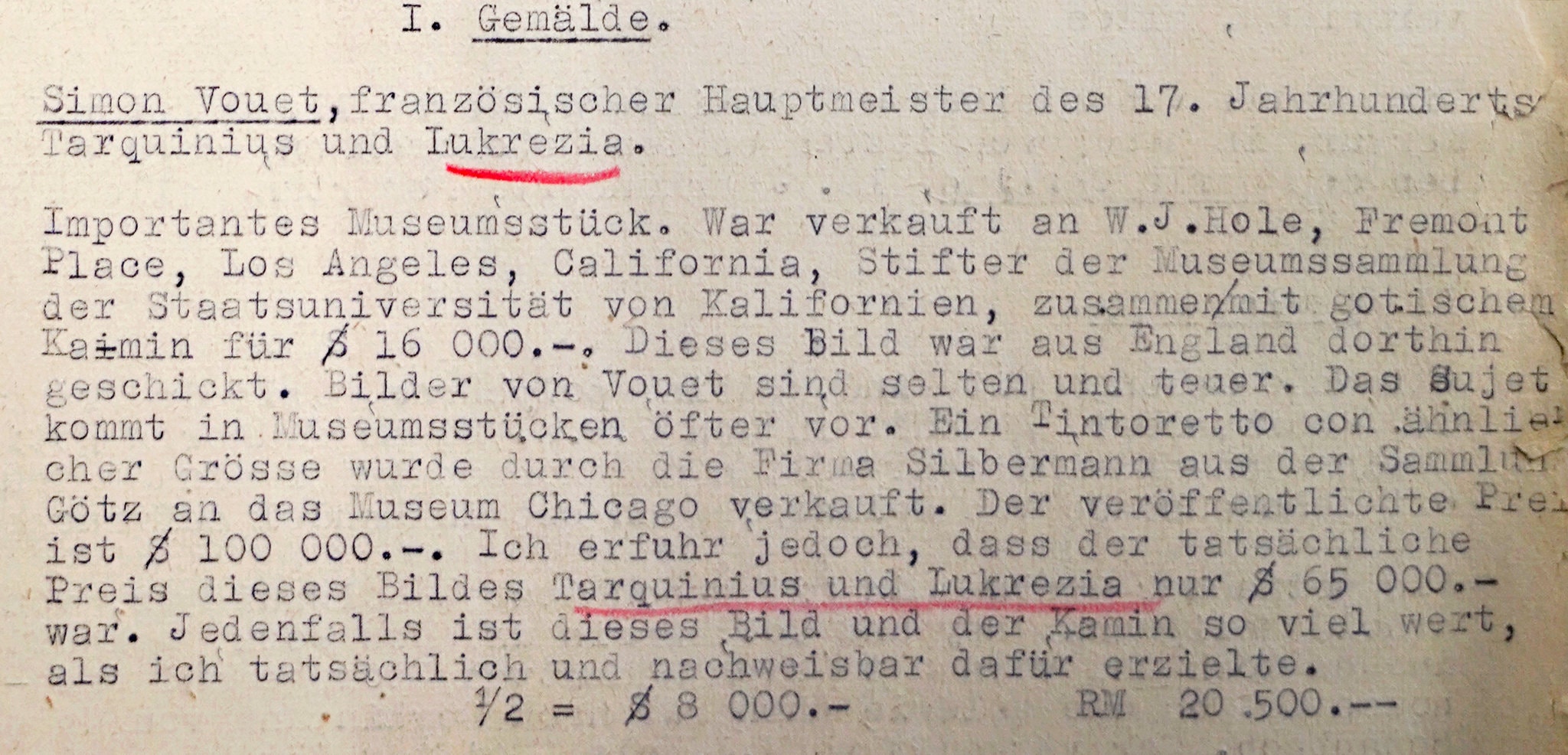

Mr. Aram had purchased the painting in London in the mid-1920s, according to court filings he made. He considered it to be “Tarquin and Lucretia” by the court painter for King Louis XIII of France, Simon Vouet, in whose studio Le Sueur had his early training.

When Mr. Aram fled Germany, his mother, Thekla, stayed in Berlin, tasked with selling the family’s properties, including Mr. Aram’s large home in Schapbach, in the Black Forest. It was a time when the Nazis were beginning to promote the boycott of Jewish businesses and to target enemies of the regime.

To sell the home, a distinctive property that later became the subject of a postcard, Mr. Aram’s mother negotiated with Mr. Sommer, a department store owner. The 1933 sales contract excluded the painting, which Mr. Aram said he had already arranged to sell to a collector in California. (The sales contract and a certified translation of the painting’s bill of sale to the American support that account and were later submitted in court by Mr. Aram’s lawyer.)

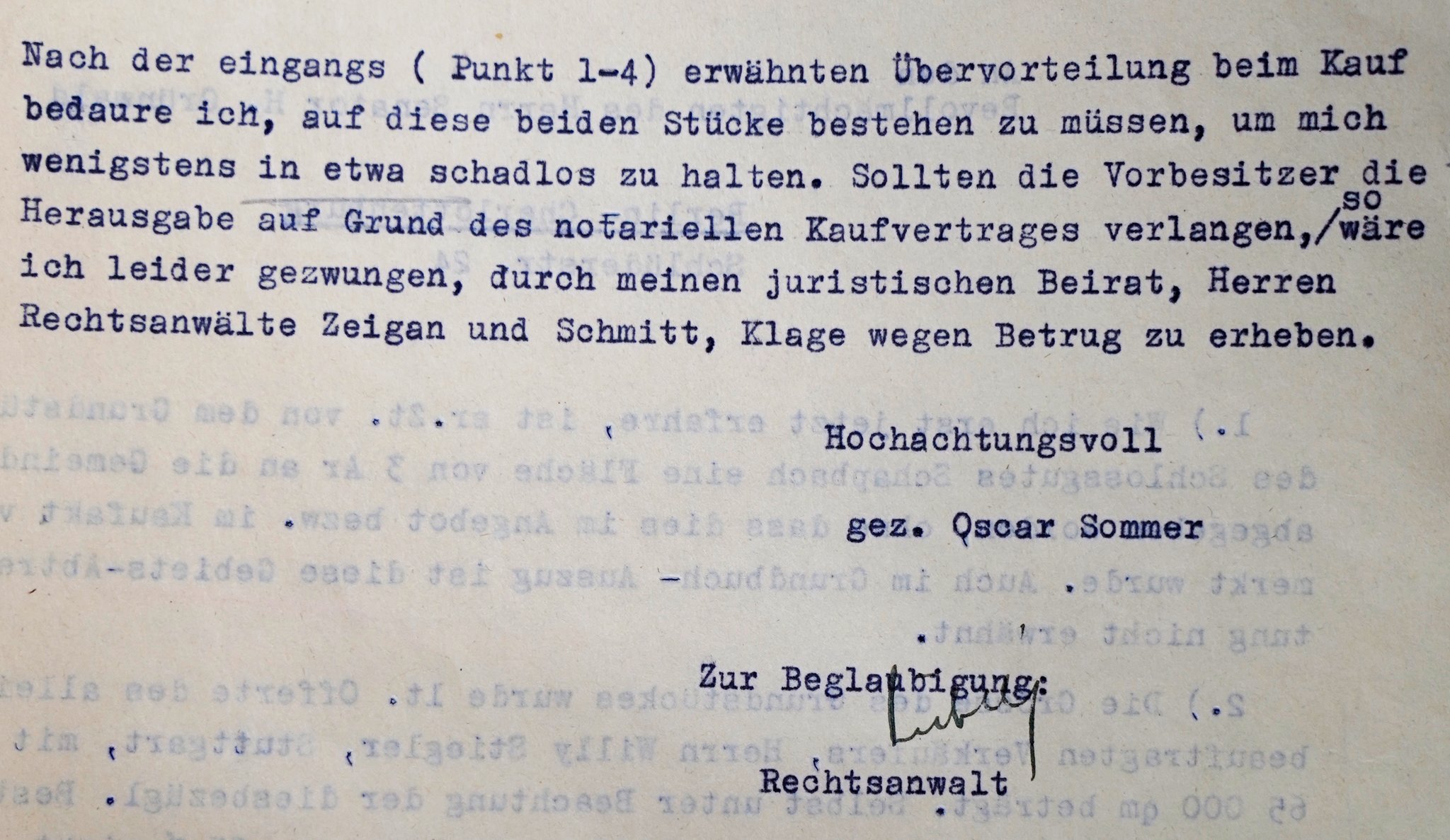

But Mr. Sommer said he was keeping the painting. He complained that the property was smaller than described, that he had not been properly informed of any exclusions and that Mr. Aram’s mother had tried to remove other items that were part of the deal.

Excerpt of a 1933 letter from the businessman who bought Mr. Aram’s villa stating that he would keep the painting “Lukretia,” or otherwise he would be forced to sue for fraud.Credit...via State Archives of Baden-Württemberg

Mr. Sommer also threatened to sue.

In interviews, Mr. Sommer’s daughters denied their father might have done anything to exploit the vulnerabilities of Jews. They said, rather, that he had spoken of having sheltered persecuted Jews. A German historian, Gabriele Clemens, said Mr. Sommer, who died in 1966, once resigned a post in protest of the Nazis. There is a plaque commemorating his life in his hometown, Trier, where his family has run a department store for generations.

But Mr. Aram, in court papers, argued that he had been taken advantage of because of his religion. The property, an estate with multiple buildings, that he sold to Mr. Sommer for 70,000 Reichsmarks was resold five years later for 195,000. Mr. Aram said his mother was so upset by the negotiations with Mr. Sommer that she tried to kill herself with sleeping pills before fleeing to Italy, where she died of cancer in 1934.

A description of the painting provided by Mr. Aram in his lawsuit. He wrote that he had already agreed to sell the painting to the American collector W. J. Hole. He valued it at $8,000.

Even in the United States, Mr. Aram felt pursued, according to his letters and court records. Nazi diplomats were tracking him, he wrote, and he feared they might try to spirit him back to Germany. He moved around a lot, to San Francisco, Los Angeles, Detroit, and finally New York, where he opened a gallery on East 57th Street in the late 1930s. He said in letters that someone once scratched swastikas on its windows and that he was beaten on the street by two men yelling anti-Semitic slurs.

Still, his profile as a dealer grew with major collectors and important museums, who often bought his inventory. And he never stopped battling to reclaim the painting that had hung in his home in Schapbach.

In postwar Germany, courts and government agencies oversaw the many claims brought by displaced Jews. Though Mr. Aram fought in several arenas, his case was never decided on the merits.

One German judge agreed he had never turned over the painting, but ruled the issue moot based on the erroneous assumption, fueled by Mr. Sommer, that it was no longer in the businessman’s possession. In an appeal, Mr. Aram received another $7,000 (about $70,000 today) from Mr. Sommer in a settlement over the house price, but the painting’s ownership remained in dispute.

A subsequent effort to sue the government failed when the state said that because it had not confiscated the painting, it could not be held responsible.

A Different Era

What, if any, of this history Christie’s understood at the time of the auction remains unclear.

Asked what research it had done on the painting’s history, Christie’s said in a statement that “details of previous ownership and title would have been assessed at the time.” It said its client confidentiality policy precluded disclosing who had consigned it for sale. It noted, though, that “in the early 1980s, the vital databases, registries, and digitized records necessary for thorough restitution research did not yet exist” and that today it has its own restitution department.

One of the dealers who bought the work, Guy Stair Sainty, said there was no indication at the time that the painting had a disputed ownership.

“You bought something in Christie’s or Sotheby’s and you didn’t even think about it,” Mr. Sainty said. “Unless you had a suspicion then, you had no reason to check, but nowadays we don’t buy a painting without looking.”

Restitution efforts revived greatly in the late 1990s as scholars like Ms. Nicholas focused on the scope of Nazi looting, and the fall of the Berlin Wall made clear the scale of displaced works in Eastern Europe. Some Jewish families began to pursue claims.

When the Met purchased the painting in 1984, its acquisition policies were not as strict as they are today. Today, for works likely to have been in German-occupied Europe between 1933 and 1945, the Met’s policy requires that “where information is incomplete for a gift, bequest or purchase, curatorial staff should undertake additional research prudent or necessary to resolve the Nazi-era provenance of the work.”

Joachim Peter, a photographer and researcher, in his spare time recreated, document by document, Mr. Aram’s fight for the painting.

It is unclear what would happen if the Met’s review concludes it is indeed Mr. Aram’s painting. Though the Met has returned works before, no heirs of Mr. Aram have come forward. At the least, the Met would likely provide visitors with a fuller account of its history.

The painting had been retitled by the time the Met purchased it as experts came to believe it depicted not Tarquin and Lucretia, but the rape of Tamar, a daughter of King David, by her half brother Amnon; and that Le Sueur, not Vouet, had painted it.

The tragedy of Lucretia, the virtuous noblewoman who kills herself after being raped by royalty, had been a popular subject for artists and is said to have led to the rebellion that paved the way for the Roman republic.

In the legend, Tarquin threatens to kill her male servant, and place them in bed together as lovers, if she refuses to sleep with him. Among the reasons the Met came to reject the Lucretia description was the gender of the servant in the painting — female, not male as in the legend.

One of the reasons that some experts believe the painting is not a depiction of the Lucretia legend is that it features a female, not male, servant.

Mr. Peter, 53, continues to believe otherwise. A part-time teacher, he is preparing a book on Nazi-looted art and notes the attacker wields a dagger, which is absent from the Tamar story, but typically held by Tarquin.

What is more, he believes the subject of Lucretia spoke to Mr. Aram.

“For Aram the subject had personal meaning since he was facing tyranny himself,” he said. “He had hopes for equal Jewish rights. He could deeply relate to the hope for a rising republic.”

See some of the original German documents:

1933 Sales Contract

After Mr. Aram fled to the U.S., he agreed to sell his Schapbach manor house in southwest Germany and its contents to Oskar Sommer of Trier for 70,000 reichsmarks. The contract specifically excluded, on page 4 of 5, an oil painting (Lukretia). | via State Archives of Baden-Württemberg

Aram Restitution Case

Documents from Mr. Aram’s final attempts at restitution. After his civil lawsuit, he looked to the German state for compensation, pursuing the case over several years. But his case eventually proved unsuccessful. | via State Archives of Baden-Württemberg

Alain Delaquérière and Peter Libbey contributed research to this report.