News:

Family’s battle to recover Nazi-looted art paints auction house into a corner

By Robert Philpot

Vienna-based seller im Kinksy is at the center of a dispute between grandchildren of a couple murdered in the Holocaust and a 2008 buyer whose anonymity it is sworn to maintain

Fritz and Thea Goldschmidt.

LONDON — It is not a multi-million dollar painting that will ever feature in a Hollywood movie. But to Gila DeKay and her brother, Jona Goldschmidt, the Lovis Corinth painting which once hung in their grandparents’ villa in the city of Breslau is “everything.”

The German artist’s 1913 painting “Tirolerin mit Katze” was just one piece of art in a large collection of modern masters owned by entrepreneur and businessman Fritz Goldschmidt and his wife, Thea, which were looted by the Nazis before the couple’s deportation to Theresienstadt and death in Auschwitz.

Lost for decades like the rest of the Goldschmidts’ artwork, the Corinth painting then reappeared in a sale at an Austrian auction house 13 years ago and was sold for 60,000 euros ($70,300).

But Vienna-based auction house im Kinsky continues to refuse to reveal the name of the buyer. Instead, the family was last year offered the chance to buy the painting back for 50,000 euros ($58,580).

“We weren’t about to pay a nickel for something that was stolen,” Goldschmidt, a professor in criminal law at Chicago’s Loyola University, told The Times of Israel.

Goldschmidt, DeKay, their sister, Hanna, and three cousins have no intention of abandoning their fight to recover the painting — the only item from their grandparents’ former collection they have ever come close to tracking down.

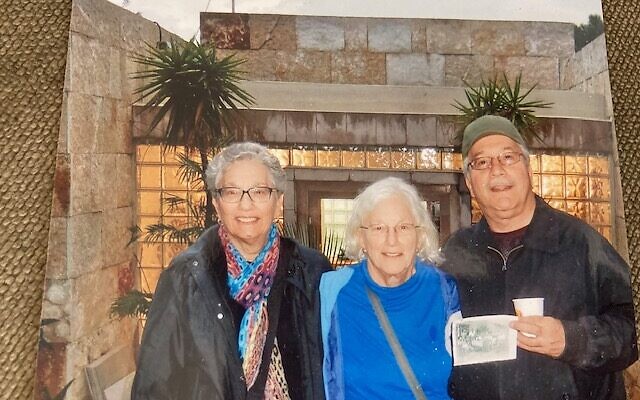

From left to right, Gila DeKay, Hanna, and Jona Goldschmidt are seeking to recover their murdered grandparents’ looted Lovis Corinth painting together with their cousins.

“It’s our heritage and we know our parents struggled to recover this and other paintings. We just want to continue the struggle,” says Goldschmidt. “We don’t want to give it up. I think this painting and our efforts reflect the inability of thousands of descendants of victims of the Holocaust who are trying to get paintings back that are in this second tier of value. We are probably one of a handful of families that are still trying to pursue justice.”

Not a Picasso

Art experts say the case highlights the difficulties faced by families attempting to recover stolen Nazi artwork in some European countries.

“There is very little that we could do right now in Austria that would compel the current possessor to return the painting and even if there was… the cost of doing this would be completely prohibitive, and that’s why this case is a really good representation [of the problems of art of this value],” says Christopher Marinello, CEO and founder of Art Recovery International.

“Everyone loves to write about the Picassos and the Matisses… but they rarely write about these paintings that are worth 60,000 euros. This is the issue — families can’t litigate these cases,” he adds.

The 1913 painting ‘Tirolerin mit Katze’ by German artist Clovis Corinth is the center of a dispute over Nazi-looted art by the original owners’ heirs.

Marinello, who has been working with the family to help restitute the Corinth painting, says that even where the option is available, traveling down a legal path has multiple downsides.

“It’s painful, it’s expensive, it’s time-consuming and the results are uncertain. Every avenue should be taken to resolve these cases outside of the court system, whether it’s through diplomacy or law enforcement,” he says.

Nonetheless, Marinello alleges that his efforts to find an “alternative mediated solution” have been spurned by im Kinsky. There is no suggestion that the auction house knew the Corinth painting was Nazi-looted art. It did not appear on stolen art databases at the time of the sale, although in the Corinth catalogue raisonné, a comprehensive, annotated listing of all the known artworks by an artist, the Goldschmidts are listed as prior owners.

However, Marinello is critical of im Kinsky’s subsequent actions. “When presented with evidence that something is looted that has gone through their saleroom, you would expect a lot more cooperation,” he says.

A modest proposal

Over the past two years, Dr. Ernst Ploil, the chief executive of im Kinsky and an expert in modern art, has floated two proposals on behalf, he says, of the painting’s current “owner” (the Goldschmidt family disputes the use of the term “owner” to describe the possessor of the painting).

The most recent offer, in July 2020, saw the “owner,” according to Ploil, demand 60,000 euros for the Corinth. Im Kinsky, said Ploil, would bear 10,000 euros ($11,700) of this cost, leaving the Goldschmidts to pay 50,000 euros, plus handling and shipping costs.

A previous proposal, made in May 2019, involved the painting being brought back to the auction house and sold off once again. In correspondence seen by The Times of Israel, Ploil said the “owner” of the painting — “a company with residence in Panama” — “is not prepared to restitute the painting unconditionally.” The company had, however, proposed that the painting be sold at a forthcoming auction at im Kinsky — at an estimated sale value of 50,000-100,000 euros ($58,580 – $117,120) with the family receiving 50 percent of the net value of the sale.

“I don’t believe a better result can be achieved,” Ploil wrote. “The owner and his advisors have no experience with looted art and with negotiations concerning paintings once robbed by the Nazi regime.”

Marinello is unimpressed by these proposals. “How insensitive is that to a family that was murdered at Auschwitz and has never recovered a single object that was taken by the Nazis,” he says. “This would be the first one and to tell them that they have to sell it and cannot get restitution is really insensitive of them.”

He believes, moreover, that the auction house represents a potential roadblock to a solution. “We believe that if we could speak directly with the possessor, we would have a different result,” says Marinello.

Christopher Marinello, CEO and founder of Art Recovery International

Ploil, however, defends the offers. In a statement to The Times of Israel he said: “Since I am working both as a lawyer in Austria as well as CEO of the auction house im Kinsky, I have considered the (Austrian) legal situation of the present owner, the auction house and the Goldschmidt heirs very well. The present owner always wanted to stay anonymous and not be involved in disputes. I have done my best to come to a fair and just solution according to the Washington Principles but, as you can see, in vain.”

The Washington Principles, a series of non-binding principles to assist in resolving issues relating to Nazi-confiscated art, were agreed upon following the United States government-led 1998 Washington Conference On Holocaust-Era Assets.

The proposals, Ploil added, have been “the outmost the owner was willing to accept.”

“In my opinion, these proposals have been rather fair and definitely not insulting at all since the present owner has acquired the painting in good faith,” he wrote. “In the last 20 years I have worked on many restitution cases — often representing heirs of murdered victims of the Nazi regime. Many of them have ended with exactly the same result, as I have proposed on behalf of the present owner and the auction house.”

Tragic history

DeKay and her brother, though, find it difficult to talk about the painting in terms of its monetary value. “It’s everything,” she says. “It’s really a memorial to our grandparents.”

“Our grandparents’ story isn’t unique to the upper-middle-class Jewish bourgeoisie in Germany,” DeKay says. “They were people of note. They were dedicated to their community. They were good people.”

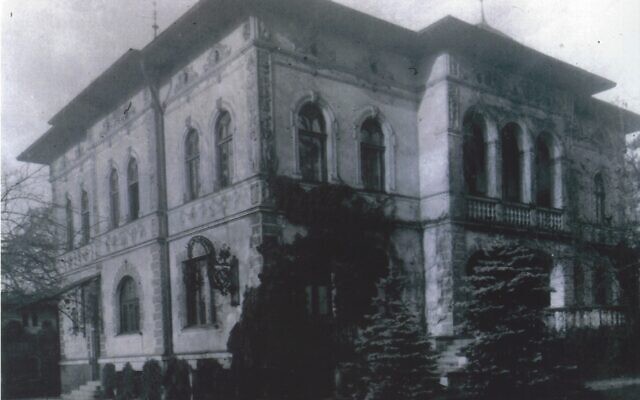

Fritz and Thea Goldschmidt’s Breslau villa.

Indeed, Goldschmidt — who founded one of the leading firms in the German grain business, a realty company and a regional bank — and his wife were highly engaged in the social and cultural life of early 20th-century Breslau (now Wroclaw in Poland). Goldschmidt donated to the construction of a Jewish hospital and helped found a Jewish museum in the city, while Thea led fundraising efforts on behalf of a school for domestic workers.

The couple’s art collection, which also included pieces by Max Liebermann, Max Slevogt, Wilhelm Trubner and Hans Purmann, was housed at their villa, the Villa Kommendeweg, but items were frequently loaned for exhibitions throughout Germany.

Appropriately, their grandchildren have no desire to profit from the Corinth painting. “We don’t want to sell it. We want to have it displayed with the story in memory of our grandparents,” says DeKay.

That story is a painful one. Soon after the Nazis came to power, Goldschmidt was forced to resign the presidency of the bank he had founded. Four years later, the couple had to move from their villa to an apartment. Their sons, Helmut, Gunter and Gebhard, fled Germany for Britain, the US and what was then British Mandate Palestine. As Jewish businesses were Aryanized, Goldschmidt was made to sell his companies. On Kristallnacht, he was briefly detained by the Gestapo. Soon, the couple was required to register their assets with the Nazi authorities. Five thousand marks in gold coins (worth roughly $233,000 in today’s currency) and numerous personal possessions and valuables — including Thea’s jewelry collection — were subsequently seized from them.

While the Goldschmidts managed to get a small number of valuable items and paintings out of Germany with the help of friends who were emigrating, the vast majority of their collection remained in the country — though not in their possession.

The exact fate of the Goldschmidts’ collection is unknown. In 1939, the Nazis identified and targeted Jewish art collections in Breslau for seizure. The Nazis often confiscated assets under the guise of tax liabilities. They also required shipping agencies to report on the storage facilities of Jewish families and stopped the transfer of works of art. Some Jewish collectors were forced to sell off items at a fraction of their true value, with unscrupulous middlemen and dealers reselling them for an inflated profit.

What is clear, however, is that by 1940, when they were forced to move again to an even smaller apartment, the Goldschmidts had lost much of their collection and assets.

In 1943, a postcard from Thea to a cousin revealed the couple was about to be transferred to Theresienstadt and that they would only be allowed to take what they could carry with them. It also indicated that they had already been forced to sell off their art and personal library for virtually nothing in order to survive.

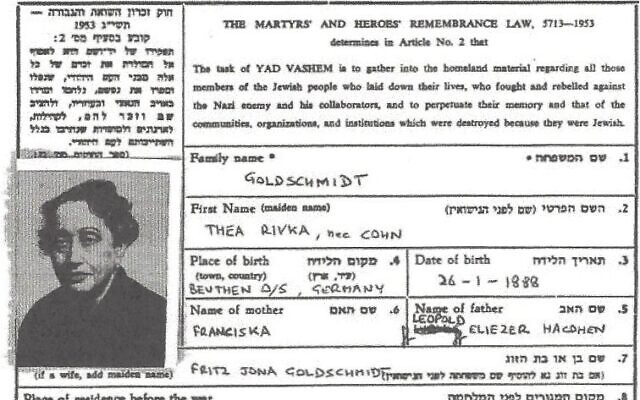

Image of Thea Goldschmidt from the Yad Vashem archives

Subsequent postcards Thea sent from Theresienstadt prior to their deportation to Auschwitz suggested that anything they still owned had been left behind in the apartment. A non-Jewish acquaintance of the couple stated that the Nazis had taken what had remained and that the building was found empty.

Mysterious disappearance — and reappearance

The Corinth painting was not among the handful of the Goldschmidts’ paintings taken out of Germany before the war and remained with the couple until they were either forced to sell it off cheaply or it was confiscated by the Nazis.

“We don’t know at what point that particular painting left the collection. We do know it was either a forced sale or it was looted,” says Carrie Laverick, founder and president of art appraisal and consultation firm Veritas, who has been working with the Goldschmidt family on the case for a decade.

Carrie Laverick has been working with the Goldschmidt family on getting the Corinth painting back for a decade

The distinction, she adds, is immaterial regardless. “It doesn’t matter. The research that we have done, and we have firsthand letters and accounts and we also have data, shows consistently that Fritz and Thea were being forced out of their homes, forced to downsize, forced to sell everything they had. So it’s obvious they were having to get rid of their art collection, little by little, unwillingly,” Laverick says.

The Goldschmidts’ sons began their ultimately fruitless effort to recover, or receive compensation for, their dead parents’ looted art collection in 1956. Letters between the brothers as they sought to compile a list of lost and confiscated assets refer to the Corinth painting as missing, and it is contained in an inventory supplied by them to the Wiedergutmachungsämter, the German agency handling restitution claims, in 1957.

Four years later, the family became aware that the painting had been sold in 1957 at the Lempertz auction house in Cologne. But, when approached as to who had sold and bought the Corinth, the then-director said the family would have to sue in order to obtain that information.

Subsequent research by Laverick revealed that the painting, in fact, first reappeared after the war at Bremen’s Graphic Arts Cabinet in 1950. In addition to the 1957 sale, it was offered for sale in Berlin in 2004 and sold again by the Lempertz auction house in Cologne in 2006. But it was not until a decade ago that the Goldschmidt family discovered about the painting’s sale by im Kinsky in 2008.

“We were furious. We just were appalled,” says DeKay, recalling their reaction to the news of the sale.

For now, says her brother, the family has one comfort: the knowledge that the painting cannot be resold.

“We are comforted but the fact that so long as this matter is unresolved, the painting will never be able to be sold openly, exhibited or exported in any manner,” says Goldschmidt. “If the current owner, his heirs or assignees attempt to sell it, they will be knowingly transferring a painting subject to a bona fide claim of Nazi-era possession and the purchaser in turn will not be able to defend the sale as one made in good faith.”