News:

From Nazi Looting to the Museo de Pontevedra

By Patricia Fernândez Lorenzo

(Spanish and English published version below)

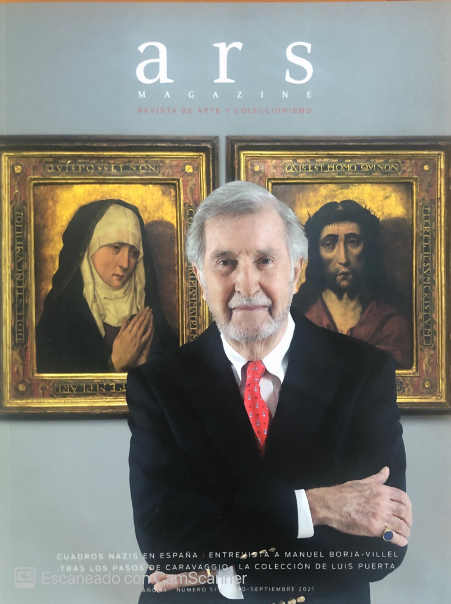

Prince Adam Karol Czartoryski at the Museum of Pontevedra in front of the diptych

THE MUSEO DE PONTEVEDRA’S Flemish diptych attributed to Dieric Bouts, depicting the Mater Dolorosa and Ecce Homo, has been identified as one of the works from Goluchów castle’s prestigious Czartoryski collection, plundered by the Nazi regime during their occupation of Poland. Adam Karol Czartoryski has visited the Galician museum to see for himself the family heritage being claimed by the heirs.

«We’ve spent decades trying to retrieve works of art from the family collections that were looted by the Nazis. In all these years, we’ve barely recovered a dozen pieces from various museums, but there are hundreds of items whose whereabouts are still unknown».

While uttering these words, Prince Adam Karol Czartoryski’s eyes are drawn to the diptych that adorned the walls of Goluchów castle until 1939, when the Nazi army’s invasion of Poland forced his grandmother to pack up the most valuable objects and conceal them from the pillaging ordered by Hitler. That same year, his parents, Augustyn Czartoryski and Maria Dolores of Bourbon-Two Sicilies, left the country, headed for exile in Seville, «where I was born», he adds.

Eighty years have had to go by in order to be able to undertake that long-awaited face-to-face: «We knew the first part of the story of the diptych, which ended abruptly in 1944 with its disappearance. Now we know what its destination was; all we need now is a fair denouement».

The Czartoryski family are not the first, nor will they be the last, victims of the greatest art pillage in European history to demand the restoration of “Nazi-looted art”, as such ransacked works are termed in international art jargon. The steady drip-drip of news regarding new cases is ongoing in Europe and the US, the fruit of the international consensus reached with the signing of the Washington Principles (1998) and the subsequent Declarations of Vilnius, Lithuania (2000) and Terezin, Czech Republic (2009), by which the signatory nations (such as Spain) commit to restoring items to their legitimate owners, whether the victims themselves or their heirs, as long as they have been identified.

The genealogy of the Czartoryski collections is closely interlinked with the political and cultural history of Poland. In 1796, Princess Izabela Czartoryska (1746-1838) sowed the seed by opening the first Czartoryski Museum at her residence in Pulawy, amassing both antiques and a considerable number of paintings. These included Leonardo da Vinci’s Lady with an Ermine and a Portrait of a Young Man, by Raffaello Sanzio, purchased in Italy in 1798 and sent to Poland in 1801 by her son, Prince Adam Jerzy Czartoryski (1). Although the Da Vinci was recovered by the “Monuments Men”, the Raphael portrait continues to be the great lost jewel from the family collection. Forced into exile in Paris, following their political activism in the failed Polish uprising against Russian occupation in 1830, his children, Wladyslaw and Izabella, took up the baton from their grandmother. Drawn to the art-collecting vogue inspired by France, they purchased exquisite pieces, building up a collection that was admired by their contemporaries, and which could be visited at the family’s Paris residence, the iconic Hotel Lambert.

In 1855, Prince Wladyslaw Czartoryski (1828-1894), leader of the family, took a Spanish wife, María Amparo de Muñoz y Borbón, the Countess of Vista Alegre (2), and maintained close relations with the Spanish royal family, as is shown by the copious surviving correspondence preserved in the National Historical Archives. His sister, Princess Izabella (1830-1899) married Count Jan Dzialynski, and was thereafter known as Izabella Dzialynski.

When the time came for them to consider a return to Poland, the siblings had to divide up the collection. Izabella chose a series of Greek and Etruscan antique pieces, and a carefully-selected ensemble of Medieval art, which she had moved to her residence in Goluchów castle, where she opened a museum. Her brother Wladyslaw, who received the main nucleus of the family collection, opened the Czartoryski Museum in Krakow in 1878. Two collections, and two museums devoted to enriching the cultural life of the nation.

The impressive Goluchów castle, which today serves as the headquarters of a branch of the National Museum in Poznan ́, stands in the midst of leafy grounds measuring several hectares. Of medieval origin, the building was renovated in the historicist spirit of the 19th century, drawing on the style of castles in the Loire. The magnificent collection amassed there was made up of more than 5,000 decorative art objects, along with several hundred paintings of great value, including the Mater Dolorosa and Ecce Homo diptych, identified as a Roger van der Weyden replica, as noted in the first visitors’ guide published in 1913 (3). The guide published in 1929 also attributed the diptych to the same artist (4), and the fact is that it was not until the 1940s that authorship of the work was attributed to the Dutch painter Dieric Bouts (1415-1475).

The diptych shared wall space with works by Jan Brueghel, Hans Memling, Jean Clouet, Luis de Morales and Esteban March – from the Spanish school – A. Carracci, 17th-century portraits from the Flemish, German and Polish schools, and even some noteworthy copies, such as that of the portrait of the Infanta Maria Anna by Velázquez (5). All of these were arranged in rooms that were lavishly decorated with sculptures and display cabinets bursting with delicate artistic objects.

In June 1939, as war loomed large, and with Prince Adam Ludwik Czartoryski, the owner of the castle, having died in 1937, his widow decided to remove the most valuable items and transport them to Warsaw, concealing them in 18 boxes behind a wall of the house’s wine cellar. However, the pressure exerted by the Nazi officials was sufficient to convince her to reveal their location. This level of coercion applied in locating artistic treasures was widespread, and the transcripts of the Nuremberg Trials do not spare any detail when highlighting Göring’s vast, systematic and organised plan to culturally impoverish Poland, in which the looting of the Goluchów castle collection features prominently (6).

Items were confiscated and moved to the National Museum of Warsaw in December 1941, where they were inventoried and photographed. These records have proved key to identifying the diptych, which for many years was recorded as lost both in the database of objects looted in Poland, managed by the country’s Ministry of Culture and National Heritage, titled “Wartime Losses” (7), as well as in the book addressing the same subject, and published in 2000 (8).

Faced with the imminent demise of Hitler’s regime, some of the pieces were taken to Austria, while others were pillaged by deserters and refugees as they fled, and sold to art dealers, which is where we lose track of them. As such, the why and wherefore behind the diptych’s arrival in Spain is somewhat nebulous. The first clue is to be found in the excellent study carried out by Elisa Bermejo Martínez on the Flemish Primitives, which includes an exhaustive review of Mater Dolorosas and Ecce Homos attributed to the artist, to his son Albert Bouts and to his workshop. Along with works from the Weissberger collection, the Balanzó collection, that of the Duke of Bailén or the Royal Chapel in Granada, the author identifies the diptych in question, referring to its provenance as «conde Czartoryski de Polonia» in «Madrid 1973. Comercio de arte» (9). The database of Belgium’s Royal Institute of Cultural Heritage provides one further detail by identifying it in the «Establecimientos Maragall S.A.» (10), which leaves no doubt that the collector José Fernández López must have purchased it on the Spanish art market prior to selling it on, along with his entire collection, to the Museo de Pontevedra in 1994.

As was the case with other countries, Spain was a place of refuge and a point of transit for art dealers introducing Nazi-looted works onto the market (11). However, there have been relatively few claims made on public Spanish museums. One of the most recent was the one lodged by Paul Cassirer, grandson of Lilly Cassirer, against the Thyssen-Bornemisza Foundation regarding the painting Rue St. Honoré, Afternoon, Rain Effect, by Camille Pissarro, purchased by Baron Thyssen in New York in 1976 and sold to the Foundation, along with the rest of his collection, in 1993. The lengthy and complex legal trial, which had been going through the courts of California since 2005, finally granted ownership to the Foundation, although it also issued a call to the Spanish authorities to ensure the country complies with the international commitments to restoring works of art to victims and their heirs (12). In closer compliance with said commitments was the solution reached for The Family in a State of Metamorphosis, by the Surrealist painter André Masson, confiscated from the banker Pierre David-Weill’s Paris residence in 1940. The painting joined the Museo Reina Sofía’s collections in 1995, with the museum recognising the heirs’ legitimate claim to the work and a financial arrangement with the family being reached by which the painting could remain at the museum.

It seems somewhat anomalous in the case we have before us here that the Polish Ministry of Culture (without either the representation or consent of the heirs) should have undertaken to submit a claim with the Spanish authorities which, de iure, corresponds to the family. It is as such that Prince Adam Karol Czartoryski concludes: «These works of art underwent so many vicissitudes, and such have been the efforts of our ancestors to avoid their looting throughout the tumultuous military history of the country, that our responsibility (I refer to both mine and that of my cousins, the Counts Zdzislaw, Maria Helena and Adam Zamoyski) is to continue to walk the path first embarked on two centuries ago, and demand their return to the family».

Notes:

1. ZAMOYSKI, Adam. The Czartoryski Museum. Poland: Princes Czartoryski Foundation, p.33].

2. Maria Amparo de Muñoz y Borbón (1834-1864), fruit of the morganatic marriage between the Queen Regent Maria Christina of Bourbon-Two Sicilies and Agustín Muñoz, Duke of Riánsares, died young, and her son Agustín became a Catholic priest, and therefore did not have any children. Wladyslaw Czartoryski subsequently married Princess Marguerite of Orléans, and that union led to the birth of a son, Adam Ludwik Czartoryski, grandfather of the current heirs to the collection.

3. Przewodnik po muzeum w Gołuchowie [Gołuchów Museum Guide]. Pozna n ,1913, p.42.

4. Przewodnik po muzeum w Gołuchowie [Gołuchów Museum Guide]. Pozna n, 1929, p.44.

5. ESTREICHER, Karol. Cultural losses of Poland during the German occupation, 1939-1944. London: 1944 [republished in 2003, Krakow: Society of the Friends of Fine Arts, pp. 169].

6. Trial of the Major War Criminals before the International Military Tribunal. Nuremberg, Vol. IV. Proceedings 17/12/1945 – 8/1/1946, pp. 66-99.

7. Image 38234. Recovered in http://lootedart.gov.pl Consulted: 1/05/2021.

8. Wartime Losses. Foreign Paintings. Vol. 1. Poland: Polish Ministry of Culture and National Heritage, 2000, pp. 108-109.

9. BERMEJO, Elisa. La pintura de los primitivos flamencos en España, II. Madrid: Instituto Diego Velázquez, CSIC, 1982, p. 36.

10. Christ crowned with thorns, object 40002863, image 107; Mater Dolorosa, object 40002864, image 108. Recovered in http://balat.kikirpa.be Consulted: 1/05/2021.

11. MARTORELL, Miguel. El expolio nazi. Barcelona: Galaxia Gutemberg, 2000.

12. MATEU DE ROS, Rafael. «Comentario de la Sentencia del Tribunal del Distrito Central de California de 30 de abril de 2019: caso Cassirer vs. Fundación Colección Thyssen-Bornemisza». Patrimonio cultural y derecho, no. 23, 2019, pp. 559-5

To read the article as published in Spanish and English see the PDF here.