News:

'What the Nazis Stole from Richard Neumann (and the search to get it back)' opening at WAM

By Richard Duckett

WORCESTER — Beginning around the early years of the 20th century and continuing up until around 1938, Dr. Richard Neumann built a notable collection of more than 200 paintings and sculptures that included Italian Renaissance art and Old Masters.

Giovanni Battista Pittoni, the younger (Italian, 1687–1767), Hannibal Swearing Revenge against the Romans

"You could tell he had a really refined taste," said Claire Whitner, the Worcester Art Museum's Curatorial Director and James A. Welu Director of European Art.

However, "When you're talking about works of art from a person's collection, the through line is the person," Whitner said.

Richard Neumann (1879-1959) was a remarkable person and the joys and sorrows of the through line of his life are captured in the Worcester Art Museum's latest exhibition, "What the Nazis Stole from Richard Neumann (and the search to get it back)," opening April 10 and running until Jan. 16, 2022. (Currently, admission to WAM galleries and shop is by timed entry and advance ticket only. Visit worcesterart.org)

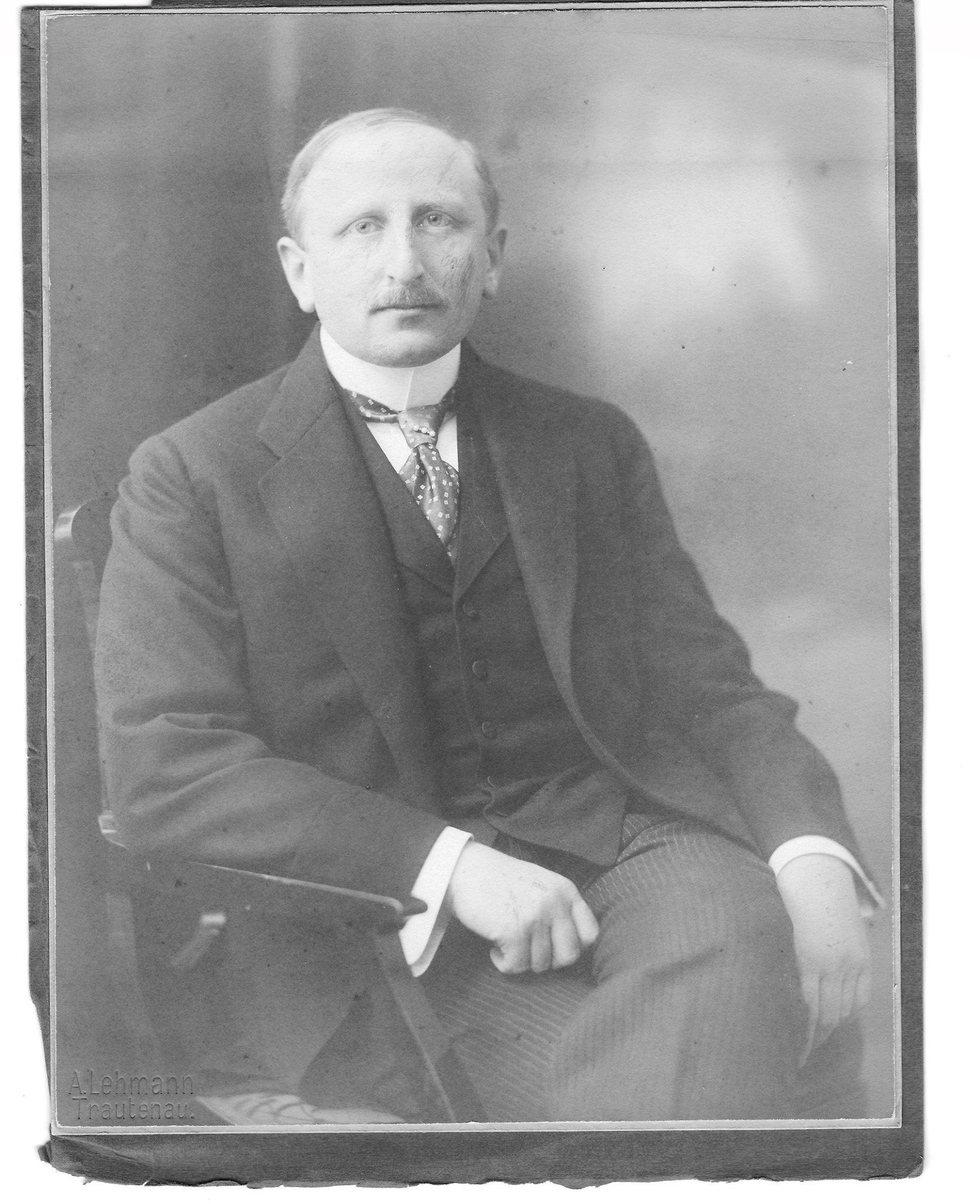

Richard Neumann before World War ll.

The through line continues on from 1938, when Neumann, an Austrian businessman of Jewish heritage, had much of his art collection seized by the Nazis following the annexation of Austria that year by Nazi Germany.

Neumann and his wife, Alice, fled from Vienna to Paris, taking with them some 38 pieces from their collection. They lived in Paris for a while after the Nazi invasion of France, and then in 1942 managed to escape to the unoccupied zone and eventually to Cuba.

But Neumann lost the remaining works of art in his possession. In Cuba, he initially worked as a foreman in a textile factory. He and his wife finally moved to New York City, where Neumann died in 1959.

Neumann spent the final years of his life trying to get his art collection back, an extremely difficult task but one his family has continued to this day. The quest is not only for the family's personal satisfaction, but also following the wishes of Neumann "who believed in the obligation to promote the role of the arts in civic life,” Whitner said.

To date, some 16 pieces have been returned to the family, of which 14 are in the "What the Nazis Stole from Richard Neumann" exhibition.

These works have been placed with Worcester Art Museum by Neumann's family on long-term loan.

Maerten van Heemskerck (Netherlandish, 1498–1574), Right Altar Wing with Female Donor, about 1540, oil on panel, The Selldorff Family in memory of Richard Neumann.

Among them are the left and right wings of a 16th-century triptych by the Dutch painter Maerten van Heemskerck, and two sculptures by high-Baroque sculptor Alessandro Algardi and Rococo period sculptor Guiseppe Sanmartino. Also included are works by Italian Renaissance artists Alessandro Magnasco, Giovanni Battista Pittoni the Younger, and Alessandro Longhi.

After the exhibition closes in January 2022, the loans will be integrated into WAM’s existing Old Master collection galleries.

Tom Selldorff, Richard Neumann's grandson, who lives in the Boston area, said, "WAM is a highly regarded museum in the area of course, and in fact we had contact with them several years ago through a former chairman of their Board of Trustees, Cliff Schorer.

"And we knew of their extensive collection of Renaissance art. When we needed to find a home for our recovered art collection because of moving to a retirement home, it was Claire Whitmer who really took an interest and we found a lot of common ground. That was why we decided that WAM was the best place to house my grandfather’s art, a place where both our family and the general public could enjoy it."

Added Whitner: "While his family’s struggle for the restitution of his collection is all too emblematic of the challenges faced by many other Jewish collectors of that period, we are tremendously grateful to his family for their generosity in committing to this long-term loan of these works, which will make it possible for a new generation of audiences to admire them, as well as for us to conduct new research and scholarship.”

In addition to the art, "The What the Nazis Stole from Richard Neumann" exhibition has several interesting features such as a recreation of Neumann's home in Vienna just before the infamous Anschluss, March 12, 1938, and a timeline of his family’s efforts to reclaim the art works over the last 75 years.

Maerten van Heemskerck (Netherlandish, 1498–1574), Left Altar Wing with Male Donor, about 1540, oil on panel, The Selldorff Family in memory of Richard Neumann.

Whitner, who is also the exhibition's curator, said she considered "what is a way that we can tell the story in a compelling manner?"

To that end, a space has been created that evokes what a family parlor in Vienna of this period might have looked like. A floor-to-ceiling reproduction has been created, made from a photograph of the family's Vienna home. Period-appropriate seating will also be included, so that visitors can view part of the collection from the vantage point they would have had as guests at the Neumann home.

There will also be books in this parlor seating area that relate to the topic of Nazi-era provenance and restitution claims, underscoring the challenges that many families have faced since the end of World War II.

People will see the artworks in the context of "the last time they were all together in his home," Whitner said.

"You get a sense that you're in a private home sitting in Neumann's parlor, and I think that's a critical piece of the story to think of that domestic space where all the paintings were together for the last time," she said. It was a home that "ceased to be rather quickly."

Sebastiano Ricci (Italian, 1659–1734), Abraham and the Three Angels, about 1695, oil on canvas, The Selldorff Family in memory of Richard Neumann.

Neumann was born in Vienna to a well-to-do family of textile manufacturers, and was both president of his family’s company — which had mills throughout Austria and Bohemia — and a lover of the arts who earned his Ph.D. at the University of Heidelberg. By the age of 42 he had assembled a grouping of works of such quality that 28 of the pieces were given the status of Viennese “landmarks” in 1921.

Neumann had the art works in his home, "but he also lent them liberally to exhibitions," Whitner said.

"He definitely saw an importance of having his collection seen beyond his own home. He was not buying and selling to make money, he was buying to create a collection and keep it whole," she said.

Following Nazi Germany's annexation of Austria in 1938, Neumann's collection was inventoried in accordance with anti-Jewish laws put in place by the Nazis, and most of it was seized through a series of forced sales and the denial of requests for export licenses.

Many of the works were destined for display in an art gallery that Adolf Hitler wanted to build in Linz, the Austrian city in which he grew up. The gallery was to have been filled with artworks looted across Europe by the Nazis from museums and private collections, many of them Jewish.

Two of the paintings in the "What the Nazis Stole from Richard Neumann" exhibition will be placed on pedestals so that people can see how backs of frames were stamped by various officials or people who came into possession of the works.

Alessandro Algardi (Italian, 1598–1654), Pope Innocent X (bozzetto), about 1640s, terracotta, The Selldorff Family in memory of Richard Neumann.

Neumann had begun filing lawsuits against the Austrian government in the 1950s but international rules and regulations were not initially helpful to people in his position.

"The laws of the land won't allow him to get his hands on paintings. It gets very complex. It's a process. It's been an incredible amount of work," Whitner said.

Selldorff began working with the Vienna-based art historian, Sophie Lillie, who is also an adviser to the "What Nazis Stole from Richard Neumann" exhibition.

Lillie documented some 50 of the stolen works in her book “Was einmal war” (“what once was”) based on inventories of artworks recovered by the “Museum Men” at the end of the Second World War.

She helped the Neumann family recover two objects from the Weinstadtmuseum in Krems, an Austrian town, six from Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum, and six from French museums, including the Louvre in Paris.

Two paintings, which resurfaced on the art market in recent years, were recovered from private collectors.

“My grandfather had a deep love and understanding of timeless fine art, and of its importance to a civilized society,” Selldorff said. "It’s been a privilege to work on recovering some of his collection and to pass his passion on to our children and grandchildren.”

Still, there are many works that have not yet been tracked down and the 14 pieces at the WAM exhibition are a fraction of what Neumann once owned.

Through it all, "art is the thing that sustains," Whitner observed.

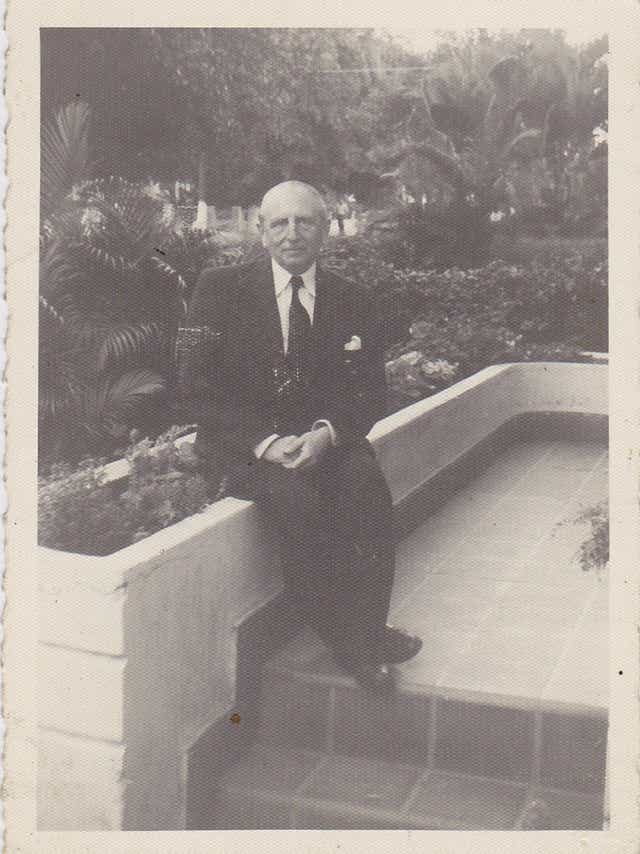

An undated photo of Richard Neumann in Havana

When Neumann was in Cuba working as a foreman in a textile factory by day, he was lecturing on art in the evenings. He was also trying to get a fine art museum built there — Havana’s Palacio de Belles Artes, Whitner said.

"This (art) really is his avocation," she said. "He had a real love of humanity, and I think art encapsulates that.

"War destroys, art creates. And to pass that along — the way the surviving family members have approached this is really inspiring. With tenacity, but trust in the real good of humanity in spite of everything."