News:

Dutch Railroad Reckons With Holocaust Shame, 70 Years Later

By Nina Siegal

Jews entering Westerbork, a transit camp in the northeastern Netherlands, in 1942. The Dutch national railroad deported about 107,000 Jews to Nazi camps. Only 5,100 survived.

Jews entering Westerbork, a transit camp in the northeastern Netherlands, in 1942. The Dutch national railroad deported about 107,000 Jews to Nazi camps. Only 5,100 survived.

AMSTERDAM — The indispensable role that German railroads played as part of the Nazi machinery of genocide during World War II has long been known. But it may be only now that the Dutch are beginning to fully reckon with the role that their own national railroad played in the Holocaust.

For several decades, according to the historian David Barnouw, many Dutch people regarded the wartime performance of their railway system, the Nederlandse Spoorwegen, or N.S., as heroic. In September 1944, the Dutch government in exile in London ordered the railway workers to strike, which they did for almost eight months until the end of the war.

This strike, however, came after the Dutch national railroad had already deported some 107,000 Jewish residents of the Netherlands — of 140,000 people who identified as Jewish in 1941 — to transit and extermination camps such as Sobibor, Bergen-Belsen and Auschwitz, on commission from the German occupying forces. Only 5,100 survived. In addition, thousands of Sinti and Roma people, as well as gay men and lesbians, disabled people, and resistance fighters were also transported to camps on Dutch railroads.

That much is now widely known in the Netherlands, as is the notorious praise that Adolf Eichmann, the Nazi official who drew up plans for deportations and genocide, once offered the Dutch national railroad: “The transports run so smoothly that it is a pleasure to see.”

But new research, published in a Dutch book that was released on Sept. 17, to coincide with the 75th anniversary of the Dutch railway strike, indicates that there were more transports than previously thought, and that the Dutch national railway set up special services to facilitate the German-run deportations.

The book, “De Nederlandse Spoorwegen in oorlogstijd 1939-1945,” (“The Dutch Railroad in Wartime, 1939-1945”) attempts to clarify the role of the railroad under German occupation, and to offer a comprehensive accounting of the trains and their impact.

“We wanted to be as strictly correct as possible so we know the right numbers,” said Guus Veenendaal, one of the three authors. “There are so many false rumors, and there are numbers with no foundation at all. For us, it was especially important to establish a complete set of figures.”

In all, the researchers found, 112 Dutch trains went from the Netherlands to nine German Nazi camps in countries such as Germany, Austria and Poland from June 1942 to August 1944.

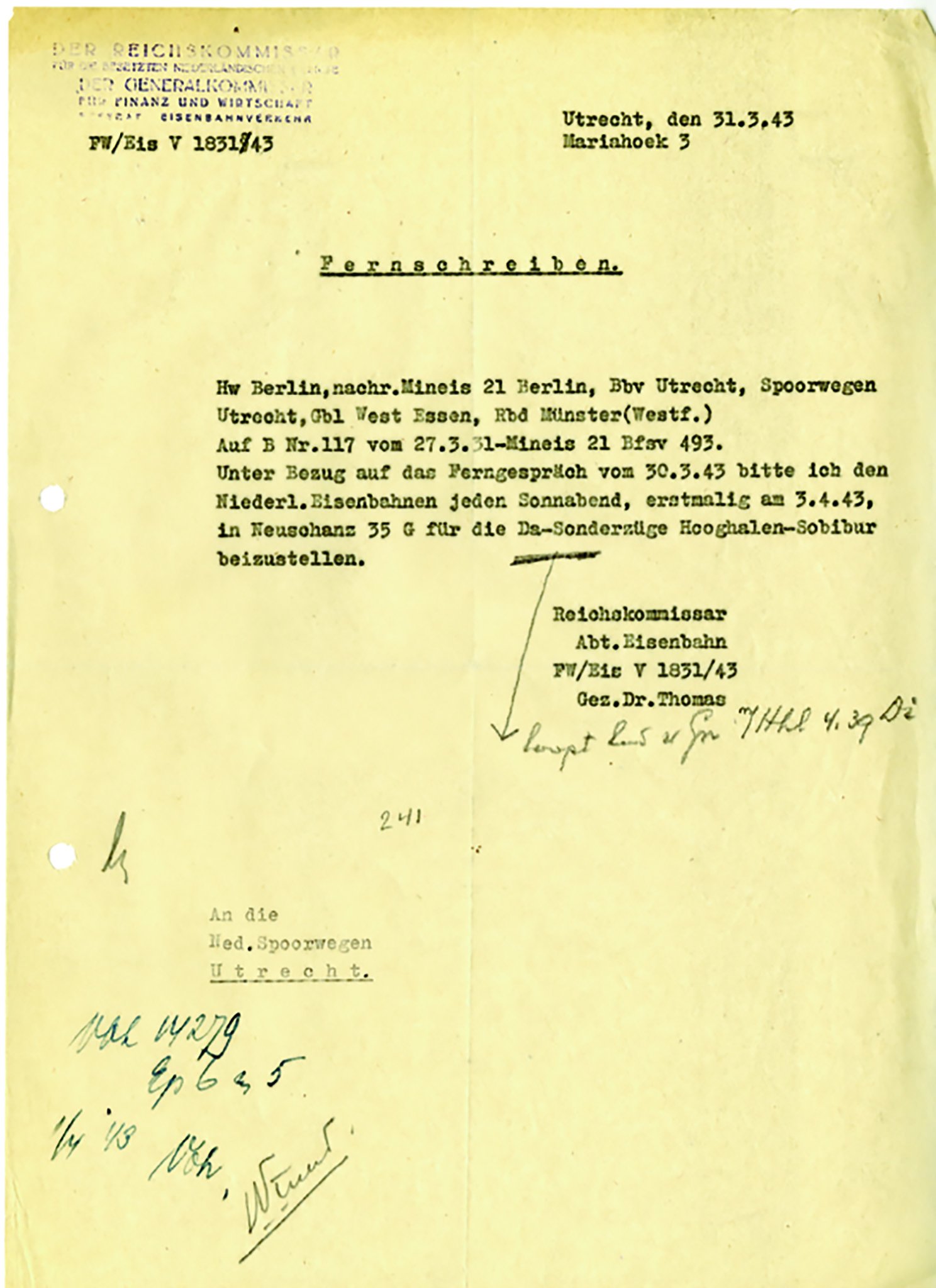

A German order to Dutch railroad officials commissioning trains to the Sobibor death camp.CreditDutch Railway Museum

Each train that left the main transit camp, Westerbork, carried an average of about 1,000 people, with some trains taking as many as a few thousand Jews at a time to the death camps.

The Dutch national railroad invoiced the Germans about the equivalent of 3 million euros, adjusted for inflation, for running these trains, according to Dirk Mulder, one of the authors. The Germans may not have paid this full amount, about $3.28 million, but no one knows for sure, because the records have been lost.

The Germans paid one small amount per person to transport someone first from Amsterdam (where the Jewish population had been forced to relocate) to the transit camp at Westerbork, about a 3.5-hour ride by train. From there, the Germans paid an additional few cents a person for the ride to the Dutch-German border at Nieuweschans.

At the border, the Dutch conductor and crew were replaced with a German crew, said Mr. Barnouw, so it remained an open question as to how much the Dutch train officials knew was going to happen to their passengers.

“You cannot say that N.S. knew more than other people,” Mr. Barnouw said in an interview.

But Mr. Veenendaal disagreed. “Later in the war, the railway people knew exactly what was going to happen, in 1944,” he said. “I don’t know if they knew earlier. Maybe they didn’t want to know.”

The report does not go into great depth about this question, and as a result, members of Jewish organizations feel the research is inadequate.

“The railways in the Netherlands were the instrumentality that enabled the death of thousands during the Holocaust,” Gideon Taylor, chair of operations for the World Jewish Restitution Organization, said in an email. “Recognition of what happened is important, not only for those who survived, but also to educate future generations.” He added, “The research published so far is limited and partial.”

The researchers located the only known telegram from the German authorities instructing the Dutch railways to prepare trains for transport of Jews from Westerbork. The rest of the documents were probably burned in a fire set by the German authorities near the end of the war, Mr. Veenendaal said.

In 2005, the Dutch national railroad officially acknowledged that it had collaborated with the Nazi occupiers and apologized for its role, and the company announced last year that it would allocate about 50 million euros, or about $55 million, to compensate survivors and their next of kin.

It appointed an independent committee to devise a payment plan, or what it terms as “individual moral gesture,” and opened its archives to researchers. The amounts of the payouts, from €5,000 to €15,000 (or about $5,500 to $16,400), were announced in June. Westerbork’s camp commander making a final check before a train departure in 1944. Credit Herinnerings-centrum Kamp Westerbork

Westerbork’s camp commander making a final check before a train departure in 1944. Credit Herinnerings-centrum Kamp Westerbork

So far, 4,500 applications have been filed, according to a spokesman for the state-owned railroad company.

Roger van Boxtel, the chief executive of the railroad, said that the money was intended as a gesture, but that he recognized that “it is just a small Band-Aid on a big wound.”

“It has been a really emotional experience for a lot of people,” said Flory Neter, who runs a volunteer foundation that helps survivors and their relatives apply for compensation. “The trains were really the end. Yesterday I got on the phone at 10:30 a.m. and I talked for hours straight to people trying to fill out these forms, trying to comfort them and give them perspective.”

Eduard Neter, Flory’s husband, was born in 1939. Both of his parents and his sister were deported on Dutch trains to Auschwitz, where they all died. He was able to apply for compensation for each of his parents, but not for his sister — because the compensation criteria do not include grandchildren or siblings of those murdered.

Other relatives of victims felt that these criteria were too limited. On Sept. 1, a few hundred people met with members of the independent committee to air grievances.

No Dutch railroad officials attended that meeting, and Mr. van Boxtel said that the compensation plan was unlikely to change at this point.

It is still hard to understand why the Dutch railway transports ran “so smoothly,” but the researchers say that it was because the railroad had a rigid, hierarchical structure, the employees were dutiful, and German reprisals for insubordination would have been harsh.

Ms. Neter said this aspect of the railway’s role has still not been fully examined. Deeper research, she said, would be “needed to get a clear view on these painful and almost unrevealed aspects of the Holocaust.”

Mr. Veenendaal said that the researchers found no evidence of active sabotage on the part of railroad officials, managers or employees who facilitated the Jewish transports at the time.

“There is one engineer, a machinist, who refused to drive one of the trains with Jews on it,” he said. “He was simply replaced by another machinist, and he was listed as being sick and unable to do his duty. That’s all; only one. The rest of them did their duty, and they ran the trains.”