News:

We're done with the war

By Vladimir Medinsky

Russian original text via the link below

Guide English translation:

On new attempts to revise the outcome of the Second World War through restitution

At the end of December 2018, the German embassy spread information that it intends to seek the return to its country of cultural property, which as a result of the Second World War moved from Germany to the USSR. Then the diplomats quickly recovered: they say, we are not seeking a decisive return, but we want to intensify negotiations on this topic.

Soviet soldiers inspect the exhibits of the Goethe house-museum in liberated Weimar, Germany.

However, even this supposedly streamlined, but quite official statement requires a comment. And the explanation: why this will not happen - no "return", not even any substantive "negotiations" about something like that.

The current state of affairs is historically just, it corresponds to the norms of international and Russian law and, most importantly, the norms of morality and ethics and does not need to be revised. What the Soviet Union sought from Germany after World War II is documented and rightfully belongs to us: firstly, as a country that suffered from perfidious aggression and barbaric methods of warfare by the Nazis; secondly, as compensation for damage caused during the war years, including plundered and illegally exported cultural property, and, finally, as the victorious power.

The cultural treasures transferred as compensatory restitution from the territory of Germany are the property of the Russian Federation. These treasures today remain the property of world culture. But only the Russian state as an owner has the right to dispose of them.

Background and the letter of the law

To begin with let us define our terms. German colleagues use the word "restitution" in the sense of "return to the owner." Because the treasures transferred to the USSR are supposedly "trophies".

However, this is not true either historically or legally.

Before World War II, a simple principle operated regarding the cultural treasures of the warring countries: the winner gets everything he can reach.

So, in fact, national museum treasuries and many private collections of mighty military powers — Britain, France, Germany, and partly the Russian Empire — grew, which must be concealed.

The first attempts to regulate the attitude to cultural treasures during wars were undertaken within the framework of the Hague Conventions of 1907. The belligerents were called "as far as possible" not to destroy "temples, buildings serving the purposes of science, the arts, historical monuments."

Alas, the declarations and declarations remained so, no one listened to them. Already in the first weeks of the First World War, the Germans erased the famous Rheims Cathedral in France. In the occupied territory of the Russian Empire it went as far as melting down monuments to obtain metal "needed by the German army."

And only on the basis of the Second World "right of the strong" for the first time was it attempted to somehow drive a new principle into the framework of international law. At this time, it was not the spiritually indifferent humanists who made the case, but the victorious powers themselves.

The scale of the robbery by the fascists on the occupied territories of the USSR and Eastern Europe was unprecedented. To punish the Nazis, it was necessary to create a special legal framework. It began to be formed by the powers of the Anti-Hitler Coalition as early as 1943. The so-called London Declaration declared all seizures of property in the territories occupied by Germany and its allies to be invalid, and as a result of the Yalta Conference (February 1945) a special reparation commission was created to develop a legal framework and mechanisms for resolving two issues:

- firstly, the restitution of property exported by the Nazis from the countries affected by the aggression - the return of the stolen, to put it simply;

- secondly, so-called. compensatory restitution, i.e. compensation of valuables, irretrievably lost, destroyed.

This Inter-Alliance Commission approved in 1946 the “Four-Party Restitution Procedure,” which emphasized: “... Property of a unique nature, the restitution of which is impossible ... can be replaced with equivalent objects.” It is on this document, as well as the decisions of the Nuremberg Tribunal, that the right of Russia (as well as France, countries of Eastern Europe, Greece, Benelux states, Scandinavia) relies in regard to the so-called. "displaced values".

From the RSFSR, 1,177,291 artworks were stolen,13,000 musical instruments, 180 million books, 17 million archival files; 3 thousand monuments destroyed

I emphasize: there was no "robbery" of the defeated Germany, there were no "war trophies" - there was a strictly regulated return of the loot and the equivalent compensation of what had been lost and destroyed. So "restitution" (if we take this term) in relation to Russia, which for some reason German colleagues are talking about, has already taken place.

By law and justice

Do these norms still apply? Yes, they do.

Soviet soldiers with the abandoned treasures of Peterhof and Tsarskoye Selo after the retreat of the Germans

The later international legal regulation of the topic of “displaced cultural property” in relation to future military conflicts took place in the 1950s–1970s. ('The Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict', The Hague 1954, and the UNESCO Convention of 1970 'On Measures to Ban and Prevent the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property'). These acts expressly prohibit the viewing of cultural property as war booty. They are usually referred to in the West as an argument in favor of “return”, although everyone understands that these references are legally ridiculous. For:

1) these acts are not retroactive;

2) they are fully consistent with the spirit of the Allied decisions of the 1940s;

3) on top of everything - there is also an UNJUSTIFIABLE legal document - 107th Art. UN Charter on the inadmissibility of a review of the outcome of the Second World War.

This is about the legal side. I think it’s unnecessary to talk about the moral side of such demands.

It is curious that before the collapse of the USSR, Germany itself never doubted the legality of the export of art objects to the victorious powers. In 1990, during the negotiations on the unification of Germany, the governments of the Federal Republic of Germany and the GDR even made a special joint statement: "The measures to seize property taken on the basis of the rights and supremacy of the occupation authorities (1945-1949) are irreversible."

The arithmetic of the law

Now a little history. The Nazis plundered and destroyed Soviet culture systemically. It was the policy of A. Rosenberg (Minister of the Occupied Territories).

They mocked Russian culture not naively, from their barbarism, but with "scientific justification". The ideology of Nazism clearly indicate that Slavs as "Untermensch" should be part of the destroyed and relocated, and the people should become slaves of the Aryans. Slave culture was not allowed.

Some cultural monuments, such as the pearl of Russian architecture, the New Jerusalem, were blown up by the Germans on purpose. Others, like Tolstoy'a Yasnaya Polyana and dozens of neighboring manor museums, were totally looted. The Germans did not enter Leningrad, but the surroundings — the palaces of Tsarskoye Selo, Gatchina, Peterhof — where the Wehrmacht’s boots had set foot — were turned into ruins.

Chief Keeper of Peterhof MA Tikhomirova - in a letter to her mother: "... it’s so terrible that you can’t find words. The Grand Palace is a ruin without floors, ceilings, roofs, without a church, and a corpse under the coat of arms. From Marley there are smoking ruins, Mon Plesir is turned into a pillbox, disfigured , the parks have been destroyed. You can't even cry because of it, you just turn to stone."

In Pushkin’s estate, Mikhailovskoye was ransacked and his house/museum was destroyed, even Arina Rodionovna’s house, and the old park cut down . An employee of the museum recalled: “The German headquarters settled in the museum. The Germans set up trestle beds, collapsed on old chairs, began to carry valuable things: candlesticks, paintings ... I saw a portrait of Pushkin by the artist Kiprensky in one of the halls. The portrait was lying on the floor. The canvas was pressed through with a boot. In front of my eyes, a German soldier was pouring books into a furnace ... paintings and sculptures were turned into targets for shooting. "

The current state of affairs is historically fair, corresponds to the norms of law and, most importantly, the norms of morality and ethics and does not need to be revised.

Among the thousands of the most famous masterpieces taken out are the Amber Room, the search for which continues to this day.

Such examples do not count.

In total, 427 museums were looted in the occupied territory. Only in the territory of the RSFSR, 1,177,291 items were stolen or destroyed as were 13,000 musical instruments; libraries lost about 180 million books; 17 million cases were removed from the archives or destroyed; more than 3,000 architectural monuments were completely destroyed.

... Therefore, even if one does not operate with the concepts of "morality" and "conscience", it’s easy to look at the question with German practicality and pedantry, if with this far from complete list of the destroyed centuries-old cultural wealth of Russia one compares lists of compensatory restitution, then one has to admit Soviet victorious soldier took pity on Germany. A very modest amount was taken. With this real arithmetic, dear German colleagues, you definitely want to return to the question of restitution? No, if you honestly have something else for us - let's, so be it, let's talk ...

Employees of the Hermitage save the masterpieces that suffered during the shelling.

Employees of the Hermitage save the masterpieces that suffered during the shelling.

Claims history

I will mention that the issue of undisputed ownership of displaced cultural property in relation to Germany has two legal exceptions. They concern:

- property of religious organizations;

- the property of individuals, previously gratuitously seized from them by the Nazis in connection with racial, religious or national identity (I emphasize: forcibly seized, confiscated).

For this part, we do not mind. Our legislation fully complies with this norm of international law. For example, in 2002 Germany transferred 111 stained glass windows from the Church of St. Mary (Marienkirche), previously transferred to Russia and kept in the Hermitage.

But for some reason, some European leaders do not recall this rule of law (in 2005, according to the statement of the then Minister of Culture of the Russian Federation, A.S. Sokolov, representatives of eight countries stated claims to Russia: Austria, Belgium, Hungary, Germany, Greece, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and for some reason suddenly Ukraine).

One articularly interesting example distinguished our Dutch partners. Since the 1990s, they started talking about the return of the so-called "Koenigs collections" - a Dutch banker who collected works of art (Breugel, Rembrandt, etc.). The history of his collection is as follows. In the 1930s, the banker went bankrupt and sold it to a certain businessman, van Beuningen. Later, in turn, he resold (!) to the Third Reich for over 1.4 million guilders - that is, at quite a market price. Until 1945 it was kept in the Dresden Gallery, and then it was exported to the USSR - as property of Germany, subject to legal compensatory restitution. Located in the Pushkin Museum.

And in the 1990s, the Dutch suddenly imagined that it would be good to have this oversold collection now, as part of perestroika and "new thinking," squeeze it out of the Russians for free. Because, they say, it was once "private property".

A few years ago, I had a discussion on this topic with the Dutch Minister of Culture and Education, who strongly demanded that the work of the inter-ministerial commission on the return of the Koenigs collection to the Netherlands be “intensified”.

We explained: no, according to the law, this is not a Dutch collection or even a collection of a Dutch subject. It was sold by them to Germany, and we already got as property of the defeated Reich. So we won’t “activate” the old commission from the 90s, but dismiss it in general.

Due to the lack of subject matter.

A colleague was indignant: how is it that, they say, a Dutch seller, perhaps, Germany "made such an offer that he could not refuse." You had to, you know, poor fellow to sell paintings to the Germans. Perhaps even at a low (!) price. Like, we all (we?) need to do research on this topic ...

It was necessary to remind everyone that for two years Leningrad was in much more difficult conditions than the Dutch millionaire. But from the collections of the Hermitage and other museums of the city no one even gave the Germans a clove from the packaging. The USSR paid a terrible price for it. And what price did Holland pay to “not sell collections at perhaps a low price”?

And therefore I consider the question closed, and the commission is dissolved. In order not to cause unpleasant expectations in dear colleagues.

Five years have passed, the Dutch colleagues never returned to this topic. It seems to me that a firm and reasoned "no" is always somehow clearer in the negotiation process.

Return history

Are there any precedents where displaced values were returned to the former enemy?

In world practice - no.

Why - the Dutch newspaper Volkskrant succinctly explained, just by the way, when the “Koenigs case” arose in the early 90s: “If all the works of art exported during wars over the centuries were returned, there would be hardly any museums in the West”.

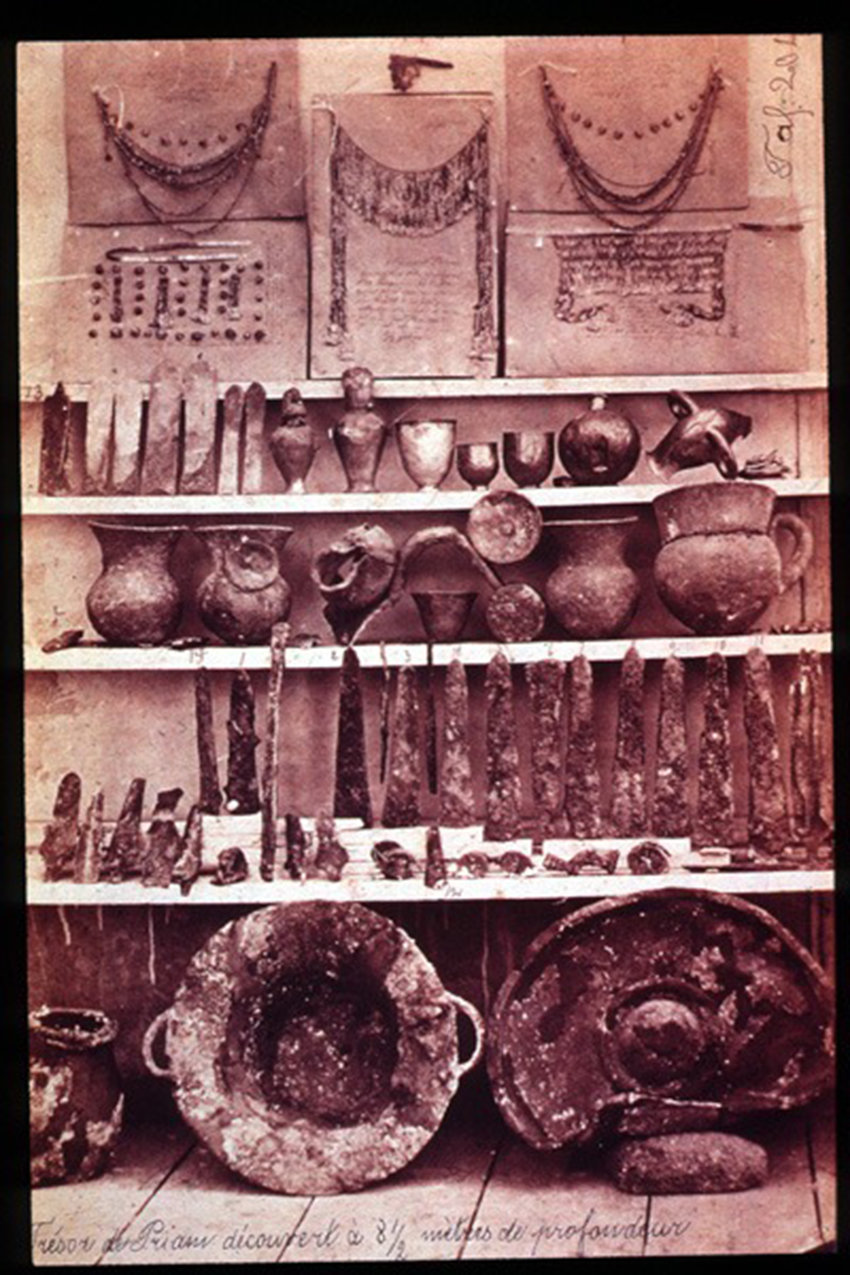

Priam's Treasure in the vaults of the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts. Pushkin since 1945.

Priam's Treasure in the vaults of the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts. Pushkin since 1945.

Take the Louvre, for example. Its collections were formed at the expense of treasures that for centuries were exported from the colonies, the territories of dependent states as military mining. In short - that Bonaparte robbed, and so was rich. From Italy, Spain - paintings and sculptures, from Egypt and Syria - gold tombs, obelisks, etc. The General could not take the Sphinx - due to limited technical capabilities - so at least he shot his nose off from annoyance. From the cannon. Still, Napoleon was a professional gunner.

And how many treasures did the French take out of the Moscow they plundered in 1812? How many died in the fire? After all, only for one burned-out original of the "Lay", we always have to make a complaint to them. But who in France remembers this today? By the way, Alexander I strongly regretted the French when he entered Paris at the head of the Russian army. Compensatory restitution was not perpetrated. This generous soul was a man. This, however, is the property of the real winners.

Or take the famous British Museum. It's still as V.I. Lenin so directly and called it - "a cluster of colossal wealth, looted by England from the colonial countries." Short and succinctly. Today, many are making claims to London - from China and Greece to Tajikistan, Nigeria and Ethiopia. Naturally, the British will never give anything away to anyone. For there are no such precedents in history.

Although ... no. There are precedents. But not in world practice, but ... alas, in ours.

After the Victory in 1945, the USSR and later the Russian Federation repeatedly demonstrated goodwill gestures to the German people.

The return of cultural property to Germany began back in 1949, when the USSR decided to return the archives of Hamburg, Lübeck and Bremen in exchange for the archives of Koenigsberg-Kaliningrad and Tallinn. The process took time until the 1980s, but at first it was an “exchange” process.

And then - it started. The most famous precedent of unilateral disinterestedness was the transfer in 1955 to the Allied GDR collection of the Dresden Gallery (works by Raphael, Correggio, Durer, and others) and the Pergamon Altar ensemble. These treasures were discovered by Soviet troops in 1945, mostly in the quarries near Dresden, mined and in a monstrous state. Damp, covered with water, covered with mould. The fact that they were generally brought back to life is an unparalleled professional feat, first of all by our engineers, and then by Soviet restorers.

By the decision of N.S. Khrushchev, a solemn transfer of all these treasures of the GDR took place - as a sign of friendship and socialist fraternity: a total of 1,240 paintings. Plus another 1,571,995 exhibits from all museums of the USSR. That is, according to some estimates, 4/5 (!) of everything that was take after the war was returned.

It was made from a false sense of class solidarity. For short-term political considerations. Where is it now, this class solidarity? Where is it now, the camp of socialism? They are nowhere ... And we do not have the Dresden collection either.

However, we do not have the right to condemn our forebears today: if the reasons of the 1950s are not close to us, this does not mean that there were no such reasons at all.

Another thing is important: unfortunately, later these manifestations of Russian generosity were interpreted as weakness.

Just as weakness, not as nobility, is how our one-sided “goodwill gestures” were perceived in the 90s. For example, in 1993 Germany received a collection stored at the Pulkovo Observatory (a collection of the Gothic library, the so-called Green Set in Dresden), much of the collection of the Hermitage and the Pushkin Museum. And what about the German side? They did not return anything to Russia.

And in 1998, N 64-ФЗ "On cultural values displaced to the USSR as a result of the Second World War and located on the territory of the Russian Federation" was adopted, in which all of them are declared state property and restrictions are imposed on their uncontrolled transfer.

***

So. There are not and cannot be any "favorable conditions" under which Russia will enter into any negotiations on the subject of "the return of cultural property to Germany." And no need to deceive our German friends: they say, if you behave yourself well, then ... No.

Dear German partners, you won’t give us back 27 million lives? So do not ask us about the impossible.

This question for us is simply non-existent, it is also in no way connected with the constructive business and cultural relations that exist today between our countries. By the way, in terms of culture, these relations are completely sincere, open and friendly.

But the past is closed. It happened. No need to return to it.

Opinion

Irina Antonova, President of the State Museum of Fine Arts. A.S. Pushkin:

- In my opinion, there is no need to raise an issue that has long been resolved at the level of the law. Claims are being made today only in relation to our country. To those who make such claims, I say it is time to recall the incredible damage that was caused to our country, including in relation to our cultural monuments, during the Second World War.

Alexey Levykin, Director of the State Historical Museum:

- Legally, the issue of the return of displaced art collections has long been resolved. All the displaced cultural property that is lawfully located on the territory of Russia - and these include collections that were taken after the war from the territory of the defeated Third Reich - will remain in Russia.

The main problem today is the continuation of the study, publication and presentation of these cultural treasures, which is what our museums actually do. Often these works are carried out together with German specialists. By the way, many joint exhibitions devoted to these cultural collections have already taken place. We can recall those such as the "Age of the Merovingians", "Schliemann's Gold", "Bronze Age". The State Historical Museum took part in the preparation of a number of them.