News:

Five Countries Slow to Address Nazi-Looted Art, U.S. Expert Says

By William B. Cohan

In 1998, confronted by the fact that so much of the art stolen by the Nazis during World War II had yet to be returned to its rightful owners, 44 nations agreed to the Washington Principles, a treaty of sorts that committed its signers to making best efforts to return the looted art. But speaking Monday in Berlin at a conference convened to measure progress in that undertaking on the agreement’s 20th anniversary, the man who negotiated the principles on behalf of the United States delivered a blunt rebuke to what he characterized as foot-dragging by five countries.

“We have made giant strides,” said Stuart E. Eizenstat, a special envoy to the State Department, “toward achieving the goals of identifying, publicizing, restituting and compensating for some of the looted art, cultural objects and books, and in so doing, providing some small measure of belated justice to some victims of the Holocaust or their heirs.”

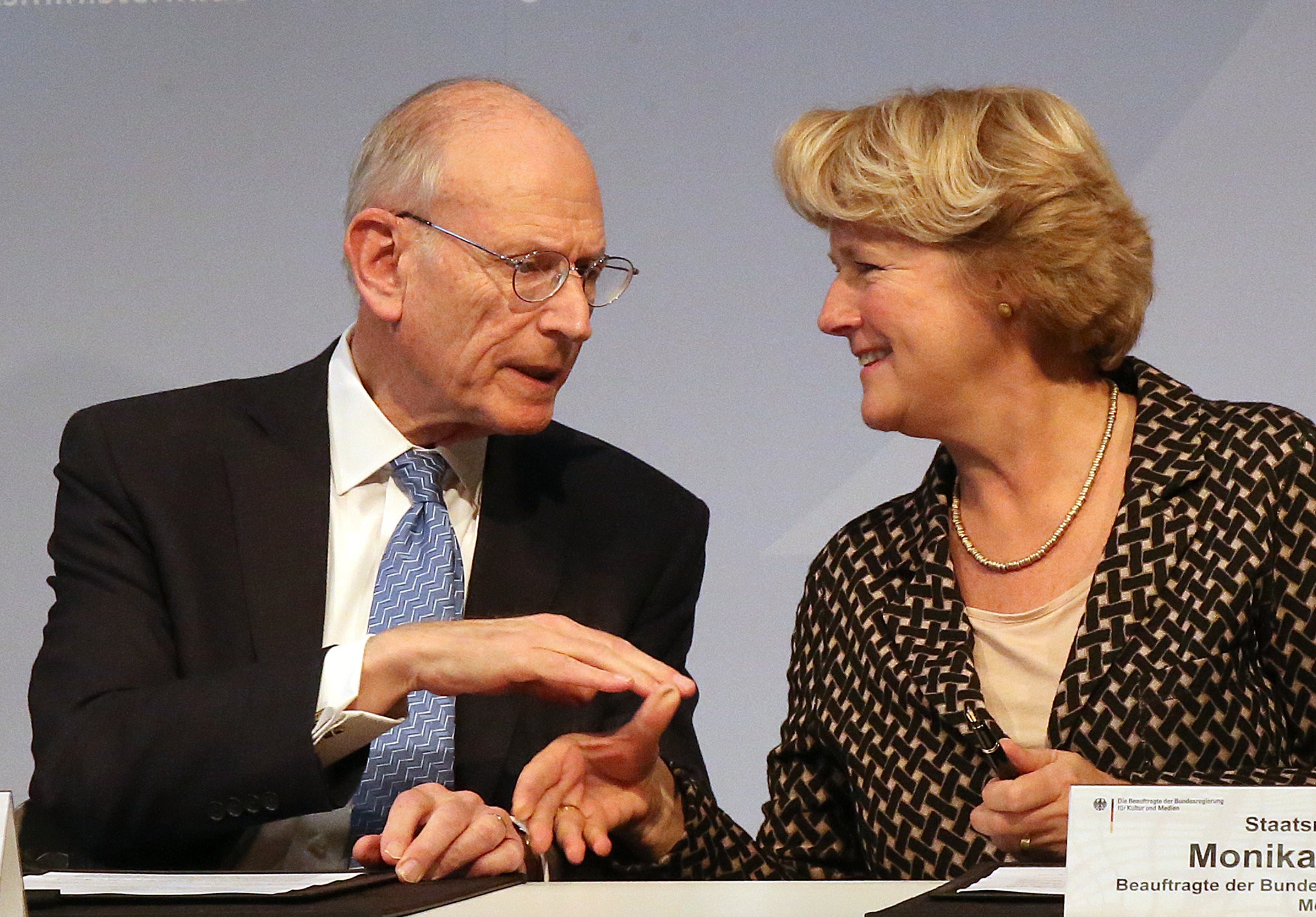

Stuart E. Eizenstat, special envoy to the State Department, and Monika Gruetters, Germany’s culture minister, at the Berlin conference on looted art on Monday. Mr. Eizenstat delivered his remarks there.

Stuart E. Eizenstat, special envoy to the State Department, and Monika Gruetters, Germany’s culture minister, at the Berlin conference on looted art on Monday. Mr. Eizenstat delivered his remarks there.

But, he continued, “We must candidly confront the unfulfilled promises we solemnly made.”

Mr. Eizenstat, now a lawyer in private practice, said an estimated 600,000 paintings had been stolen during the war and that 100,000 remain missing. Here is what he found objectionable about the responses over the decades by the five countries.

Hungary

Mr. Eizenstat was especially critical of Hungary, which he said possesses “major works of art looted on its territory” during World War II “and has not restituted them” despite “being repeatedly” asked to address the matter. At the Vilnius Forum in 2000 (a follow-up to the Washington Principles conference), Mr. Eizenstat criticized Hungary for refusing to carry out the principles, noting that the government in Hungary during World War II had “sanctioned the confiscation of artworks and cultural property” from its Jewish citizens. On Monday in Berlin, Mr. Eizenstat said: “Unfortunately, I cannot report any change of attitude by the current Hungarian government. They have refused to return these artworks to their rightful owners. They have refused to take their historic responsibility for the systematic looting of art from their Jewish citizens.” Some museums in Hungary have researched the provenance of works in their collections but that research has not been made public. And while there is a state order in Hungary about restituting artworks in public museums, Mr. Eizenstat said, “only claimants of non-Jewish origin have received any works back.”

Poland

The Nazis killed about 6.5 million Polish citizens during World War II, including some 3.5 million Jews, but Poland has “largely ignored” the Washington Principles, Mr. Eizenstat said. Some of the looted artworks in Poland were confiscated from Jews who had lived in other places during the war, like the Netherlands, and the art only ended up in Poland as part of later transactions. The Netherlands government has a list of artworks, now in Poland, that once belonged to its Jewish citizens. “It would be useful for joint Dutch-Polish cooperation in provenance research to clarify this situation,” Mr. Eizenstat said, “but to date the Polish government insists they will only handle Polish artworks that had been taken out of Poland.”

Spain

A family has been arguing for years for the return of Camille Pissarro’s “Rue Saint-Honoré, Après-Midi, Effet de Pluie,” which is now held by a Spanish museum

Mr. Eizenstat said Spain has “taken no steps” to fulfill the principles in the past two decades. The framers of the agreement believed that national governments had the greatest responsibility to research the histories of works held in public, government-owned collections. But he said Spain’s approach was evident in its response to an effort by the heirs of the Cassirer family, once noted Parisian art dealers, to get back Pissarro’s 1897 painting “Rue Saint-Honore, Apres-Midi, Effet de Pluie.” The Pissarro, appraised at more than $30 million, is in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid, which was established by the Spanish government after purchasing the collection of a scion of the wealthy Thyssen family and installing it in a Spanish palace. In the years of subsequent legal battles, Mr. Eizenstat said, “the Spanish government took the position that the Thyssen Museum which possessed” the stolen Pissarro “was a private museum not covered by the Washington Principles.”

Russia

President Vladimir Putin of Russia and Chancellor Angela Merkel of Germany touring an exhibition at the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg in 2013. Ms. Merkel was scheduled to speak that day about Russian restitution of artworks taken from Germany in the war, but her remarks were canceled as tensions over the issue mounted.

President Vladimir Putin of Russia and Chancellor Angela Merkel of Germany touring an exhibition at the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg in 2013. Ms. Merkel was scheduled to speak that day about Russian restitution of artworks taken from Germany in the war, but her remarks were canceled as tensions over the issue mounted.

The Red Army Trophy Brigades took many artworks from the Germans after the war, including some that had been stolen from Jews by the Nazis. At first, Mr. Eizenstat said, the Russians seemed sympathetic to the restitution cause, and even announced the return of a work at the news conference that followed the issuance of the principles, in 1998. Since then, he said, there has been some provenance research at Russian museums that is recorded on public electronic databases. “But there has been no restitution of any Nazi-looted art,” he said, “nor any process for their identification or handling of claims.”

Italy

Mr. Eizenstat said Italy, too, started off well enough — publishing a catalog of art treasures lost during the war, including those that once belonged to Holocaust victims. And Mr. Eizenstat noted that, in 2001, the Italian government created the Anselmi Commission, which made recommendations about how Italy could comply with the principles. “But their recommendations have been largely ignored,” he said. “Unfortunately there has been no provenance research or listing of possible Nazi-looted art in their public museums by the Italian government.” He said Italy seems only to care about “what the Italian government lost” and said Italy’s cities and regions, where much of the country’s art collection is maintained, “have ignored” the Washington Principles.

Representatives from the five countries did not respond Monday to requests for comment or could not be reached. Each of the cited countries has defended its actions in the past. Hungary, for example, has said that it had the right to nationalize property that was left behind by Jewish families that fled the country.

Mr. Eizenstat did strike some optimistic notes and found, overall, that the glass “is slightly more than half full.” He noted that Austria has restituted more than 30,000 artworks and that 42 Dutch museums had recently discovered more than 170 artworks with problematic provenances. He said in an interview that the Germans are set to announce at the conclusion of the conference that Germany has restituted more than 16,000 artworks, including 5,746 “art objects” to Holocaust survivors during the past 20 years.

Mr. Eizenstat is writing a more substantial report, due next October, at the request of the State Department, in order to comply with a recently passed federal law, the Justice for Uncompensated Survivors Today Act. It will give a more detailed assessment of how well, or poorly, countries, including the United States, have complied with the Washington Principles.