Israeli museum officials insist they are committed to identifying and restituting looted artworks in their collections. “We have been and continue to be proactive in this field,” says Snyder, who in January assumed the newly created role of international president for the Israel Museum’s worldwide activities, after 20 years as director. (His successor, Eran Neuman, took office on February 19.)

But the gap between the Peleg and Snyder positions is filled with thorny questions. How and why did art looted during World War II end up in Israel? How many significant pieces of looted art are there in Israeli collections? Why has it taken so long to identify these works and track down their rightful owners?

Israeli museums aren’t the only unlikely repositories of disputed works. Last September, the Neue Galerie in New York, whose co-founder, Ronald S. Lauder, has led international efforts to restore art stolen by the Nazis to their rightful owners, agreed to restitute Nude, a 1914 painting by Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, to the heirs of the family from which it was looted. And the Metropolitan Museum of Art is embroiled in a lawsuit brought by the estate of a Jewish businessman who fled the Nazis over rights to The Actor (1904–05), one of the most famous Picassos in the museum’s collection.

Most Nazi-looted cultural objects in Israel arrived via the Jewish Restitution Successor Organization. Founded in 1947 in New York by various American and international Jewish organizations, the JRSO viewed itself as the official heir of unclaimed Jewish assets after the war and Holocaust. The art, books, and Judaica that once belonged to Jewish families were amassed at various collection points in Germany. About 40 percent of these looted assets was turned over to the JRSO, another 40 percent was sent to the United States, and the remainder was divided between Jewish communities in Australia, South Africa, and elsewhere. The recipients often sold these assets and used the revenue to aid Jewish refugees.

The key figure in bringing this JRSO trove to Israel in the 1950s was Mordechai Narkiss, director of the Bezalel National Museum, the precursor of the Israel Museum. In those early postwar years, no thought was given to provenance because there was a widespread conviction that Israel, as the new Jewish homeland, should be a main recipient of looted cultural objects that went unclaimed. “When Narkiss brought objects from Europe to Israel, he believed he was saving them,” says Elinor Kroitoru, Hashava’s head of research. “Nobody back then thought that someday people would come here to claim them.”

It is only in recent years that Israel has redoubled efforts to identify and restitute stolen art and other cultural objects. The collapse of Communist regimes reopened the issue in the 1990s with the discovery of stolen artworks in Russian and Eastern European museum collections. But the resurgence of interest in looted art came a half-century after the war, making the task of restitution all the more difficult. Children of collectors who were killed in the extermination camps are fast disappearing themselves, leaving few potential heirs with any direct knowledge of the stolen art. And documents to trace the provenance of these works have become harder to locate, if they exist at all.

In the meantime, many looted paintings and drawings flowed into the marketplace. They were then purchased, often innocently, by collectors and eventually were donated as bequests to museums. Among the more startling examples is Boulevard Montmartre, matinée de printemps, painted in 1897 by Camille Pissarro as part of a series portraying the famed Paris thoroughfare in different weather and seasons. This Impressionist masterpiece was owned by Max Silberberg, a prominent Jewish industrialist from Breslau, Germany, who sold most of his art collection at auction and was later murdered in Auschwitz. It was purchased in 1960 by a wealthy American couple, John and Frances Loeb, who bequeathed the painting to the Israel Museum in 1997. “We have many Pissarros in the museum,” says Snyder. “But of all of them, this was probably the most important one.”

Put on display, the work came to the attention of Gerta Silberberg, daughter-in-law of Max Silberberg. She negotiated an agreement in 2000 that allowed the painting to be displayed at the Israel Museum while she was alive. After Gerta Silberberg died, her heirs sold the Pissarro at a Sotheby’s auction for $32 million in 2014. But her estate donated some of the funds to the Israel Museum to acquire works in memory of the Silberbergs.

One of the issues raised by the Silberberg case is whether the Pissarro and the rest of the collection was sold under duress. Records show that the works were auctioned in Nazi Germany in 1935, before the period of forced sales began. The Pissarro actually sold for a record price at the time. If the Silberbergs had survived the Holocaust and retained the assets from the auction, says Snyder, “it might have been harder to make the case for restitution.”

Because of its deep pockets, the Israel Museum has the resources to trace the provenance of works in its vast collection that might have been plundered by the Nazis. Two full-time researchers are assigned to that task. The museum also maintains a website (http://www.imj.org.il/imagine/irso/en) that lists all paintings, drawings, prints and items of Judaica in its collection believed to have been looted. Over the last decade, about 20 restitutions have been made.

But smaller institutions don’t have the resources available to the Israel Museum, and sometimes they are embarrassed when the provenance of works in their collections is revealed. That was the case with The Beggar, painted in the 1920s in Paris by the Minsk-born Jewish artist Eugeniusz Zak and stolen from an unidentified art collector by the Nazis. Brought over to Israel by Narkiss as part of the JRSO cache, the painting ended up in the collection of the Museum of Art in Ein Harod, Israel. While on display there, it was identified in 2015 by a Polish Ph.D. student as looted art.

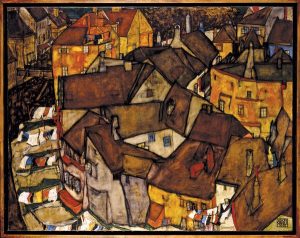

Zak is obviously not in the same category of Pissarro or Schiele. In fact, few looted artworks worth millions of dollars are believed to be in Israel awaiting restitution. Of the 2,000 cultural objects that the Israel Museum received from the JRSO, many were domestic items that would have had more personal and emotional importance than artistic or material value.

In the early 20th century, middle- and upper-middle-class Jews affirmed their social standing by purchasing paintings and drawings. “They may not have bought Rembrandts, but they could afford local, contemporary painters,” says Snyder. The museum made a decision two decades ago, he adds, “that if people came forward to claim things—even if they were objects of no consequence—we had to help them.”

Judaica is a separate issue. Many Jewish ceremonial objects of artistic value—including Torah holders, Shabbat candlesticks, hand-washing pitchers, and menorahs, all in silver—survived the Holocaust for the most perverse of reasons. The Nazis collected the finest Judaica, intending to build a museum that would serve as a repository for the relics of the people and culture they sought to annihilate.

Understandably, most of the Judaica looted from synagogues destroyed during the war and transferred to Israel will remain in its museums.