News:

Ronald Lauder, Advocate of Art Restitution, Says His Museum Holds a Clouded Work

By Serge F. Kovaleski

When it comes to art plundered in Europe during World War II, Ronald S. Lauder, chairman of the Commission for Art Recovery, has been very much the face, and soul, of the restitution movement.

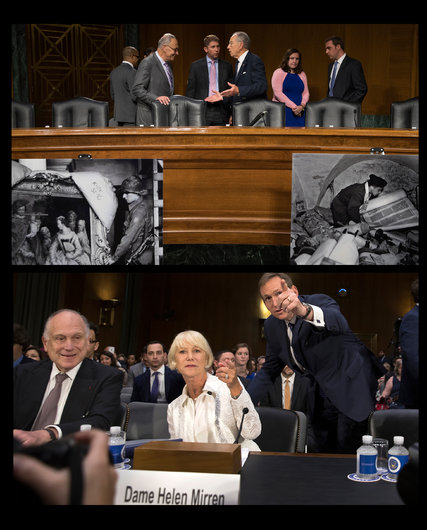

In June, he was center stage at a Senate hearing on a bill to ease the way for the return of art looted by the Nazis, testifying alongside the actress Helen Mirren, who last year starred in “Woman in Gold,” a film about a Jewish heir’s struggle to retrieve her family’s stolen possessions.

The cosmetics magnate and philanthropist Ronald S. Lauder, left, and the actress Helen Mirren testified in June at a Senate Judiciary subcommittee hearing on a bill to ease the way for the restitution of art looted during the Holocaust.

Away from the spotlight, though, Mr. Lauder has been criticized for more than a decade by other restitution advocates and scholars. They say his own practices in detailing the provenance of works within a Manhattan museum he co-founded, the nonprofit Neue Galerie, and his private collection have not been as transparent as they should be.

Now there are signs Mr. Lauder has heard the criticism. To elevate their research, he and his staff have hired additional experts, are overhauling the museum’s website to ensure that provenances are more detailed and soon plan to announce a surprising byproduct of their labors: One of the Neue Galerie’s major works has a clouded history and may be returned to people who say they are the rightful owners.

Mr. Lauder, 72, would not identify the piece or its creator during an interview, saying that negotiations on its return were being finalized. He did say he was surprised that a work with a disputed provenance had made it into the museum, which focuses on art created in Austria and Germany from 1890 to 1940.

The Neue Galerie in Manhattan

The Neue Galerie in Manhattan

The Neue Galerie’s collection includes major works by Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele and was assembled largely from art donated by Mr. Lauder, an heir to the cosmetics fortune created by his mother, Estée Lauder, and by his friend Serge Sabarsky, an art dealer and expert on German and Austrian Expressionist art who died in 1996.

“If you asked me a year ago, ‘Do we have everything there?’ I would have said yes, because that is what I was told,” he said of the museum’s provenance research at the time. “I was told there were no questions about the pieces we had.”

Others would not be so surprised.

Soon after opening the museum in 2001 in a Fifth Avenue mansion that was once home to the society doyenne Grace Vanderbilt, wife of Cornelius Vanderbilt III, Mr. Lauder faced criticism that the provenances listed for many works were incomplete. He asked for patience.

“We are only 12 to 14 months old, and it is taking us more time to get going and do the research necessary,” he said then.

A review last week showed only minor progress. The museum, for example, still posts few dates for when its holdings changed hands — crucial information, according to experts. Given the extent of Nazi looting and the art sales made by Jews under duress in the years leading up to and through World War II, any work that was transferred from one party to another in Europe during that period typically receives the highest level of scrutiny.

“You would think that his gallery would be the most transparent, but it provides the minimal amount of information, which I do find surprising,” said Elizabeth Karlsgodt, an associate professor of history at the University of Denver and an expert on Nazi art looting.

Ms. Karlsgodt added, “If his collection is entirely clean, the museum website should prove it with more detailed provenance information.”

Marc Masurovsky, who jointly founded the Holocaust Art Restitution Project in 1997, said his group has long wanted to assess Mr. Lauder’s private collection but was told that Mr. Lauder was unwilling to participate.

“We hit a stone wall,” Mr. Masurovsky recalled. “The question for us is whether he did due diligence to make sure his collection is as clean as driven snow.”

Mr. Lauder has long said that he viewed his staff’s research as thorough and that few claims to his art have arisen despite the many times it has been displayed in public. But he asked Agnes Peresztegi, a Paris-based lawyer and expert on Holocaust era property claims, in recent months to seek more information on the museum’s holdings, including more detailed provenances.

“I am not happy because I think we should have had more information,” Mr. Lauder said in the interview, “and we are doing it.”

Ms. Peresztegi, who is president of the Commission for Art Recovery, said of the Neue Galerie, “I can’t deny that there are museums whose websites are more forthcoming than the museum’s.”

Ms. Peresztegi said that a decision was made at the museum six or seven years ago not to display transfer dates until a full provenance for a work became available.

Under its new policies, the museum will post provenance information piecemeal as soon as it has it, officials said. It is repairing a link between the gallery’s database and its website that has been broken for about two years — a break, officials said, that had prevented a more timely updating of information.

Mr. Lauder has been on a mission to restitute art since the late 1980s. He has been chairman of the Commission for Art Recovery since it was formed in 1997 to negotiate with governments, museums and other entities as part of the effort to retrieve art wrongfully taken from Jews by the Third Reich and its allies.

Over the years, Mr. Lauder says, he has returned three works from his personal collection because of concerns over their rightful ownership. But now, for the first time, he is faced with the prospect of returning an artwork held by the museum.

All Ms. Peresztegi would say about the work in question was: “The Neue Galerie is in the process of evaluating the provenance information of an artwork, and discussion about restitution is currently ongoing.”

In the past, Mr. Lauder faced criticism that he did not do enough as a board member of the Museum of Modern Art to chastise the institution for fighting to hold onto works by Schiele and by George Grosz that were claimed as looted art.

In both cases, Mr. Lauder recused himself and said he refrained from taking a vocal position because he was chairman of MoMA when the claims arose. But he said that he worked behind the scenes to push the museum to consider the claims fairly.

Regarding the Grosz art, which involved a claim to three works, he said he also asked a lawyer for the Commission for Art Recovery to review the case. The commission ended up filing a legal brief in support of the plaintiffs, who were suing to recover the art.

Jennifer Kreder, a lawyer who helped write the brief, said: “Ronald Lauder has possibly accomplished more behind the scenes for the restitution of Nazi-era art than any other single person.”

(In the Grosz case, MoMA ultimately prevailed with a legal victory. As for the Schiele painting, “Portrait of Wally,” the Vienna museum that had lent it to MoMA retained the work as part of a settlement under which it paid $19 million to the heirs of the woman from whom it had been stolen by a Nazi.)

Ray Dowd, a lawyer for heirs of Fritz Grünbaum, a Viennese art collector and cabaret performer who was killed by the Nazis, said Mr. Lauder’s representatives had stonewalled when he sought the return of a Schiele drawing, “I Love Antitheses.”

“The evidence is particularly strong,” he said, “that the drawing was stolen from Mr. Grünbaum, but they jerked us around and said they would not give us any information on how it was acquired.”

Mr. Lauder confirmed through a spokesman that he owns “I Love Antitheses” and would only say, “The cornerstone of the Grünbaum matter is an internal family inheritance dispute.”

These days, Mr. Lauder said he has all but stopped buying German and Austrian Expressionist art. There are often provenance questions associated with the period, he said, and he has plenty of such works. And, he added, sellers who identify him as a prospective buyer with a passion for that period often try to charge higher prices.

Years ago, when he was buying Expressionist works, Mr. Lauder said, the provenance information available was much less reliable than what exists today on the internet. Still, Mr. Lauder said he was determined to make the Neue Galerie’s provenance research a gold standard for the art world.

During the interview, he said he recognized that, given his profile as a restitution advocate, he will continue to be subject to greater scrutiny.

“When you walk around with a white suit on, anything shows on it,” he said. “I understand that.”