News:

Mission impossible: German libraries try to return Nazi-looted books

By Polina Garaev

Dealing with their shameful past after years of apathy, libraries across Germany search for the rightful heirs

A well-known secret is kept in a book-filled room at the Hamburg University Library. The publications which fill the shelves don't necessary have a common theme, and only few of the students who visit it know that they are surrounded by evidence of a shameful past: All of the books stored in that room are looted property, taken from Jews by the Nazi authorities.

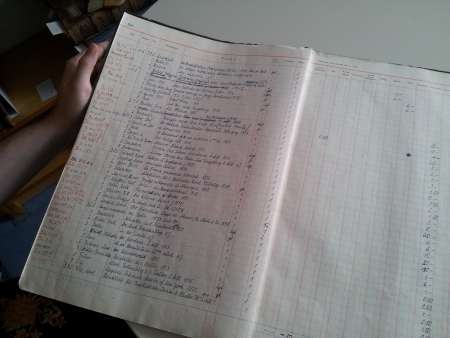

In fact, in most of the major libraries across Germany, one can find books which were taken by the Nazis, but port cities such as Hamburg, have particularly extensive collections. “All books that came to the library between 1933 and 1945 are somewhat under suspicion,” admitted Dr. Anna von Villiez of the university's library, “especially those which were donated to us by the Gestapo, according to the old ledgers, which luckily survived the war.”

Polina Garaev"Ledger"

In Berlin, an accidental look into the records of the Central State Library (ZLB) led to an unpleasant discovery. In 1943 the library knowingly bought 40,000 looted books from the city of Berlin, for the price of 45,000 Reich Marks. “My boss started to research the subject on his own initiative, and discovered this letter exchange with the city administration, in which the library clearly requested the books be taken from the Jews,” explained Sebastian Finsterwalder, who's now tracing their origin.

“The city's answer was, 'you can have the books but you would need to pay, because they belonged to enemies of the Reich and the money will be used for the solution of the Jewish question,'” he continued. “So the library even knew what the money would be used for.”

Polina Garaev"Sebastian Finsterwalder"

Now, after decades of ignoring the tainted collections, libraries are attempting to return the books to their owners, or more likely – to their heirs. In 2005, library researchers in Hamburg began to locate the “Gestapo-donated” books still in its possession, and to search them for notes, dedications, and bookplates to indicate their owners. “Once we have a name, we turn to databases, like the Yad Vashem archive or ancestry.org, to find out more,” explained von Villiez.

Finsterwalder's team, however, can't narrow down the list and is forced to look into every single book. Since 2009, when they began, only a quarter of the library's inventory was scanned. They too tried to keep the suspicious books in a separate room but couldn't handle the amount.

“About 2,000 of the acquired books were entered to a special ledger and given an inventory number beginning with the letter J, and we found about 1,500-1,600 of them,” told Finsterwalder. “But the rest, which were entered after the war, were marked as 'gifts' and got mixed with the actual donations. So now we have no way of knowing which 'gift books' were looted, unless we find a name or other traces insode the books.”

These restitution efforts are fairly a new development. “In the first decades after the war the political atmosphere in Germany was not in favor of the restitution process,” confirmed von Villiez. “Both in the German administration and in public institutions like libraries, there was a continuity of personnel after the war, and it created a reluctance to deal with restitution claims.”

Without a legal requirement to do so, even the 1998 Washington Conference – which instituted a moral obligation for all public institutions of the signing nations to search for Nazi looted property – had little impact. “It usually takes a generation until the look back into the past becomes bearable,” noted von Villiez. “But the research done in this field since the 90's made clear to which extent Nazi-looted books were integrated into the stacks of German libraries. The political atmosphere changed from denial to a growing openness towards the past and the reflection on librarians’ role in it.”

University of Hamburg"Exhibition at the University of Hamburg"

University of Hamburg"Exhibition at the University of Hamburg"But the passing time also poses a challenge. “As the survivors are mostly not alive any more, we are looking for their children or grandchildren, who can be harder to locate,” said von Villez. “But at the same time, new sources are made available with the ongoing digitalization of archives, which helps in the global search for heirs.”

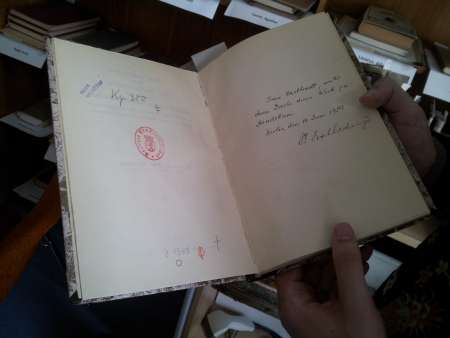

“With art it's easier because the documentation is better,” explained Finsterwalder. “You only have this one piece, and it's documented somewhere who painted it and who bought it. But with books there's no record, and there are many copies with no way of distinguishing between them, unless that person wrote his name inside or left other traces, like marking passages or writing notes which can be matched to other booked already identified.”

So far, the library in Hamburg made 21 restitutions, around 500 books in total, with some heirs deciding to donate the books to the library or to another institution.

Finsterwalder facilitated the return of a similar number of books, but admits: “To look through all the books is work for many lifetimes. We still don't know how many looted books we have, and most of them we will never be able to return.”

But there are success stories: In 2008, a Der Spiegel report on a looted books exhibition at the Berlin library led to a rare return of a book to its original owner. A Florida resident recognized the name 'Wolfgang Lachman' on the inner cover of a book featured in the German article, and called his friend in New York, Walter Lachman, to see if there's a connection. “It's me,” replied the man. Lachman, who changed his first name after escaping the Nazis and arriving to America, never told his story to his family. “Getting the book back unlocked something in him,” said Finsterwalder. “He began going to schools and sharing his story for the first time.”

Polina Garaev"Book in Hamburg University Library"

Polina Garaev"Book in Hamburg University Library"The returned books usually have no real value, but that's seen as irrelevant. “They carry memories and connect people to their past, especially the second and third generation, who sometimes know nothing of what happened to their family,” Finsterwalder added.

Some don't want to know, he admitted, “but at least we give them the choice. The worst reaction I ever got was no reaction.”

“Giving back these books is a matter of principles,” stressed von Villez, while insisting this does not erase the guilt: “It's only a gesture to recognize the past and to return what does not rightfully belong to the library. The fact that the library profited heavily from the persecution of Jewish citizens cannot be undone.”

Yet the importance of this research is not necessarily reflected in the number of its practitioners, or the resources they are granted. “99% of them are volunteers, temp workers, or library workers doing this part time, and that affects the work they can do,” lamented Finsterwalder. “There will never be enough recognition or outrage over this topic, which would force Germany to offer enough funding. I think most institutions came to this conclusion. I know that my work will never be over, but on my part, I will continue doing what I can.”

Polina Garaev is the i24news correspondent in Germany.