News:

People of the (stolen) book: Did Israel's National Library engage in systematic theft?

By Ofer Aderet

New book casts a shadow on the way the National Library acquired some of its most treasured items, such as Torah scrolls from Yemen and books belonging to Palestinians and Holocaust survivors.

The National Library in Jerusalem. Photo by Emil Salman

Shalom Ozeri’s family came to Israel in 1949 from the Yemeni port city of Aden and was sent to the immigrants’ camp at Rosh Ha’ayin. A few months later, packages containing the family’s Torah scrolls and holy books began arriving. Valuable items included a tikhlal — a Yemenite Jewish prayer book dating back 500 years — and a manuscript of the Mishna in two parts.

When Ozeri went to pick up the parcels from customs, he discovered that someone at the immigrants’ camp had opened a package and stolen the tikhlal, one part of the Mishna manuscript and other items.

“Of course I tried every way I could to find the stolen items,” Ozeri related years later. “But unfortunately I didn’t solve this mystery.”

In the 1990s Ozeri learned, completely by chance, that the lost part of the Mishna was at the National Library in Jerusalem. In 1994 the library agreed to give it back.

Back then the library’s deputy head was Prof. Robert (Reuven) Bonfil of Hebrew University’s Jewish history department. Today he remembers “cases where for some reason there was scope for considering the removal of items from the library’s collection and returning them to people who claimed ownership,” he told Haaretz.

This case is discussed in a new Hebrew-language book “Ex-Libris: Chronicles of Theft, Preservation, and Appropriating at the Jewish National Library” by Dr. Gish Amit, an expert on the cultural aspects of Zionism.

The theft of Ozeri’s tomes was part of a “collecting operation” of books belonging to Yemenite Jews who came to Israel in the late ‘40s and early ‘50s. Thousands of books found their way to academic institutions, libraries, synagogues, museums and private collections.

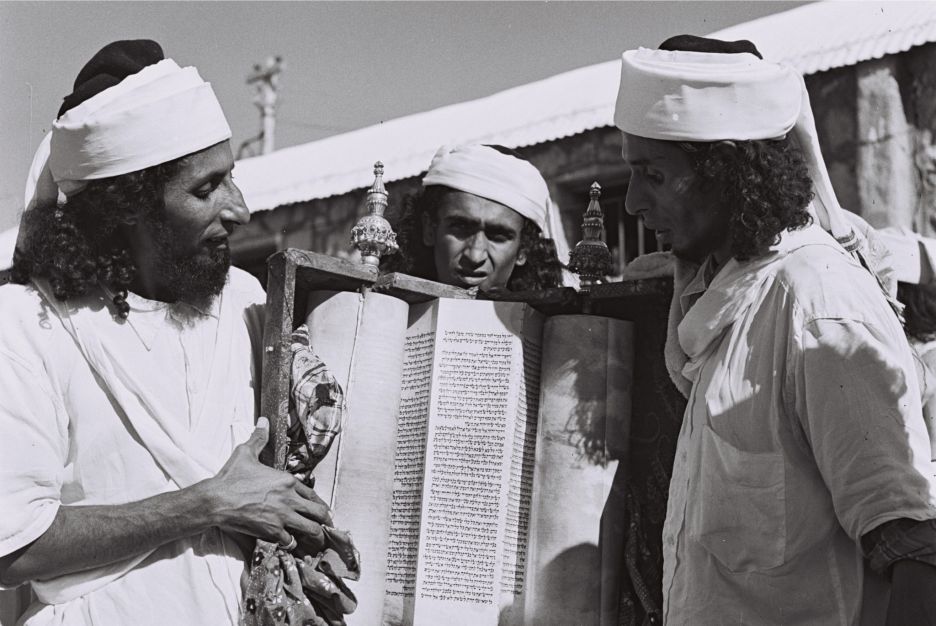

Immigrants from Yemen after arriving in Israel (Fritz Cohen, Laam)

Immigrants from Yemen after arriving in Israel (Fritz Cohen, Laam)In the library’s archive, Amit found a list showing that the library held 430 such books. The institution has documented only one more case, in 1951, when it returned stolen books to a Yemeni immigrant. In archives around the country the acts of thievery were documented.

Rabbi Yehiel Umassi, a Yemenite spiritual leader who immigrated in 1950, told about one such incident. Before boarding the plane he entrusted 10 of the community’s Torah scrolls to a man from the Jewish Agency. When he showed up to pick them up from the JA’s storehouses in Tel Aviv they weren’t there. In a letter that year to the agency, he wrote: “Upon their arrival ... the parcels were unwrapped, the crates were broken, the sacks were torn and the books with valuable things were stolen.”

Another prominent Yemenite rabbi, Yehyia Alsheikh, had a similar story: “We went to the Jaffa port to ask for the books. They told us: ‘Bring proof that these books are from your synagogue.’ So I said, ‘What proof do you want? Our names are on the books.’”

Dr. Gish Amit (David Bachar)

Dr. Gish Amit (David Bachar)According to Amit, “The fact that the library didn’t bring to the public’s attention the affair of the collecting or theft ... and the fact that these manuscripts remained in the library’s storage rooms without any active effort by the library to return the books to their owners — these are the most disturbing and problematic sides of the affair.”

The National Library says it believes that the 430 Yemenite manuscripts were transferred to it by the Jewish Agency. They can be read both at the library and online.

“The library has little information and very few details on the manuscripts’ original owners, so it cannot act beyond what it has already done: to devotedly and responsibly preserve a cultural treasure of Yemenite Jewry,” the library told Haaretz in a statement.

“In cases where private ownership of a manuscript in the library’s collection is indisputably proved, the library will return the manuscript to its owners. This is what the library has done in the past and what it will do in the future.”

Jewish forces advance in Jerusalem

Amit, 42, became interested in the issue after he encountered the story of another collection that had found its way to the National Library. In 2007 he was seeking a research topic in the Jewish literature department at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. He noticed a document on the economic aspects of a National Library project in 1948. “I gradually found documents on the affair until I realized I had discovered an important event,” he recalls.

The 1948 project took place in Jerusalem during the War of Independence. People from the National Library and Israeli soldiers collected tens of thousands of books, periodicals and manuscripts left behind by Arabs who had fled Jerusalem.

The National Library in Jerusalem (Emil Salman)

The National Library in Jerusalem (Emil Salman)

A library document from March 1949 discusses the mood after Katamon and adjacent Jerusalem neighborhoods had been taken. Bibliophiles, concerned about the fate of books in those neighborhoods, requested that the university collect and safeguard the volumes.

According to the library officials in the document: “We did not conceal from the authorities our hope that a way would be found to transfer some of the books, perhaps most of them, to the university’s possession.”

Amit notes the complexity of the story. “On the one hand, the books were collected and not burned or left in the abandoned houses in the Arab neighborhoods that had been emptied of their inhabitants. Had they not been collected their fate would have been sealed — not a trace of them would remain,” he writes.

“The National Library ... protected the books from the war, the looting and the destruction, and from illegal trade in manuscripts. It also protected the books from the long arm of the army and government institutions.”

A second document from that year found by Amit in the library revealed a more fraught aspect.

“When the decision was made to see to these books, we set out with reservations about ‘what people would say,’” the document read. “Indeed, slanders were heard that ‘the National Library people are pouncing on the plunder,’ but we realized that if we did not commit to rescue these books, they would be destined for theft and destruction. So all the initial reservations disappeared.”

Haaretz too reported on the affair at the time. “Abandoned libraries under the custodianship of the National Library,” read a headline in April 1949.

“Since the end of May last year the National and University Library has rescued from loss and destruction about 30,000 books, as well as hundreds of manuscripts and periodicals in Jerusalem. This is the property of institutions in the areas of fighting — therefore they could not continue functioning — or of individuals who fled places taken by Jewish forces,” Haaretz reported.

“One of the people from whose homes books were taken was Khalil Sakakini, a prominent Christian-Arab teacher, writer and intellectual. On April 30, 1948, he fled his home in the Katamon neighborhood. Eventually, he described his separation from his books in his diary: ‘Farewell, my chosen, inestimably dear books. I do not know what your fate has been after we left. Were you plundered? Were you burned? Were your transferred, with precious respect, to a public or private library?”

The Sakakini family in their Jerusalem Home. Khalil is second on the left

The Sakakini family in their Jerusalem Home. Khalil is second on the left

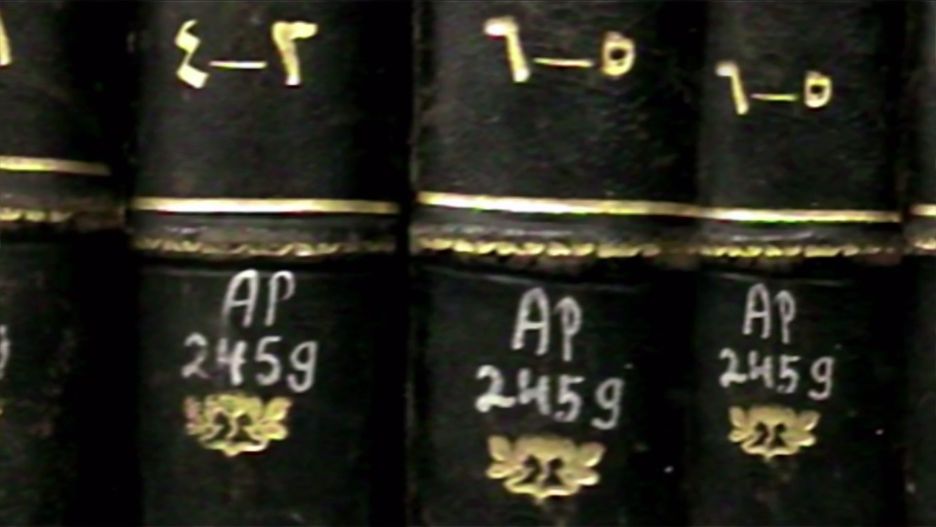

Sakakini died in 1953. Amit found his name in a National Library report from March 1949 listing 60 book owners who came to the library. In 1950 the books were catalogued by their owners’ surnames. Since the 1960s they have been marked “A.P.” — “abandoned property.”

Not very righteous

Prof. Zeev Gries, an expert on the history of Jewish books at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, proposes a broader perspective.

“There wasn’t any intentional policy here of stealing books. They collected, preserved and in fact rescued the books that were found abandoned. And there was no Palestinian institution to work with. It’s a sad story,” he says.

“I’m not sure, to put it mildly, that anyone in the Arab countries worried about books or property left behind by a million Jews who left these countries or were expelled from them — similar to Israel, which isn’t always very righteous in all its deeds.”

Books that belonged to Palestinians, marked as abandoned, in the National Library. (Still from the film The Great Book Robbery)

Books that belonged to Palestinians, marked as abandoned, in the National Library. (Still from the film The Great Book Robbery)

As the National Library said in its statement to Haaretz, “The library has a collection of about 6,477 titles (mostly books and manuscripts), most of them taken from private libraries in homes left in 1948. The entire collection is catalogued and identified as an A.P. collection.

“The collection is the responsibility of the custodian of absentee property at the Finance Ministry, and any decision about it is in the custodian’s hands. The custodian requested the library to store the collection and enable access.”

At the library’s archive, Amit came across other incidents of gathering books between 1945 and 1955. Amit tried to link them and learn how the Zionist movement “denied the cultural heritage of other groups in Israel by taking possession of their intellectual treasures,” as he puts it.

Along with the books belonging to Yemenite Jews and Jerusalem Arabs, Amit learned of the treasures of the Diaspora. Hundreds of thousands of books belonging to Holocaust victims were stolen by the Nazis and collected by various organizations after the war.

The National Library took part in these efforts. In 1945 Hebrew University founded a “Diaspora treasures committee” that sent representatives to Europe to win back as many books as possible. Amit refuses to view this as a heroic rescue operation; he sees it as a political story, too.

“Being Zionists, the members of the ‘Diaspora treasures’ committee believed that the future center of Judaism was in Palestine/Israel,” Amit writes in his book.

“They doubted the power of the Jewish communities to rise from the ashes .... They cast considerable doubt on the right of the remnants of Jewish communities to take possession of cultural assets. From a historical perspective, the transfer of books to Jerusalem, especially the preference given to the National Library, is not to be taken for granted.”

He cites a 1945 letter by Avraham Ya’ari, one of the National Library people sent to Europe to rescue books, to Cecil Roth, chairman of the Jewish Historical Society in London. In the letter, Ya’ari explained why the books should be sent to the Holy Land, citing Roth’s contention that it was time to build, not destroy.

He said it wasn’t constructive to leave valuable books and manuscripts in the hands of small communities where no one would open them. That would be the abandonment of books to book dealers, or to mice and worms. It was better to rescue them for the Jewish people and house them in Jerusalem, where they would be read.

Amit says this reflects the “refusal by Zionism and Israel to acknowledge that Jewish culture can also exist outside the territorial boundaries of the Land of Israel.”

The documents taught Amit a fascinating lesson about the treasures in archives everywhere. “An archive is always just as connected to the present and the future as it is to the past,” he says. “The documents preserved in an archive attest to historical injustices still waiting to be rectified.”

The National Library added that the books in question “came to it from institutions and individuals who saw the rescue of these collections as a mission .... Hundreds of thousands of researchers from Israel and abroad have been exposed to these collections. It is doubtful this research activity would have been possible without this professional preservation, documentation, cataloguing and accessibility.”

http://www.haaretz.com/jewish-world/jewish-world-features/.premium-1.635073