News:

Anne Sinclair revisits Nazi looting of Paul Rosenberg’s art gallery

By Anne Sinclair

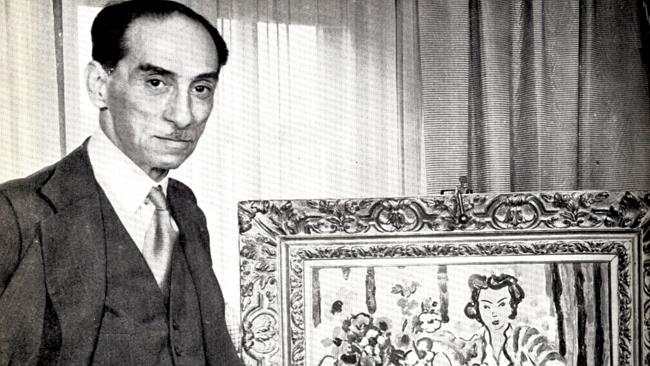

Paul Rosenberg with a Matisse painting in the 1930s.

On June 10, 2013, 74 years after my grandfather was forced to abandon his gallery located at 21 rue La Boetie in Paris, I had the honour to unveil a white marble plaque on the facade of the building.

The plaque bore his name and those of famous painters he used to show, many of whom were his closest friends - Picasso, Braque, Matisse, Leger among them. I was pleased that the plaque explained who my grandfather was and how the building, which had been devoted for 20 years to art, had been looted and transformed into a Nazi propaganda office during the German occupation of France. From now on, everyone passing by will read the plaque, learn who the art dealer Paul Rosenberg was, and discover how a criminal regime transformed my grandfather’s gallery from a temple of beauty to a storeroom of depravity.

Twenty-one rue La Boetie, the gallery owned by my grandfather was piled to the rafters with “accursed” works, the kind that the Nazis called entarteteKunst , “degenerate art”. The term referred to any art that, for the German regime, departed from the canon of what the Nazis considered traditional.

“German people, come and judge for yourselves,” said Adolf Ziegler, the president of the Reich Chamber of Visual Arts, as he infamously opened the Munich exhibition of degenerate art on July 18, 1937. This vast exhibition of 6000 works, taken from every museum in Germany, was hastily assembled. The intention was to ridicule modern art before imposing a ban on its sale. These works were deliberately shown among drawings by children or the mentally handicapped: there were two adjacent halls, with official German art hung in the first and the art identified as “degenerate” (Picasso, Braque, Matisse, Leger, Miro, Masson, Dali, Chagall) exhibited in the second. Many of the works shown in the second hall had been confiscated from museums or private galleries mainly managed by Jews. Some were intentionally destroyed, while others were auctioned for the benefit of the Nazi regime. Ironically, this attempt to ridicule modern art was to the great advantage of art lovers throughout the world. Vincent van Gogh quickly became the bestselling “degenerate” painter on the market. By the time the Reich Chamber exhibition closed on November 30, 1937, it had drawn more than two million viewers.

Joseph Goebbels, the propaganda minister, had planned the show as a counterpoint to the Great Exhibition of German Art, which opened simultaneously in Munich. It celebrated female farmers and soldiers, mothers, and rural landscape. He felt German museums had to be cleansed of works produced after 1910.

After Hitler came to power in 1933, many artists chose to go into exile. Not only could they no longer show their work or sell it, they were forbidden to buy brushes, canvases or paint.

On June 30, 1939, just weeks before the outbreak of war, the Germans held a massive auction in Lucerne, featuring 126 paintings and sculptures from the most important museums and private collections in Germany. Many collectors, unable to resist the temptation to buy outstanding works of art at low prices, attended. Rosenberg warned potential buyers that any currency the Reich harvested from this sale “would fall back on our heads in the form of bombs”. Alfred Barr, the director of the prestigious Museum of Modern Art in New York, also tried to alert those museums that had announced their intention to buy. But to no avail.

Karl Haberstock, the Nazis’ chief art buyer, became one of the Fuhrer’s personal dealers. As Haberstock began to amass a collection of old masters for Hitler, he found intermediaries in France through whom he could purge all modernist impurities. Among them was the author and Nazi apologist Lucien Rebatet, who proposed the “Aryanisation” of the fine arts.

There was a great deal of debate on this subject among Nazi officials, in particular between Goebbels and Alfred Rosenberg (Hitler’s ideological theorist, who later was placed in charge of the “occupied Eastern territories”— in other words, the massacres that took place there). This unfortunate namesake of the art dealer considered any form of physical distortion on a canvas “degenerate art”, while Goebbels believed modern painting could become part of a National Socialist revolutionary art movement. As in any totalitarian regime claiming to define a “new man” and a new world order, art was a priority for the apostles of National Socialism. Indeed, the Nazis were obsessed with the idea of turning art into an instrument of propaganda.

On June 30, 1940, Hitler issued an order to put artworks belonging to Jews in “safekeeping”. The term was chosen as a cover for what could only be described as theft. It was then that Alfred Rosenberg set up the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg. It became the chief organisation in the Nazi looting operation.

From early July 1940, the army was instructed to raid the big Parisian art dealers and seize their collections. From October 1940, organised theft followed upon random robbery. “The artworks were first assembled at the Musee du Jeu de Paume and the Louvre, then photographed, valued, recorded and wrapped ready for transport to Germany,” wrote Laurence Bertrand Dorleac. Naturally, this contraband included both the classical paintings from the Parisian galleries and modern works, which, as Dorleac put it, served as “bargaining chips for pieces more in line with the Nazi aesthetic”.

In her account, Le Front de l’art, Rose Valland, the heroic protector of French artworks, relates that at the height of the war in 1943 she witnessed a column of smoke rising from the terrace of the Tuileries; it rose from paintings stamped with the letters EK (entartete Kunst), and signed Masson, Miro, Klee, Ernst, Leger, Picasso. “The men of the ERR planned to attack these paintings, run them through with swords, slash them with knives, and carry them to the pyre, as in those gigantic autos-da-fe that had taken place in the German museums, in a bid to destroy those works identified as ‘degenerate’.”

The interior of the gallery at 21 rue La Boetie, with works by Picasso and Marie Laurencin on display.

Consistent with their plan, as soon as the Nazis occupied Paris on June 14, 1940, they made their way to 21 rue La Boetie. But they were disappointed not to find the family patiently awaiting their arrival.

On July 4, 1940, the Reich ambassador, Otto Abetz, demanded that the building on rue La Boetie be sequestered by police and that the artworks be seized. He had in fact just drawn up a list of Jewish dealers or collectors for the Gestapo: Bernheim-Jeune, Alphonse Kann, Jacques Seligmann and Paul Rosenberg.

This outrage continued with the German requisition of rue La Boetie in May 1941. On the 11th day of that month, the brand-new Institut d’Etude des Questions Juives (Institute for the Study of Jewish Questions) was installed in the building with great pomp.

I’ve examined the few existing pictures of that installation and, more particularly, I’ve listened to Radio Paris on tapes supplied by the National Sound and Video Archives. The wounding words of the speaker are unmistakably clear: “Today saw the rechristening of the building previously occupied by Rosenberg; the name alone tells you all you need to know.”

In the photographs and in the National Sound and Video Archives can be seen Louis-Ferdinand Celine, a star guest with impeccable far-right credentials, parking his bike in front of my grandfather’s gallery, on which the name of that formidable new office stands out in capital letters. The porch and the famous exhibition hall are easily recognisable. A huge panel on the wall shows a woman on the ground covered with a French flag, a vulture perched on her belly, with the caption “Frenchmen, help me!”

In the exact place where my grandfather had hung paintings by Renoir, Picasso and Leger over the previous few years, a tricolour flag, a portrait of Marshal Petain, and quotations from Edouard Drumont, the author of La France juive, who, according to commentary of the time, “first raised the issue of the Jewish problem in all its magnitude”: “The Jews came poor to a rich country. They are now the only rich people in a poor country.” And that other quote on the opposite wall: “We are fighting the Jews to give France back its true, its familiar face.”

Captain Paul Sezille was soon appointed secretary-general of the institute. A retired officer of the Foreign Legion, Sezille was, according to the historian Laurent Joly, a man drowning in booze and vitriol.

He was followed in January 1943 by the physician, anthropologist and racial theorist George Montandon, who remained in office until the last days of August 1944, just before the liberation of Paris. The institute then assumed the name Institut d’Etude des Questions Juives et Ethno-Raciales (Institute for the Study of Jewish and Ethno-Racial Questions), devoted to anti-Semitic propaganda.

In 1934, during a refurbishment of my grandfather’s gallery, Paul asked Picasso to make some marble patterns to be inlaid into the tile floor. Giving him lots of sketches in the hopes Picasso would create something unique, he first asked him for his designs in August 1928. But since Picasso never met deadlines and took a lot of persuading to carry out any commission, Paul ended up commissioning Braque to complete the project. In each of the four corners of the gallery, Braque created a rectangular marble mosaic, faithfully scaled-down copies of four of his large still lifes: pitchers, plates, lemons, cutlery and tablecloths known in his paintings.

The still lifes in question on the floor of my grandfather’s gallery were brighter, more colourful and more luminous than the works of that period. They lent themselves to mosaic treatment, recalling the designs on the floors of the patrician Roman villas in Pompeii.

After the war, when Paul sold the building he no longer wanted to live in, he had Braque’s four marble mosaics cut out of the floor and made into low tables, framed in marble. I lived alongside two of those tables throughout my youth and often stroked the marble, unaware of the innocent people, denounced and arrested, who had stepped upon them before being handed over to their executioners. The family house on rue La Boetie would have sheltered the executioners. I have never been able to watch Henri-Georges Clouzot’s masterpiece The Murderer Lives at Number 21, without thinking about that.

This is an edited extract from My Grandfather’s Gallery: A Family Memoir of Art and War by Anne Sinclair. Available August 27 through Text Publishing (288pp, $32.99).