News:

Getty Seeks to Quiet Title of the Ansouis Diptych: Back to Legal Technicalities or End of an Era?

By Emma Kleiner*

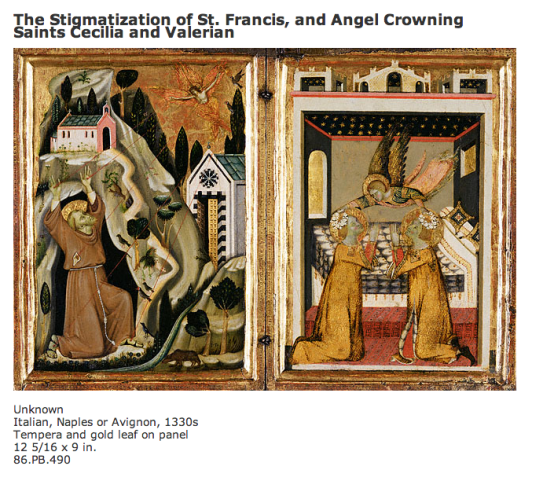

“The Stigmatization of St. Francis, and Angel Crowning Saints Cecilia and Valerian” (The Getty Museum)

Employing a popular yet controversial legal tactic, in September 2013 the J. Paul Getty Museum (Getty), represented by Munger, Tolles & Olson LLP, sued in federal court in California seeking an order to quiet title to The Stigmatization of Saint Francis and The Crowning of Saints Cecilia and Valerian. Typically, this type of action is instituted to assert a party’s title to a piece of property, thus preventing claims by others to the property. If successful, any future legal action against the Getty by Geraud Marie de Sabran-Ponteves, the heir to the original owner of the work, would be barred.

In summer 2012, the counsel for Geraud Marie de Sabran-Ponteves, a French citizen, informed the Getty that its client was claiming to be the sole owner. Defendant Geraud Marie de Sabran-Ponteves alleged the artwork belongs to him as a component of a “long-running inheritance dispute”— a claim that the Getty asserts is erroneous. This lawsuit may be a test case for resuscitating technical defenses museums use seeking to keep works with disputed histories within their collections. Legal arguments like these are based on technicalities rather than the merits of a case, and the use of such arguments has a divisive history in the context of art title disputes.

For three decades, the Getty has prized The Stigmatization of Saint Francis and The Crowning of Saints Cecilia and Valerian, also known as the Ansouis Diptych, for being “a beautiful and well-preserved and devotional object” and “[u]nique in subject.”The Ansouis Diptych, currently valued at approximately $2.7 million, has been alternately attributed to a late fourteenth century Avignon painter and to an early fourteenth century Naples painter. The Getty purchased this work in 1986 from the Wildenstein & Company gallery, which in turn had purchased it five years earlier from the Sabran-Ponteves family. The Sabran-Ponteves family owned the Ansouis Diptych for generations. In fact, the work is traditionally interpreted as featuring Sabran-Ponteves’ ancestors in one of the panels. Geraud Marie de Sabran-Ponteves asserts that the sale of the artwork to the Wildenstein & Company gallery was unauthorized because the seller, his brother Charles Elzéar, offered it to the gallery without acquiring the consent of the other four siblings.

The Getty, however, is seeking an order to quiet title based on its purchase of the work in good faith and its display of the artwork prior to any legal claims arising. Furthermore, the Getty asserts that Geraud Marie de Sabran-Ponteves’ claims are barred by California’s statute of limitations. According to the Getty, Sabran-Ponteves was aware of the artwork’s location as early as 1987; he even contacted the Getty staff in 1999 about the artwork for the purpose of valuing his family’s estate. To sue in California within the statute of limitations, Sabran-Ponteves needed to bring suit within three to six years of locating the artwork, which he failed to do. In the alternative, the Getty asserts that it owns the artwork by adverse possession.

The tendency for a museum to seek an order to quiet title to an artwork, and the success of doing so in terms of outcome and public opinion, has waxed and waned over the last decade. It is informative to look at how museums have approached similar disputes regarding Holocaust-era assets because the legal techniques discussed above are frequently utilized in such lawsuits. For instance, in 2006 the Toledo Museum of Art filed suit to quiet title of Street Scene in Tahiti by Gaugin. Similarly, in 2006 the Detroit Institute of Art filed suit to quiet title of The Diggers by Van Gogh. In 2008 the Museum of Modern Art and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation filed suit to affirm their respective ownership of Boy Leading a Horse by Picasso and Le Moulin de la Galette by Picasso on the basis that the original owners voluntarily sold the artworks. In 2009 the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston invoked the statute of limitations to affirm ownership of Two Nudes (Lovers) by Kokoschka, and the matter was resolved without reaching the merits of the case. Finally, in 2011, the Museum of Modern Art used a similar argument to affirm ownership of three works by Grosz. The tactical decision to use actions to quiet title and invoke statutes of limitations is readily seen through these examples, as in the dispute with Sabran-Ponteves.

Many museums, including those mentioned above, have received harsh criticism for opting for preemptive legal measures to settle title disputes, instead of conducting provenance research prior to the acquisition of the artwork or working with the individuals claiming rightful ownership of artwork. For example, Charles Goldstein and Yael Weitz, of Herrick, Feinstein LLP (NYC), write: “[M]useums, as institutions that function in a climate of ethical responsibilities, owe a duty to the public to maintain the integrity of their institutions,” which includes allowing for cases involving artworks with disputed histories to be litigated on the merits. Still, other scholars and practitioners argue that actions seeking to quiet title of artwork or actions based upon statutes of limitations are appropriate. For example, not all claims made by heirs of the former owners of artwork are meritorious, and such ought to be dismissed at an early stage of the dispute both to conserve museum resources and reduce the court docket. Furthermore, museums have the obligation to “take all reasonable steps to protect the assets they hold in trust,” including bringing suit to quiet title or invoking statutes of limitations. While scholars often times focus the discussion around Holocaust-era asset lawsuits, this debate readily reaches all situations in which a museum attempts to argue the technicalities rather than the merits of a case.

The controversy surrounding filing suit to quiet title and invoking statutes of limitations continues to influence the manner in which a museum chooses to claim ownership of contested works. In this case, the Getty already holds a controversial reputation due to its past legal problems and public repatriation battles. Now, the Getty took a public relations gamble in attempting to utilize the legal system to bar Sabran-Ponteves from bringing suit against it. Thus the anticipated resolution of this lawsuit by Judge Gary Feess may shed light on whether these legal tactics will continue to be favored or disfavored by museums.

Sources:

- J Paul Getty Trust et al v. Geraud Marie De Sabran-Ponteves, Complaint, 2:2013cv06561 (Cal. Sep. 6 2013)

- Laura Gilbert, These saints are ours, Getty says, The Art Newspaper (Sept. 18, 2013), http://www.theartnewspaper.com/articles/These-saints-are-ours-Getty-says/30444.

- Ricardo A. St. Hilaire, Getty Mounts Preemptive Legal Strike: Museum Seeks to Quiet Title of 14th Century Ansouis Diptych, Cultural Heritage Lawyer Rick St. Hilaire (Sept. 16, 2013), http://culturalheritagelawyerblogspot.com/2013/09/getty-mounts-preemptive-legal-strike.html.

- The J. Paul Getty Museum, Acquisitions 1986, 15 The J. Paul Getty Museum Journal 153, 155 (1987), available at http://books.google.com/books?id=mm4mAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA184&lpg=PA184&dq=Ansouis+Diptych&source=bl&ots=R3riCsw5RY&sig=dLbIpYipGnbjW5UolK5uGWhF3Jg&hl=en&sa=X&ei=I240U8LmApDlqAGQ7IHAAw&ved=0CEoQ6AEwBw#v=onepage&q=Ansouis%20Diptych&f=false.

- Jennifer Anglim Kreder, U.S. Museums’ Use of Declaratory Judgment Actions in Nazi-Looted Art Disputes, Art, Cultural Institutions and Heritage Law Newsletter (International Bar Association Legal Practice, London, England), October 2007, at 7, available at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=999666.

- Lindsay Pollock and Philip Boroff, Judge Slams MoMA, Guggenheim on Secret Holocaust Art Agreement, Bloomberg (June 18, 2009), http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=newsarchive&sid=ayZK6G30lMfU.

- US Court of Appeals Confirms Museum of Fine Arts, Boston is Rightful Owner of Oskar Kokoschka’s Painting Two Nudes (Lovers), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (Oct. 15, 2010), https://www.mfa.org/news/press-releases/10-15-2010.

- Nina Burleigh, Haunting MoMA: The Forgotten Story of ‘Degenerate’ Dealer Alfred Flechtheim, Gallerist (Feb. 14, 2012, 7:04 PM), http://galleristny.com/2012/02/haunting-moma-the-forgotten-story-of-degenerate-dealer-alfred-flechtheim.

- Museum Ethics: Best Practices and Real Events, Commission for Art Recovery, http://www.commartrecovery.org/content/museum-ethics-best-practices-and-real-events (last visited March 28, 2014).

- Charles A. Goldstein and Yael Weitz, Claim by Museums of Public Trusteeship and Their Response to Restitution Claims, Art & Advocacy (Herrick, Feinstein LLP, New York, N.Y.), Winter 2013, at 4, available at http://www.herrick.com/siteFiles/Publications/6137C37224EAB288C8B77989C56A543F.pdf.

- Simon Frankel and Ethan Forrest, Museums’ Initiation of Declaratory Judgment Actions and Assertion of Statutes of Limitations in Response to Nazi-Era Art Restitution Claims — A Defense, 23 DePaul Journal of Art, Technology & Intellectual Property Law 279, 280 (2013), available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=2363607.

- Former Getty curator Marion True was accused of stealing antiquities and was on trial in Rome for five years before the case was dismissed in 2010. Hugh Eakin, Marion True on Her Trial and Ordeal, The New Yorker (Oct. 14, 2010), http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/newsdesk/2010/10/marion-true.html. The Getty returned two objects to Greece while Marion True on trial in Rome. Neda Ulaby, Getty Museum to Return Greek Artifacts, National Public Radio (July 10, 2006), http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5546815. The Getty returned forty objects to Italy in 2011 after years of deadlocked negotiations. Laura Sydell, Getty Museum Strikes Deal to Surrender Antiquities, National Public Radio (Aug. 1, 2007), http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=12428709.