News:

Hermann Göring's art collection goes online

By Alan Nothnagle

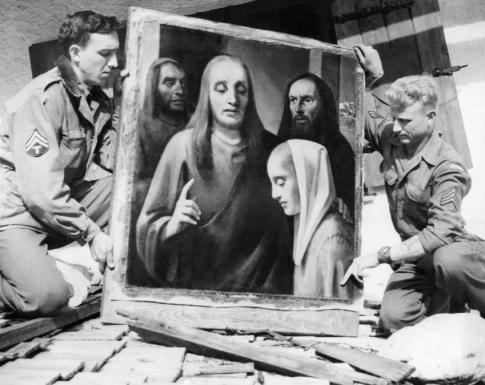

US troops unpack Jan Vermeer's purported "Christ and the Adulteress" in 1945. This painting was actually a clever forgery by a Dutch counterfeiter, who sold it to Göring as the real thing in 1942.

HERMANN WILHELM GÖRING, A demobilized World War I flying ace and last commander of the famed Von Richthofen Squadron, wore many hats during Hitler’s “Thousand-Year Reich”: Early cheerleader, commander of the Storm Troopers, founder of the Gestapo, crusher of all opposition, creator of the Reich’s modern Luftwaffe, master of the Four-Year Plan, overseer of the vast Hermann Göring Works, Reich Hunting Master, and the man in charge of commissioning a “total solution of the Jewish problem.” In the world of culture, however, Göring is remembered as one of the greatest art collectors and art thieves in history. This week, the German Historical Museum, the German Federal Archive, and the Federal Agency for Central Services and Open Property Issues (BADV) are placing his vast collection of bought and pilfered artwork online for the world to examine and, whenever possible, identify.

Pilot Göring in 1918 with the coveted "Pour le Mérite" or "Blue Max" medal around his neck

Göring is frequently quoted as having said: "Whenever I hear the word culture I reach for my revolver." (This is actually a line from Hanns Johst's Nazi-era play Schlageter.) But while he certainly acted like a barbarian in many ways, Göring was simultaneously a classic esthete and a passionate collector of artworks and beautiful objects. Upon joining the Reichstag for the Nazi Party in 1928, which provided the unemployed pilot with a regular income, Göring began purchasing artwork on the open market. After the Nazi seizure of power brought him the titles of Prussian Prime Minister and Interior Minister in addition to that of President of the Reichstag, he sped up his collecting activities in order to furnish the extensive real estate he was purchasing. As he tightened his control over society, Göring increasingly resorted to confiscating valuable works from Jewish families and other supposed enemies of the regime. When war broke out he set up a commission that systematically combed the occupied territories for new trophies. He and his staff collected thousands of works, including some 1,800 paintings. Many of these objects, particularly from the medieval and renaissance eras, ended up on the walls and in the display cases of Göring’s lavish Carinhall palace in the Schorfheide forest district north of Berlin, which he planned to develop into a full-blown public “North German Gallery.” It was the largest collection in the Third Reich after Hitler’s immense plundered treasure trove for the planned post-victory “Führermuseum” in Linz.

The great hall of Göring's Carinhall palace, which he named in honor of his first wife, a Swede. The Reich Marshall ordered the complex to be obliterated using 80 aerial bombs in the final days of the war.

After Germany’s defeat and Göring’s capture and later suicide, the collection, since evacuated to Bavaria, fell into the hands of the US Army, which began working with German authorities to restore it to its legal owners. The German government assumed complete control over the items in 1949. According to a proclamation issued in London in 1943, all deeds of sale generated in the occupied countries, where the works were often sold to Göring’s art team for a pittance, were declared null and void. A small number of articles were eventually returned to Göring’s widow Emmy to the extent that they were clearly family property and not extorted or stolen from anyone else.

Göring's mugshot

Piece by piece, the looted objects returned to their purported owners across Europe. Then in 1998, the Washington Declaration on Nazi-Confiscated Art called for public institutions in forty-four countries, including Germany, to reexamine their art inventories. Specifically,

In establishing that a work of art had been confiscated by the Nazis and not subsequently restituted, consideration should be given to unavoidable gaps or ambiguities in the provenance in light of the passage of time and the circumstances of the Holocaust era.

Every effort should be made to publicize art that is found to have been confiscated by the Nazis and not subsequently restituted in order to locate its pre-War owners or their heirs.

Even though most of the works in Göring’s collection have been restored to private persons and public art galleries, the legal situation is extremely complex. For example, many wealthy Jewish families had to liquidate their art collections in a hurry. These works then passed through a number of hands before ending up in Carinhall. Who really owned them then, and who owns them now? And how many artworks currently on display in public museums once passed through the Reich Marshal's hands? Added to this, many of the objects were plundered after Göring had the entire collection shipped down to Berchtesgaden in three special trains during the last days of the war. Assuming that some of these works are still hanging on private citizens’ walls or in local galleries, who actually owns them?

These are just some of the questions the new online catalogue is designed to help answer. It brings together 4,263 items that Göring’s own art staff catalogued for eventual display purposes after the Reich’s victory. The original black and white photos scarcely do justice to the beauty of the original objects. Say what you want about the bloated, manic, morphium-crazed Reich Marshal, but when it came to renaissance and medieval art, the man had a very keen eye indeed.

And by the way: If anything in this catalogue resembles that old heirloom hanging on your living room wall, you might drop the German Historical Museum a line…

Mary with Jesus and John the Baptist by Botticelli

Portrait of an Old Man by Rembrandt

Sketch of a Stag Beetle by Albrecht Dürer

Suicide of Lucretia Borgia by Lucas Cranach the Elder

The Birth of Christ by Allessandro Moretta da Brescia

A Gobelin tapestry

This painting by Picasso shows a rare deviation from Göring's usual taste, since such "degenerate" art normally landed either on the international art market to earn much needed foreign currency, or else on a bonfire