News:

The Nazis didn't just burn Jewish books - they stole millions, too

Haaretz 20 April 2017

By Rafael Medoff

Nazi ideologue Alfred Rosenberg.

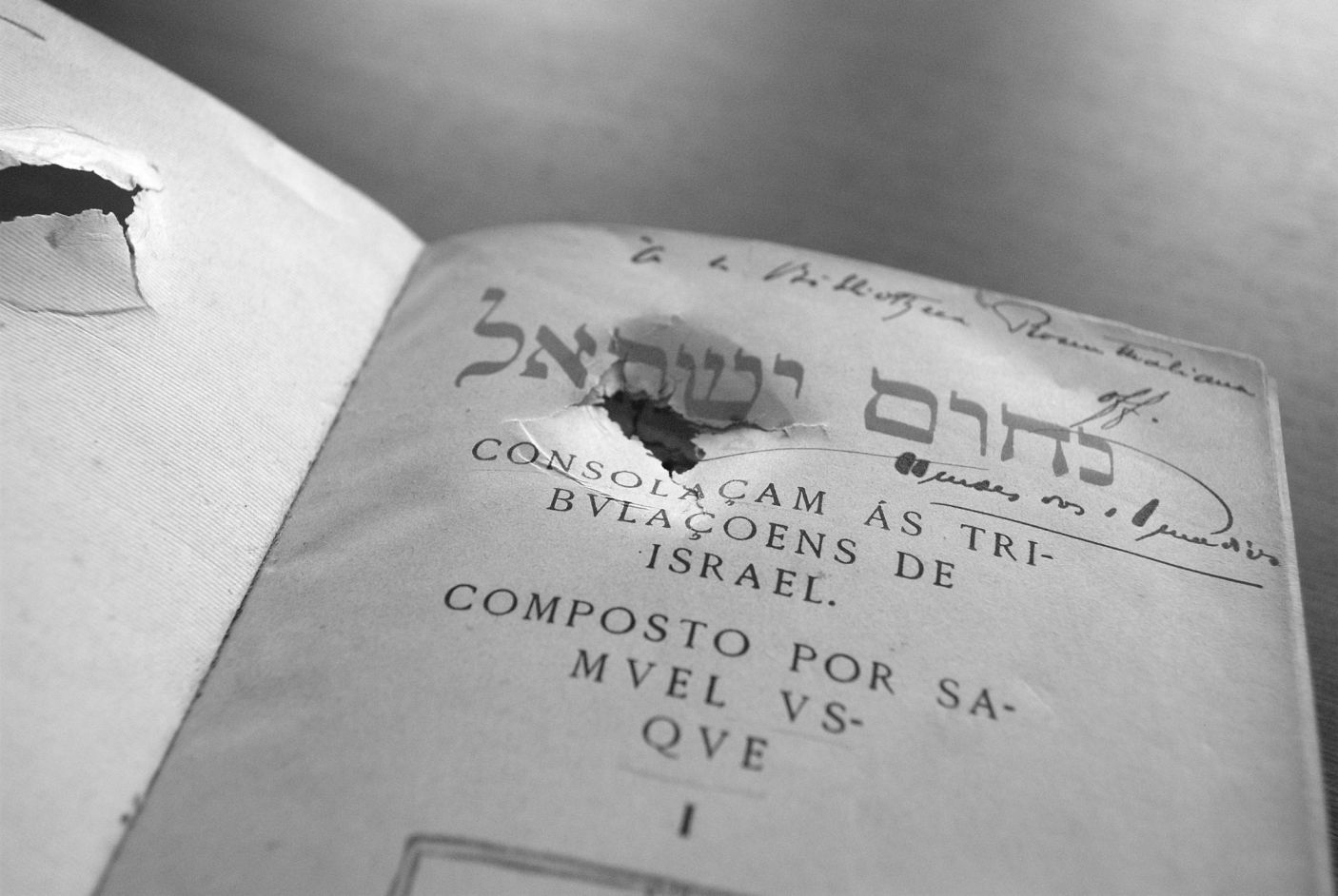

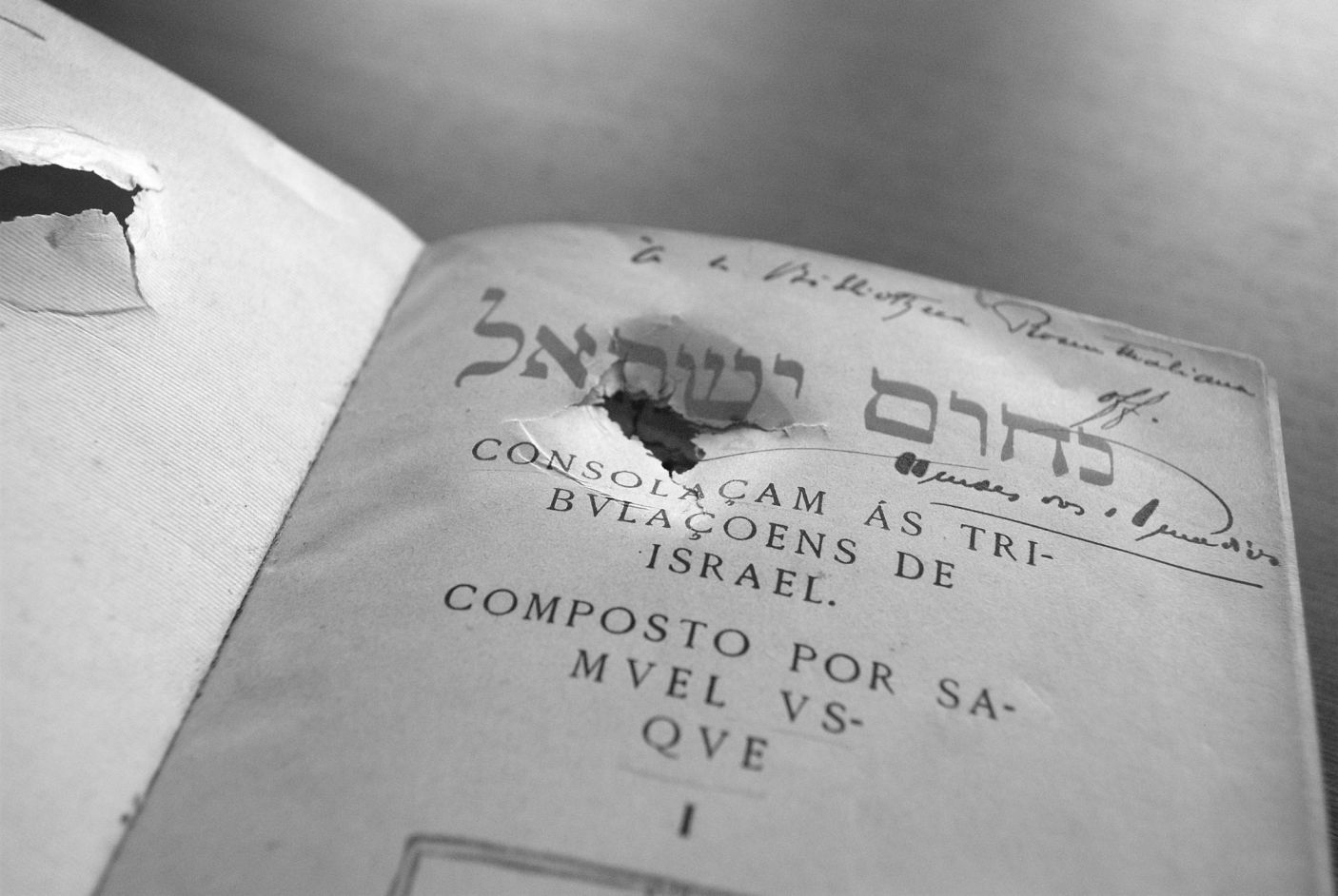

The mysterious bullet-damaged book at the Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana, Samuel Usque’s “Consolation for the Tribulations of Israel”. The bullet is believed to have been fired in Germany.

Books at the Jewish Museum in Prague, originally with the Talmudkommando in Theresienstadt. The books still carry the markings made by the camp prisoners.

By Rafael Medoff

In 'The Book Thieves,' author Anders Rydell explains the Nazis' aim: to assert complete control over public information and literature, and utilize them to advance Hitler’s ideological goals.

“The Book Thieves: The Nazi Looting of Europe’s Libraries and the Race to Return a Literary Inheritance,” by Anders Rydell (translated by Henning Koch), Viking Press, 352 pp., $28

Images of Nazis burning books feature prominently in almost every account of the Hitler era. But Swedish journalist Anders Rydell shows in “The Book Thieves” that the Nazis were actually much more interested in stealing books than destroying them.

Berlin’s central library, the Zentral und Landesbibliothek, boasts an impressive collection of thousands of bookplates that were cut out of books over the years, usually when the books were taken out of circulation. Around 15 years ago, a librarian named Detlef Bockenkamm noticed that hundreds of the bookplates bore Jewish names or symbols. His suspicions about their provenance led to the discovery that a significant number of books in the library were originally stolen from others by the Nazis.

Not only were some of Bockenkamm’s predecessors on the library staff aware that the books were purloined, but they even “tore out or scraped off” evidence of the original owners’ identity and “catalogued [the books] with forged origins…all to make them blend into the collection,” Rydell reports.

Meanwhile, at the famous Duchess Anna Amalia Library, in Weimar, a different set of circumstances raised questions about the origins of some of their holdings. After a fire in 2004, the staff decided to re-catalogue the entire collection to determine the extent of their losses. In the process, they came to realize that some of the books had been acquired in less than honorable ways.

Nazi ideologue Alfred Rosenberg.

Chance developments such as these began the untangling of a sordid but little-known chapter in the history of the Third Reich. Millions of books were seized as part of a coordinated strategy, under the guidance of Nazi ideologue Alfred Rosenberg, to plunder libraries throughout occupied Europe. The goal was to assert complete control over public information and literature, and utilize them to advance Hitler’s ideological goals. The looting was so vast and the chances of locating the books’ rightful owners so remote, that justice will never be done except in a handful of cases.

In this fast-paced and well-written account, Rydell describes how the Germans plundered major public and private libraries in every country they occupied during World War II. In occupied France, for example, they seized more than 1.7 million books from the larger libraries alone. That figure grew considerably when the Nazis began looting private apartments of Jews who fled or were deported. The contents of some 29,000 such apartments in Paris alone were seized.

The collections held by Freemason lodges were of particular interest to the Nazis, both because they were known to maintain formidable libraries (a consequence of the fraternal order’s intellectual inclinations) and because the Nazis viewed Freemasons as Jewish-controlled. That was an ironic accusation since it was not until the mid-19th century that Jews even were permitted to join masonic lodges. In the Netherlands, the Germans confiscated several hundred thousand books from Freemasons, according to Rydell.

Poland was not treated the same, in this regard, as Western Europe. The Nazis regarded the French, Belgians, Dutch and Scandinavians as fellow-Aryans. They stole rare and valuable books from their public institutions, and from local Jews, Freemasons and political enemies, but not from private homes in general; the goal there was not to destroy the local culture. The Poles, however, were considered racially inferior Slavs who needed to be completely subjugated. Therefore, the Germans’ strategy was “to rob the Poles of all forms of higher culture, learning, literature, and education.” Between two and three million books were stolen from Poland, and another 15 million were destroyed.

When the Germans occupied western Russia, they found that the Soviet authorities had preceded them in book-stealing. Political and social dissidents, including the Freemasons, had been outlawed by Moscow, and Jewish schools and libraries had been shut down long ago and their property confiscated. The Nazi book thieves did, however, acquire a major prize by seizing the books and archives of Communist Party institutions in the USSR. In the city of Minsk alone, the holdings of just the Lenin Library filled 17 railroad cars, Rydell reports. The Communist Party’s records for the Smolensk Oblast region occupied no less than 1,500 shelf-yards.

The mysterious bullet-damaged book at the Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana, Samuel Usque’s “Consolation for the Tribulations of Israel”. The bullet is believed to have been fired in Germany.

Jewish books and manuscripts were of special interest to Rosenberg, because he believed they would reveal damning information about international Jewish conspiracies. Public and private libraries in every Jewish community the Germans overran were ransacked. A small portion of the loot was sent to Theresienstadt, the “model ghetto,” where a library was created to serve as a prop to impress Red Cross visitors.

At its peak, in 1944, the Theresienstadt library held some 120,000 books, according to Rydell. The number declined when prisoners were deported from Theresienstadt to Auschwitz; the deportees often took several of their favorite books with them, and the librarians did not try to persuade them that there would be no need for books where they were going.

“The SS did not limit itself to stealing books…it also stole human beings,” Rydell reports. Since they could not understand Hebrew or Yiddish, the Germans kidnapped Jewish scholars and put them to work separating valuable Jewish works from those for which the Nazis had no use. The enslaved scholars were anguished at the thought that “they would be contributing to research which would fundamentally have the intention of justifying the Holocaust,” Rydell notes, but the alternative “was hardly any better, because books that were not selected were sent to a nearby paper mill, where they were pulped.” One of the captive scholars wrote in his diary: “I do not know if we are redeemers or gravediggers.”

The work of this forty-man group, which called itself the Paper Brigade, took place in the Vilna Ghetto, which during 1942-’43 was used by the Germans as a collection point and sorting station for stolen books. Thebrigade members managed to occasionally salvage literary treasures by hiding them in their clothes. In this way, they rescued Theodor Herzl’s diary, illustrations by Marc Chagall and original manuscripts by the Vilna Gaon and Tolstoy.

When Allied bombing raids endangered stolen-book depots in Berlin, the Germans set up a new collection area at Theresienstadt. The “Talmudkommando,” a group of Jewish scholars similar to the Paper Brigade, was tasked with sorting newly arrived materials. They had selected and catalogued about 30,000 volumes by the time the Germans fled Theresienstadt in April 1945.

Books at the Jewish Museum in Prague, originally with the Talmudkommando in Theresienstadt. The books still carry the markings made by the camp prisoners.

As the Red Army advanced into previously German territory at war’s end, Stalin sent along representatives of his Special Committee for War Reparations. In Stalin’s view, the most appropriate form of reparations would be to match Hitler’s book-stealing with some grand larceny of his own. According to Rydell, “in 1945 alone, some 400,000 railroad cars of plundered goods were sent to the Soviet Union.” Some of it, of course, was reclaimed Soviet property. But much of it was not.

These Soviet “trophy brigades,” as they were informally known, included special library units. “The Lenin Library in Moscow ended up as the largest single recipient of trophy books, almost two million all told,” Rydell writes. He calculates that the trophy brigades confiscated a total of between 10 and 11 million books. That figure does not include books stolen by other government divisions or Red Army soldiers, among others.

Institutions that were victimized by the Germans later in the war stood the best chance of getting their property back. The collections of two famous Jewish libraries in Amsterdam, Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana and Ets Haim (the oldest functioning Jewish library in the world), were rescued because their holdings were still in crates when the Allies arrived; the Germans had not yet got around to processing them.

“But the Western Allies are not entirely innocent themselves,” Rydell notes. “Almost a million books were sent to the Library of Congress in Washington. Several large American libraries sent delegations to Europe to top up their collections.”

There is little hope that any more than a tiny portion of the looted books will ever be returned to their original owners, given the extent to which such books have blended into larger collections, and the paucity of information that even well-intentioned libraries possess about the books’ individual origins. Still, the efforts by the aforementioned Detlef Bockenkamm and other librarians to return at least some of them deserve our admiration.

Rydell relates the story of Bergen-Belsen survivor Walter Lachman, who identified one of his childhood books from a description in an article in Der Spiegel about the Nazi book thefts. Lachman’s daughter, who traveled to Germany from California to retrieve the book, said that her father “had never really spoken about the past, but this changed once he got the book back. It brought him out of himself and he started telling his story. Now he is giving talks in schools, to children.” If that reclaimed book results in educating even a few children about the Holocaust, then at least a tiny measure of justice will have been attained.

http://www.haaretz.com/life/books/.premium-1.784169© website copyright Central Registry 2024