News:

Cleveland Museum of Art returns ancient Roman portrait of Drusus after learning it was stolen from Italy in WWII

By Steven Litt

CLEVELAND, Ohio - The Cleveland Museum of Art and the government of Italy announced Tuesday that the museum would return to Italy an ancient Roman marble portrait head of Drusus Minor after learning that it apparently had been stolen in 1944 from a provincial museum near Naples.

The museum removed the head from Gallery 103 on Monday and is preparing to ship it back to Italy, said William Griswold, the museum's director.

"It is disappointing, even devastating, to lose a great object," he said. "On the other hand, the transfer of this object to Italy is so clearly the appropriate outcome that, disappointed though I may be, one can hardly question whether this is the right thing to do."

The joint statement quoted Dario Franceschini, Italy's minister of fine arts, as saying the return of the Drusus "is the result of an important and fruitful cultural agreement and the full cooperation of CMA with the Italian authorities."

Mistaken faith in title

When it bought the Drusus in 2012 for an undisclosed amount from Phoenix Ancient Art, the museum believed it had clear title, and that the work had been in an Algerian collection as far back as the late 19th century.

The museum and its Italian counterparts now believe that Italian archaeologists excavated the Drusus head in 1925 or 1926 in Sessa Aurunca, in the Caserta Province of Campania, Italy, about an hour's drive north of Naples.

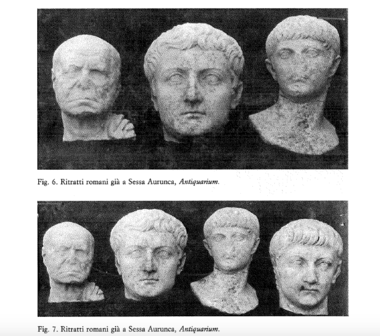

The archaeologists had the Drusus photographed at the time, along with other discoveries including a marble portrait head of the Roman Emperor Tiberius, father of Drusus Minor.

A 1926 photo taken around the time of an excavation in Sessa Aurunca, Italy, documented the discovery of the portrait head of Drusus Minor, lower right, that eventually ended up in the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art. The museum is returning the sculpture to Italy after learning it was stolen from Sessa Aurunca's museum in 1944.Courtesy Ministero dei Beni e Delle Attivita Culturali del Turismo

The works were also placed in the archaeological museum at Sessa Aurunca, where they remained until they were removed in 1944.

Given that evidence, Griswold said, the museum and Italy now view the Drusus portrait as having been stolen.

It also does not fall into the category of works looted by tomb robbers from previously unknown sites in violation of the 1970 UNESCO convention aimed at halting illegal excavation and trafficking of antiquities.

In 2008, the museum returned 13 such looted antiquities to Italy, plus a 14th object, a processional cross that was stolen from a church near Siena. The Drusus falls in the same category as the cross, not the 13 other objects, Griswold said.

Big impact on collection

For the past five years, the Drusus helped anchor the museum gallery devoted to the height of the Roman Empire. The sculpture is notable for its luminous white surfaces, supple carving and for the powerful gaze of its subject.

The museum believes the work was made after the death of Drusus in 23 A.D., when his wife, Claudia Livia Julia, known as "Livilla" or "Little Livia," allegedly poisoned him at age 34.

Drusus was the heir apparent to Tiberius, but he disturbed Rome with his enjoyment of blood sport and ritual killing, the museum said on its website.

Purchase criticized immediately in 2012

The museum's purchase of the Drusus portrait in 2012 earned instant criticism from experts including archaeology Professor David Gill at the University of Suffolk in Ipswich, England. He and others complained of gaps in the provenance, or ownership history, of the object.

The museum believed at the time that the portrait had been the property of the Bacri family (later known as the Sintes family) of Algiers, Algeria, as far back as the late 19th century.

The museum said in 2012 that Fernand Sintes and his wife, then of Marseilles, France, inherited the work while living in Algiers. They subsequently moved it with them to Marseilles in 1960.

Fernand Sintes subsequently sold the Drusus at an auction at the Hotel Drouot in Paris in 2004 to an unnamed buyer. A day later, Parisian art dealer Jean-Philippe Mariaud de Serres, who advised Sintes on the auction, provided a "certificate of origin" for the work that included the Bacri-Sintes history.

That document and independent research carried out by the museum later buttressed its faith in its 2012 purchase.

No record of export from Algeria

Yet Franklin said in 2012 that because Algeria was a French possession in 1960, no export documentation was required for the Drusus. As a result, no record of the transfer from Algeria to France exists.

The museum also didn't know who owned the work between 2004 and 2012.

The purchase raised additional suspicions because the principals of Phoenix Ancient Art, brothers Ali and Hicham Aboutaam, with offices in New York and Geneva, Switzerland, had had brushes with the law.

Ali Aboutaam was sentenced in absentia in Egypt in 2004 on charges of smuggling and sentenced to 15 years in prison. Ali Aboutaam's lawyer, Mario Roberty, said at the time that the charges were "absolutely ridiculous" and politically motivated.

Hicham Aboutaam pleaded guilty in New York in June 2004 to a misdemeanor federal charge that he had falsified a customs document to hide the origins of an ancient silver drinking vessel the Phoenix gallery later sold for $950,000.

In 2004, the Aboutaams also sold a large bronze statue of Apollo to the Cleveland museum, which it believes is an original work by Praxiteles, one of the greatest masters of ancient Greek art.

Like the Drusus, the Apollo also has gaps in its ownership history, but the museum believes its title is clear.

Lingering doubts

Despite its high confidence about the Drusus, the Cleveland museum posted a description of it on the "Object Registry" of the Association of Art Museum Directors, a global online clearinghouse for objects whose provenance is not entirely known.

According to the AAMD write-up, the Cleveland museum contacted Fernand Sintes who reconfirmed everything stated in the 2004 certificate of origin authored by de Serres.

Subsequent research by Michael Bennett, the museum's curator of ancient Greek and Roman art, and by scholars and government authorities working independently in Italy, began to raise doubts, however.

Articles published in Italian archaeological magazines in 2011 and 2013 by scholars Giuseppe Scarpati and Sergio Cascella, respectively, reproduced the previously unpublished 1926 photographs taken when the Drusus and Tiberius heads were first unearthed.

Those articles suggested that both pieces had been stolen from the local museum in 1944.

Repatriation requested in 2014

A third article by Scarpati in 2014, in the Bolletino D'Arte, or Art Bulletin, mentioned the Cleveland museum's purchase of the work, and urged that it be returned to Italy.

Scarpati conjectured that the Drusus and Tiberius heads were "trafficked" by French occupation troops in 1944 while they were billeted at the museum in Sessa Aurunca.

He also suggested that the works might have fallen into the hands of North African troops active in the area at the time, perhaps explaining the later appearance of the Drusus in Algeria.

Griswold said the Cleveland museum contacted Italy's Ministry of Fine Arts in late 2016 and proposed collaborating on further research on the Drusus sculpture that also involved the Carabinieri.

"We were able to establish to our satisfaction that the [Drusus] head is the same as the one in the [1926] photograph, and the head in the photograph was in all likelihood removed from the museum at Sessa Aurunca,'' he said.

No blaming

Griswold said that the museum isn't pointing fingers at Fernand Sintes or at Phoenix Ancient Art.

"There's a gap [in the Drusus provenance] from 1944 until the 1960s, when the object was in France," Griswold said.

"We have every reason to believe it was in Algeria through the '50s, but that's not fully documented."

Griswold declined to comment on whether the museum would be reimbursed by Phoenix.

"Although we do customarily require dealers to warrant good title to any object that we purchase from them, we don't comment on the details of private transactions, and so I'm not going to do that now," he said.