News:

Dr. Oetker is Showing the World What to Do With Nazi Looted Art

By Isaac Kaplan

Anthony van Dyck, Portrait of Adriaen Moens, 1628

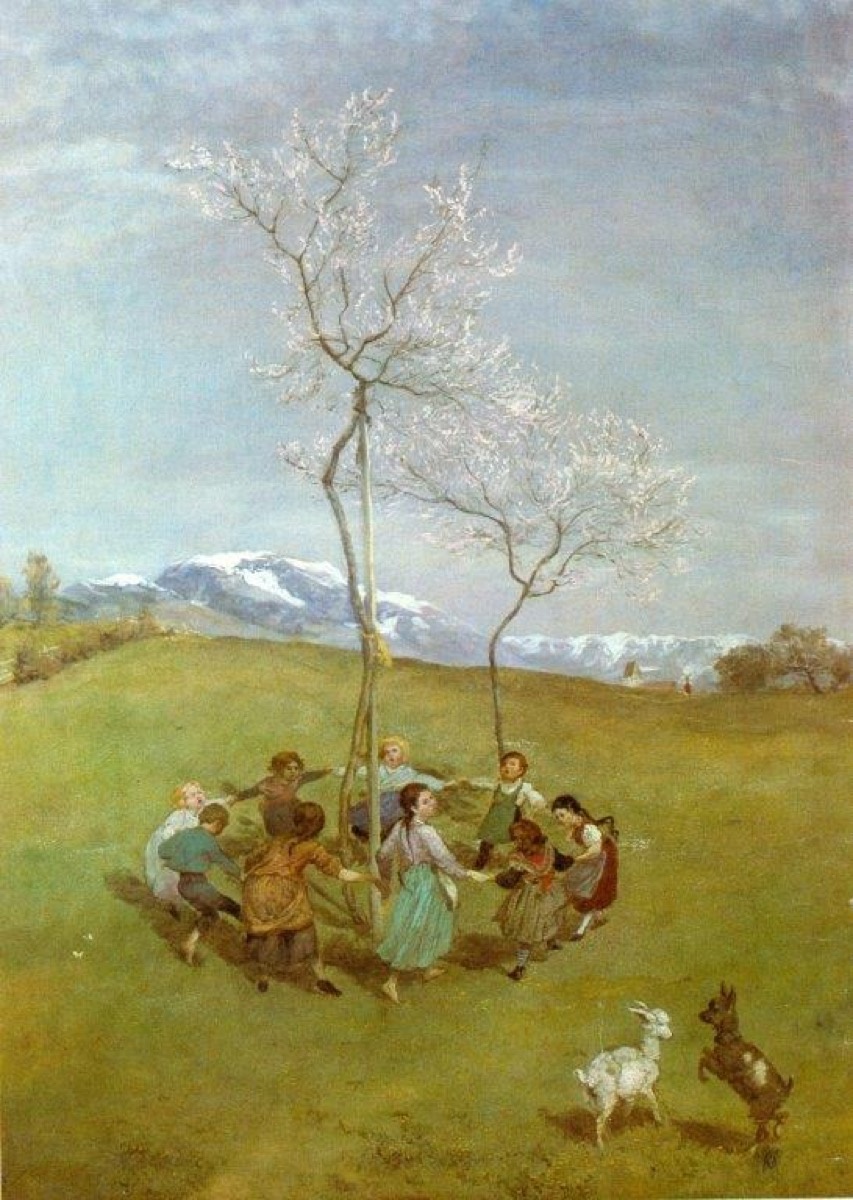

Hans Thoma, Frühling im Gebirge/Kinderreigen,

1874–75

Dr. Oetker is world-renowned for its frozen pizzas. But the German food corporation’s Oetker Collection (Kunstsammlung Rudolf-August Oetker GmbH) also owns hundreds of works of art, which are largely kept from public view. Now, the collection is engaging in a systematic campaign to determine which of the pieces it holds were looted or expropriated by the Nazi regime—and to return those looted artworks to their rightful heirs.

The voluntary effort, aimed at achieving a morally just outcome, contrasts with how many restitutions of Nazi-looted art come about and receive public attention. Museums are more often dragged to court by heirs who have themselves discovered a piece of looted art in the museum’s collection. They then just as often rely on technical legal defenses as opposed to addressing the factual substance of a given claim. Other private collections work to research the provenance of the works they hold. But, unlike Dr. Oetker, the research and findings are usually kept quiet in order to avoid attention.

“I really do think it is, unfortunately, exceptional,” David J. Rowland said of Dr. Oetker’s efforts. A partner at Rowland & Petroff, Rowland represented the rightful heirs to a Hans Thoma painting restituted by the Oetker Collection in January.

“It’s an example of how things should be done,” he said.

Research into the Oetker Collection began in the spring of 2015, with the hiring of a team of researchers to investigate the provenance of its holdings. It followed a more global research initiative into the family-owned company’s history, which detailed Dr. Oetker’s close relationship to Hitler’s regime, one similar to those of many major companies in Germany that operated during the Second World War.

While serving as the company’s chief executive, Richard Kaselowsky joined the National Socialist party in 1933. Rudolf-August Oetker, the grandson of the company’s founder who was responsible for assembling a majority of the Oetker Collection, was a volunteer for Waffen-SS and trained at the Dachau concentration camp before becoming president of the company in 1944. And Kochs Adler, a company majority-owned by the Oetker family, produced munitions for the Third Reich and also employed forced labor.

The Thoma painting restituted to Rowland’s clients, Frühling im Gebirge/Kinderreigen (1874–75), was purchased at auction by Rudolf-August in 1954. Decades before going under the hammer, however, the work belonged to Albert and Hedwig Ullmann, a Jewish couple living in Germany. Albert Ullmann had passed away in 1912, and Hedwig Ullmann was forced to sell the painting before fleeing Germany to avoid Nazi persecution in 1938.

Heirs of the Ullmanns listed the work on the German government sanctioned Lost Art Internet Database. In the course of investigating the Oetker collection, provenance researchers matched their Thoma painting with the piece listed online and contacted the Ullmann heirs in 2016. The two parties came to a final settlement in January.

The restitution came quickly after the company announcement in October of last year that it had found four works in its collection, including the Thoma, that were possibly looted by the Nazis or sold under duress. Along with Frühling im Gebirge/Kinderreigen (1874–75), Anthony van Dyck’s Portrait of Adriaen Moens (1628) has also since been returned to the heirs of its original owners. (In the van Dyck case, the heir, Marei von Saher, contacted the Oetker Collection.) The company’s investigations and restitution efforts are ongoing.

By any reasonable estimate, Dr. Oetker’s systematic provenance research comes at a financially significant cost. For provenance research broadly, the time and expense required depend on the specifics of the piece being investigated, including the availability of records pertaining to its history.

A search of the handful of reliable databases that catalogue looted artworks—to see if a piece has been listed as looted—can be performed with relative speed. But a work being listed generally requires heirs or other entities to know that it is missing in the first place and to have reported it as such. More difficult provenance research into a painting that crossed war-torn Europe, for example, can cost tens of thousands of dollars and take more than a year.

For museums looking to research vast collections of potentially looted art, the time and expenditure can be daunting and fiscally impossible in some cases. Only a handful of major institutions or state collections have dedicated provenance researchers actively looking into the work they hold.

And even still, spending money on provenance research efforts doesn’t guarantee success. A specially commissioned task force researching works of suspicious provenance among the over 1,200 pieces found in the Munich apartment of Cornelius Gurlitt cost the taxpayers €1.8 million ($1.9 million) over two years. In that time, it uncovered the rightful owners of just five works of art.

Efforts to research the Oetker Collection appear relatively more successful, according to those I spoke with. And that it has worked amicably with heirs is of note to outside observers used to more contentious negotiations with institutions.

“Museums could learn a lot from this,” said Nicholas O’Donnell, a partner at Boston law firm Sullivan & Worcester who is currently litigating ongoing Holocaust restitution suits. O’Donnell is critical of how some institutions deploy what he calls “scorched earth” legal defenses—engaging in protracted arguments over statutory aspects of a case to prevent arguing on the basis of the historical facts, for example.

A 2015 report by the World Jewish Restitution Organization highlighted several instances of museums resorting to these tactics when faced with Nazi restitution claims, including the Toledo Museum of Art, the Detroit Institute of Arts, and the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The report also charged that “a number of U.S. museums, by seeking to block adjudication on the facts and the merits of claims, are failing to live up to the spirit of international declarations regarding restitution of Holocaust-era assets.”

Primary among those declarations are the 1998 Washington Conference Principles, which have become a touchstone for how to handle Nazi-looted art cases across the art world as a whole. The 44 signatory nations called on institutions to identify work Nazi-looted work not yet restituted and then work “expeditiously to achieve a just and fair solution” in such cases.

In Dr. Oetker’s commitment to reach equitable settlements, one sees an adherence to the spirit of the principles many museums sidestep in court. “It’s a positive thing for a private corporation—which has no duty to the Washington Principles or to even think about them—to take that approach to a work of art in their possession,” said O'Donnell.

Pierre Valentin, a partner at Constantine Cannon LLP in London who is working with Dr. Oetker on its restitution efforts, wouldn’t reveal the specifics of company’s internal processes. He also eschewed direct comparisons to the Washington Conference Principles, citing that they don’t apply to private collections.

“We think that by following our guidelines we achieve an equitable outcome on a case by case basis,” he said.

Even outside of the Washington Conference Principles, institutions work under a different framework that that of Dr. Oetker. Museums facing restitution claims have consistently asserted a responsibility keep work in their collection and on view to the public. Private collections have no such commitment—and, in most cases, might prefer to avoid public links to the Nazi regime by retaining looted work.

The Oetker Collection is not rushing to finish its provenance research. The first round audit of just the collection’s paintings is currently slated wrap up at the end of 2017. And if new data becomes available or new information comes to light, that process could continue beyond that.

“It’s going to take as long as it takes,” said Valentin.