News:

Ruling Paves Way for Transfer of Art Trove Including Nazi-Looted Works

By Melissa Eddy and Alison Smale

BERLIN — A German man who had stashed a trove of art that included works stolen by the Nazis was of sound mind when he bequeathed his father’s collection to the Museum of Fine Arts in Bern, Switzerland, a Munich court ruled on Thursday. The decision paves the way for the 1,500 artworks to be transferred.

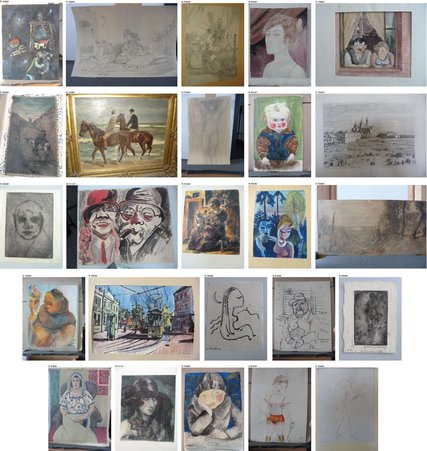

Some of the roughly 1,500 artworks Cornelius Gurlitt kept for years in his Munich apartment.

Cornelius Gurlitt drew up his will in 2014, months after the existence of the collection in his Munich apartment came to light, capturing the world’s attention. But a cousin, Uta Werner, had challenged that decision.

The discovery stunned not only the art world — Jewish groups and historians denounced the decision by the Bavarian police to keep their knowledge of the collection’s existence secret for nearly two years after seizing it in 2012.

The international outcry led the German government to set up a team of international researchers tasked with determining whether the art might have been seized by the Nazis from Jewish owners.

The reclusive Mr. Gurlitt died in 2014 at age 81, months after drawing up his will and leaving his collection to the Kunstmuseum Bern. At the time, he was under the care of a court-appointed legal guardian, but the court rejected Ms. Werner’s argument that he was not of sound mind.

“The Kunstmuseum Bern was legitimately named as sole inheritor in the will,” the court said in a statement. Ms. Werner, in an effort to prevent the artworks from leaving Germany, had argued that her cousin was suffering from psychological problems when the will was drawn up. The court said it could not establish that Mr. Gurlitt “suffered from a so-called delirium when he drew up his will.”

In a statement, the Kunstmuseum said it welcomed the decision with “a sigh of relief,” adding that the ruling would allow the museum to “finally intensify” preparation for exhibitions in Switzerland and Germany, and allow it to support the efforts to determine the works’ rightful owners.

Ms. Werner said she regretted the court’s decision and would have her lawyers examine whether there were any further legal steps that could be taken to keep the works in the family, and in Germany.

The works have remained in the custody of the German government while a team of researchers appointed by the authorities continues the painstaking work to establish their provenance. The researchers have determined that a handful of works were either looted by the Nazis or bought at below-market prices.

The commission’s full report is expected in January, and the museum in Bern has pledged to continue the research.

When the first research team was established in January 2014, it set out to determine the ownership history of those works with questionable backgrounds within a year. But as the months wore on, the enormous size of the task became apparent, and the government in Berlin extended additional funding.

Despite efforts that began even before Mr. Gurlitt’s death, experts have been able to establish ownership for only five of the hundreds of works whose provenance was in doubt.

The two most prominent were handed to their rightful owners in 2015. A painting of a woman in a white blouse embroidered with flowers, “Femme Assise,” or “Seated Woman/Woman Sitting in an Armchair” by Matisse, went to the descendants of a Paris art dealer, Paul Rosenberg. A Max Liebermann oil painting, “Two Riders on the Beach,” was handed over to the descendants of David Friedmann, a Jewish lawyer in Breslau.

Now 1,005 works remain to be researched, said Andrea Baresel-Brand, who took over the team at the start of this year. Of those, the team has identified 680 that may be looted art pieces; breaking it down further, they have listed 91 of those works with a detailed ownership history that requires more research.

To keep everything straight, the team has established a system of color coding, with red for clear or very probable cases of looting, green for a work that was not looted and amber for doubtful cases, Ms. Baresel-Brand said. Among the last group, there are many works for which the historians have simply been unable to find the necessary documents to fully establish the chain of ownership.

Ms. Baresel-Brand stressed the extraordinary difficulty of tracing ownership back over the decades, despite a multinational team combing archives in Germany, France, the United States and elsewhere.

“Most will stay amber, unfortunately,” Ms. Baresel-Brand said in an interview.

She cited as an example two works, which the researchers are almost certain were looted by the Nazis, but which are missing ownership details for some periods of time.

One is a sculpture by Auguste Rodin: a small marble figure, “La Femme Accroupie,” or “Crouching Woman.” Researchers have been unable to plug a gap in the 1940s, or find the record of when Hildebrand Gurlitt, Cornelius Gurlitt’s father, acquired the statue, which was later photographed as part of his collection, Ms. Baresel-Brand said.

After months of effort, her group will have to classify the piece as amber, “a dead end, where we have done all we can,” she said.