News:

Will Victims of Nazi Art Thieves Finally Get Justice?

Some courts say too much time has passed for descendants to get back the masterpieces the Nazis stole. Families say no—and Congress is stepping in.

Remember The Monuments Men—the 2014 film starring a host of notables from Bill Murray to George Clooney to Matt Damon? The one about Nazis stealing the art of their Jewish victims, as well as other prized works maintained in Nazi-occupied Europe, and the quest led by an international team of art historians to locate, save and return them to their owners or their owners’ families?

The Hollywood depiction involved a generally happy ending, but for many of the families affected by Nazi theft in the realm of art confiscation, the real-life version has not ended well at all. Even today, decades later, some families are still chasing down prized masterpieces and fighting in court for restitution of ownership—including here in the United States.

Meet Marei von Saher. She is the daughter-in-law of Jacques Goudstikker, a Dutch art collector who fled Nazi-dominated Europe and whose firm was subsequently forced to sell his art to the Nazis. Von Saher is on a mission to get back the art that was taken from her father-in-law’s firm, despite some fairly challenging circumstances. For one thing, Goudstikker himself declined to pursue restitution—albeit via a system that imposed substantial costs and that the Dutch government in 1998 dubbed “cold and even callous.” And for another, well, a lot of time has passed since World War II.

Von Saher has won back ownership of over 200 paintings formerly belonging to her father-in-law’s firm. But there are two outstanding items she wants back and she is not getting—for now, anyway.

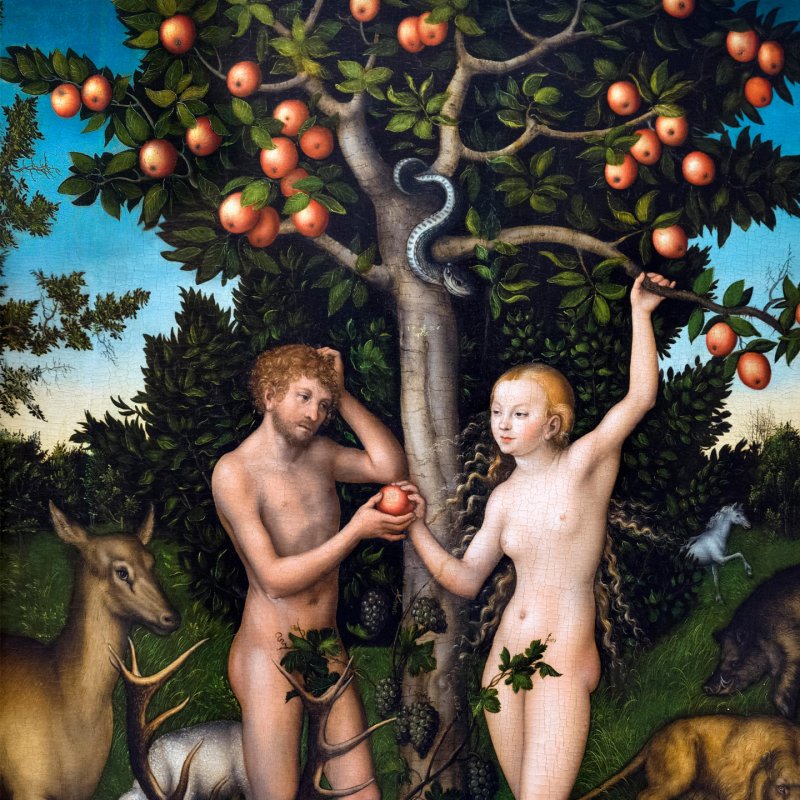

Last month, a U.S. District Court ruled that the early 16th-century paintings, “Adam” and “Eve” by Lucas Cranach the Elder, will remain the property of their current owner, Pasadena’s Norton Simon Museum. A major hurdle standing in Von Saher’s way, legally, is the delay in seeking their return (though another issue may be that they were owned by von Saher’s father-in-law’s firm and not by him personally). She is hardly alone; in 2006, two cases were brought by the heirs of Nathans, a banking family in pre-war Germany, against the Detroit Institute of Art and the Toledo Museum. Those heirs also lost, due to the “delay” aspect.

Unsurprisingly, Von Saher is appealing the ruling in her case. Meanwhile, critics of post-war restitution efforts are seeking to pass legislation in Congress that would make return of such works to families and heirs legally easier.

The Holocaust Expropriated Art Recovery (HEAR) Act would broaden the statute of limitations relevant to claims at the federal level like von Saher’s, thus limiting the extent to which “delay” can be considered a factor in determining whether to restore ownership. According to proponents of the legislation, it specifically “gives claimants an opportunity to have their case decided on the merits by establishing a nationwide window of six years within which such claims can be brought to recover art that was unlawfully lost due to theft, seizure, forced sale, sale under duress, or the like because of racial, ethnic, or religious persecution by the Nazis or their allies during the period from January 1, 1933, to December 31, 1945.”

The argument is that just as normal limitation periods do not and ought not apply where genocide is concerned, they similarly should not apply where related activities—like the confiscation of art belonging to Jewish victims—are involved. That is especially so, say backers, given the fact that “restitution” processes have been known to give Nazi-stolen art back to former Nazis who confiscated it in the first place, and presumably also given the fact that the location of some stolen art has only recently come to light, or remains unknown.

It is also so, they say, because of the uniquely horrific, massive nature of the Holocaust. The idea is to ensure that claims for restitution are decided purely on facts and merits, as opposed to limitation period concerns. The Senate Judiciary Committee has already held hearings on the legislation, a reason for hope on the part of the families of victims trying to get their ancestors’ property back.

But does the HEAR Act go far enough, or is it too limited? The fact is that while The Monuments Men raised awareness of the very extensive theft of Jewish-owned (and other European) art that occurred at the hands of the Nazis, that is hardly the only example of a ruthless, evil, totalitarian regime confiscating the treasures of a victimized population, either out of pure, Goring-esque hoarding instinct, or out of a desire to enrich in more basic economic terms.

ISIS is currently looting and selling antiquities as a method of self-finance, exploiting what Scottish archaeologist Donna Yates calls “a broken system” with regard to preventing the illicit sale and purchase of culturally significant art and artifacts. Also exploiting the system, apparently, are individuals looting and illicitly selling antiquities from Egypt, Libya, and Yemen.

Then there is the matter of the ongoing attention that looters—many of whom allegedly organize and communicate via online Russian archaeology forums—have apparently devoted to ancient sites in Crimea, now annexed by Russia itself. Of course, before and as the Iron Curtain fell, Communist countries confiscated private property en masse, including cultural treasures owned by prominent families. That is, in fact, part of the story that Norton Simon tells to buttress its claims of rightful ownership of “Adam” and “Eve” (which the museum contends were owned, then taken from, and then restored to the noble Russian Stroganoff family—though this remains far less than certain).

While the circumstances are indeed different to what occurred at the hands of the Nazis, and Hermann Göring, specifically, one could argue it is prudent to make provision for dealing with art confiscation, looting, stealing, forced sale and so on more broadly than HEAR does, given some of the events we see playing out today.

Still, for those interested in maximum protection of property rights, as well as righting wrongs and deterring truly abhorrent behavior going forward, what HEAR attempts to do at least presents a starting point, and a focus for debate about the matter of how we deal with the lingering effects of the Holocaust more than 70 years later. It may also provide a vehicle for Von Saher and the Nathans, and other families, to get their relatives’ property back, museums’ desires to keep the art be damned.