News:

Yeshiva University Returns Historic Rabbinical Documents

By Sophia Hollander

The collection, which spans 30 volumes and is valued at $250,000, disappeared during WWII

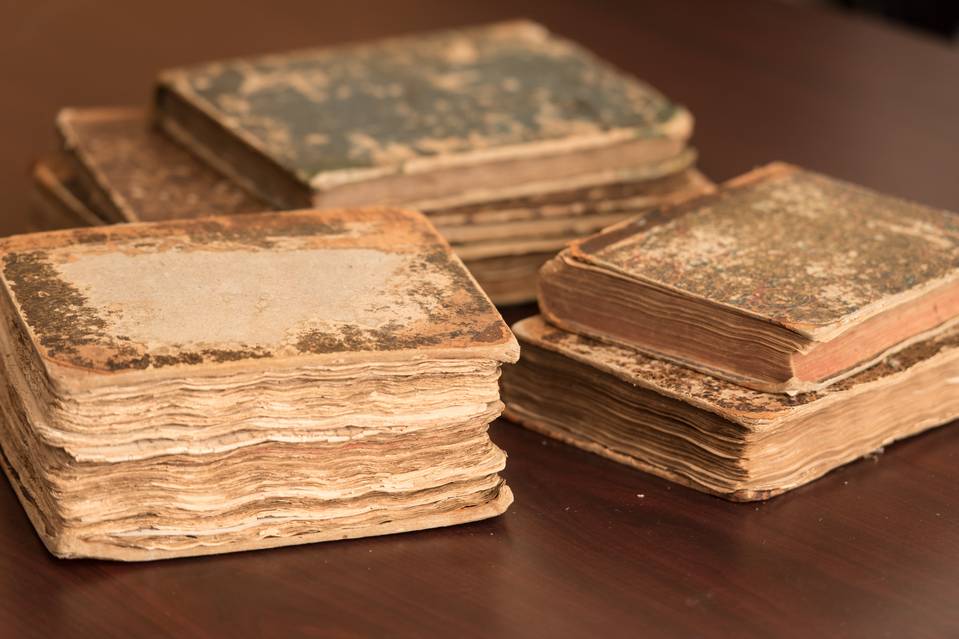

Part of a collection of rabbinical writings and commentaries, which were returned to their owners, the Auerbach family, by Yeshiva University this week.

For more than 200 years, the rabbis of the Auerbach family passed along a growing collection of rabbinical writings and commentaries to their sons, in a collection that ultimately spanned as many as 30 volumes and close to 10,000 pages.

By 1940, as the Nazi pressure on Jews in Berlin intensified, the volumes disappeared. This week, they went home.

Yeshiva University, which acquired 23 volumes starting in 1954, transferred its collection back to Rabbi Raphael Auerbach, the eighth-generation descendant of the original author. It is currently valued at $250,000.

“We thought it was the right thing to do,” said Shulamith Berger, curator of special collections at Yeshiva University. “We’re sort of proud that we could be the custodians and guardians of these manuscripts.” Otherwise, she said, “I don’t know what would have happened to them.”

The earliest document is dated 1701 and the collection went on to include extensive writings from Rabbi David Sinzheim, who negotiated with Napoleon for Jewish freedoms and became the first chief rabbi of France.

Rabbi Sinzheim was related by marriage to the Auerbach family, which had its own rabbinical dynasty in Germany, said Rabbi Auerbach. By 1935, the documents had passed to Rabbi Hirsch Binyomin Auerbach, living in Halberstadt. He lent th

e collection to a rabbinical seminary in Berlin for safekeeping as the Nazis gained power.

In 1938, Rabbi Auerbach was forced to flee Germany after a brief imprisonment in Buchenwald, a concentration camp. In 1940, the seminary was closed and looted by the Nazis. The collection disappeared.

“He spoke about it with such sorrow,” said Rabbi Auerbach’s son Raphael, now 66 years old and a rabbi in Jerusalem. “He felt always to be blamed because he got it from his father who got it from his father who got it from his father and he was the one to lose it.”

After the manuscripts disappeared from the Berlin Seminary, “there is a gap in the story,” Rabbi Auerbach said.

He theorizes they might have been taken to the U.S. by an American serviceman. His lawyers wonder if they were targeted for inclusion in a museum the Nazis planned for what they hoped would become an extinct group of people.

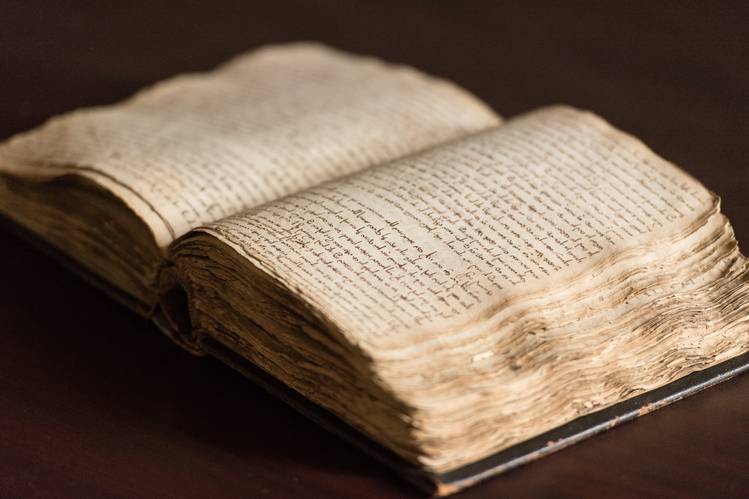

Rabbi Auerbach plans to assemble a team to publish the manuscripts, a painstaking project given the cramped lettering on the aging pages.

What is known is that the volumes resurfaced in 1954 in a bookseller’s shop on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. The proprietor approached Yeshiva University to purchase the collection, but the price—$1,500—was too steep. The manuscripts were later acquired by a private buyer and donated to the university, which has maintained them ever since.

In 2013, Rabbi Auerbach reached out to two lawyers with experience in Holocaust-restitution cases, Mel Urbach and Markus Stöetzel. Rabbi Auerbach still had the receipt his father received from the Berlin Seminary in 1935 detailing the loan, making his ownership claim unusually clear for a manuscript case, they said.

The university didn’t balk.

Its willingness to simply give the documents back set “a unique precedent,” Mr. Stöetzel said, noting that they frequently face resistance, especially in Germany. “Without any dispute, without any arbitration, without any legal issues, they simply said, ‘we are willing to do the right thing.’ ”

As part of the agreement, the university received permission to digitally publish the manuscripts on its website to facilitate access for scholars.

The manuscripts were written during a tumultuous time in Jewish history. The French Revolution brought legal equality to the Jewish community—only to see those freedoms compromised several years later during the Reign of Terror, which barred religion and targeted religious leaders, said David Sorkin, a professor of Jewish European history at Yale University. “It’s a time of major upheaval,” he said.

In the documents, Rabbi Sinzheim references hiding from his enemies. He was later invited by Napoleon to help evaluate whether equality for Jews was a legacy worth preserving from the revolution, historians said.

“He had a reputation as a giant of Talmudic learning that set him above his contemporaries,” said Jay R. Berkovitz, chair of the department of Judaic and Near Eastern studies at University of Massachusetts Amherst. “He was known for his skill and bridging between the demands of citizenship and Jewish observance.”

As a result, he continued, “he’s certainly up there among the first modern Jews in the sense as we know it, struggling to bridge between two worlds.”

Rabbi Auerbach said he planned to assemble a team to publish the manuscripts, a painstaking project given the cramped lettering on the aging pages, which include scribbles on the back of other documents like a bar mitzvah invitation from 1752.

“I feel that is my duty and that is my privilege to publish those manuscripts,” he said. “I believe that those manuscripts would not have survived without the help of God, but God has got his good agents.”