News:

Why One Museum Is Fiercely Fighting the Return of Nazi ‘Looted’ Artworks

By James Tarmy

Inside the protracted $250 million battle for the Guelph Treasure.

It’s hard to imagine anyone wanting to fight the return of artwork stolen from Jews during the Holocaust, even museum academics who have an interest in keeping the works in their collections. Not only does there seem to be a moral imperative to right these nearly century-old wrongs. On the face of it, such battles are simply bad public relations.

Yet the past decade has seen a series of high-profile, protracted restitution battles across the U.S. and Europe. The case of the so-called Gurlitt hoard, wherein more than 1,200 pieces of (mostly) stolen art was discovered in a Munich apartment in 2012, has yet to be fully resolved. A few years before that, the heirs of Jewish banker Paul von Mendelssohn-Bartholdy settled a restitution case against New York's Museum of Modern Art and Guggenheim Museum out of court; at issue were two world-class Picassos worth an estimated $150 million.

The most recent case to make headlines (although the case is close to seven years old) is the fight over the so-called Guelph Treasure, a medieval horde of religious objects. The dispute made its way from German courts to the U.S., where on Oct. 30 the defendant, the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation, filed a motion to dismiss.

It's been a long battle, but both sides are deeply entrenched. Here's why:

The Art

The Guelph Treasure is a collection of 82 medieval German ecclesiastical art pieces, most of which are encrusted with precious stones and made of some combination of gold, silver, and copper. The collection was first housed at the cathedral in Braunschweig, where it was embellished over the course of several centuries. It formally passed into the possession of the princely house of Guelph in 1671. The objects were sold in 1929 to a consortium led by four Jewish art dealers.

How It Ended Up With the Nazis

The dealers, Zacharias Hackenbroch, Isaac Rosenbaum, Saemy Rosenberg, and Julius Falk Goldschmidt explicitly purchased the collection in order to flip it for a profit. They had the bad fortune of buying it, for 7.5 million reichsmarks, just weeks before Wall Street's crash of 1929 triggered a global economic depression. Suddenly, flipping wildly expensive religious art objects was a dicey proposition.

Golden icon with Demetrios, from the Guelph Treasure.

The dealers printed elaborate catalogues, marketed the treasure across Europe, and eventually sent it on a tour of the United States. It took five years to sell 40 pieces for a total of 2.5 million reichsmarks. (The Cleveland Museum of Art is the proud owner of six.) By 1933, when the Nazis came to power, the consortium was 5 million reichsmarks in the hole, with 42 objects left to sell.

The dealers then approached the Prussian state. In 1935, after prolonged negotiation with state officials, including Hermann Goering, the consortium sold the remaining 42 works for 4.25 million reichsmarks, netting about a 10 percent loss on their initial purchase. The Guelph Treasure has since stayed in the collection of the Prussian state and is currently on permanent display at the Museum of Decorative Arts in Berlin.

The Restitution Claim

The front cover of a book from the Guelph Treasure, covered in silver, gilt, stone, and rock crystal.

Almost immediately after the Nazis came to power, they passed repressive laws impeding Jews’ ability to conduct business. They excluded them from the legal and civil services, and in 1935, with the passage of the Nuremberg Laws, eliminated their right to German citizenship. In this environment, Jews were often forced to sell possessions for significantly less than value in order to survive. In this prewar climate, three members of the consortium emigrated; the fourth died in 1937.

The Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art—a set of guidelines created in 1998 that all German museums have agreed to follow—dictate that any art object sold by Jews for less than its fair value during this period (Jan. 30, 1933, through 1945) is a candidate for restitution. This period includes the Guelph Treasure, whose worth is now estimated at $250 million.

In 2008, descendants of the consortium members filed a restitution claim against the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation, a state-run foundation that oversees Berlin's art collections. Legal wrangling went on for four years, at which point both parties agreed to arbitration hearings by an advisory commission convened by the German government. The commission ruled against the descendants, saying that the consortium got a fair-market price. Far from selling under duress, the commission stated, the consortium had been attempting to unload the Guelph Treasure for years. The commission pointed to correspondence among consortium members celebrating the sale.

Reliquaries of the Guelph Treasure stand on display at the Museum of Decorative Arts in Berlin on Feb. 26, 2015.

A year later, the heirs filed a restitution claim in the U.S.

“Look, in our view, there really isn’t any question that this was a fair-market transaction,” said Nicholas O’Donnell, a lawyer representing the heirs. “It’s absurd to argue that they had anything close to bargaining power.” No matter how forcefully a European Jew was able to negotiate with Hermann Goering in 1935, he was not negotiating from a position of equal strength. Whether or not money changed hands, the transaction was, the plaintiffs argue, theft. As for the fact that the dealers (almost) recouped their investment? “If you steal my car and I say it's worth $50,000 and you say, ‘No, it's worth $10,000,’ you don't get to keep the car because you're right about its value,” O’Donnell said.

The German Defense

This is not a clear-cut case. Hermann Parzinger, president of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation (and formerly a noted archaeologist), argues that German museums have a moral obligation to investigate every restitution claim thoroughly. In the last 20 years, his organization has conducted internal reviews and fielded approximately 50 restitution claims. About “98 percent of the time, we restituted the works,” he said.

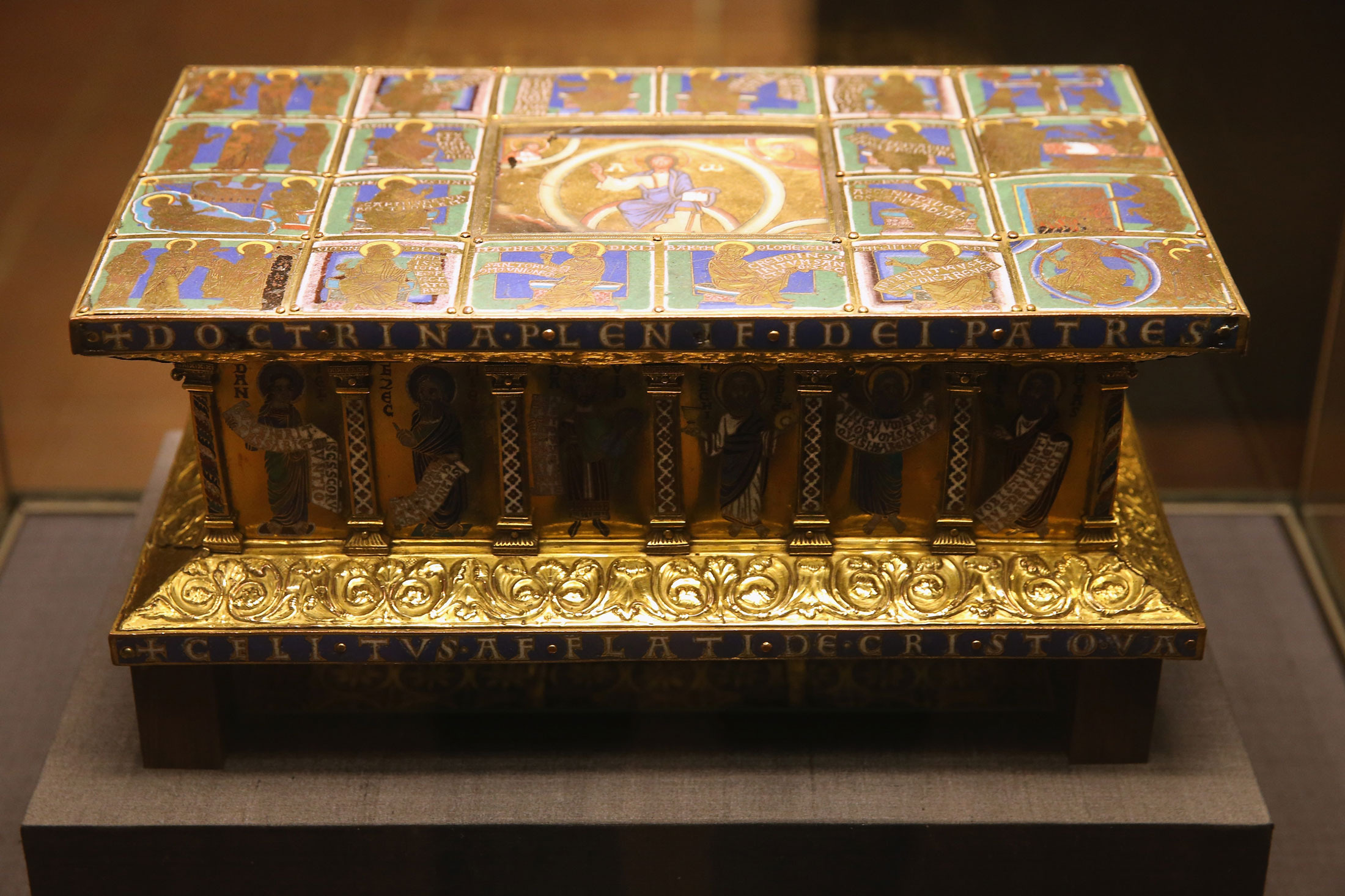

The Portable Alter of Eilbertus on display at the Museum of Decorative Arts in Berlin on Feb. 26, 2015.

In the case of the Guelph Treasure, he said, “the basic point is that no non-Jewish art seller could have gotten a better price when you see the situation at the time.”

“They say that in 1935 it wasn’t possible for there to be a fair exchange between Goering and the Jews,” Parzinger continued, “that there was this fat, disgusting Hermann Goering sitting at the table facing these poor art dealers, but this was not the case.”

Parzinger, president of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation.

Instead, he said, the art dealers (and the Guelph Treasure) were in Amsterdam, where German influence was minimal. Correspondence, he said, shows that the dealers initially asked for 5 million reichsmarks, the Prussian state (using Dresdner Bank as an intermediary) countered with an offer of 3.7 million reichsmarks, and the final 4.25 million reichsmarks figure came as a compromise; One of the art dealers was so pleased with the sale that he gave the Prussian state an ancient glass artifact as a gift, said Parzinger.

As further proof that none of the members of the consortium considered the sale forced, one of the dealers negotiated with the West German government to regain some lost property in the 1950s and '60s. “There was no word of the Guelph Treasure” in the negotiations, Parzinger said. “If it was really sold under pressure, why didn’t they put it on the [negotiating] table?”

Cross from the Guelph Treasure (Bode Museum, Berlin)

Ultimately, Parzinger said that he sees nothing wrong with the impulse to call the sale into question. “We don’t just want to be the winners of a legal case, we also want the public to be convinced that this is the right decision,” he said. For every question posed by the heirs, “we tried to investigate and get answers, and I feel that we have very good answers.” The claimants, Parzinger said, have “no real hard facts,” and their argument rests simply on “moral pictures.”

What Comes Next

Now that the Prussian Heritage Foundation has filed its motion to dismiss, attorney O’Donnell, has until the end of January to file opposition. At that point, the Prussian Heritage Foundation will have an opportunity to reply; only then will a judge decide whether the case goes forward.

The 12th century dome reliquary of the Guelph Treasure stands on display at the Museum of Decorative Arts in Berlin on Feb. 26, 2015.