News:

The Mysterious Mr Slomovic

By David D'Arcy

"Cézanne to Picasso: Ambroise Vollard, Patron of The Avant-Garde," which premiered at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Sept. 14, 2006-Jan. 7, 2007) and is soon to open at the Art Institute of Chicago (Feb. 17-May 12, 2007), is an unprecedented exhibition. Galleries filled with paintings -- 100 in all -- by Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin and Pablo Picasso bear witness to the wide reach of the pioneering dealer who showcased the modernist avant-garde and modernized the business of selling art in the 1890s and early 1900s.

The pictures on the wall stress the dealer’s unerring taste, rather than his oversights -- he was, for instance, relatively late in his support for Picasso and slow to see the value of Gauguin’s paintings from the South Seas, and he went to his grave as an admirer of Jean Puy. Still, the exhibition itself reveals little about Vollard’s character or business dealings. For that, one can turn to his classic, albeit self-serving, autobiography, Recollections of a Picture Dealer, first published in English in 1936, or to the 450-page exhibition catalogue, which includes 22 essays on the art merchant whose portrait would be painted again and again, by everyone from Picasso and Auguste Renoir to Pierre Bonnard and Georges Roualt.

The catalogue’s detailed timeline, though exhaustive, is still far from complete. Once Vollard dies in a car crash in 1939, the dispersal of his art holdings becomes complicated. Vollard’s estate was split between his brother, Lucien Vollard, and Madelaine De Galea, Ambroise Vollard’s longtime mistress and fellow reunionnaise -- both were born in the remote Ile de la Réunion, a French colony in the Indian Ocean. But hundreds of works from Vollard’s inventory also ended up in the hands of Erich Slomovic, a young Croatian Jew who had come to Paris in the mid-1930s and befriended the aging dealer.

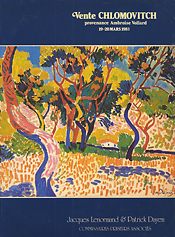

Information on Slomovic is not easy to find, yet one notable source is the catalogue for a curious auction scheduled at Drouot in Paris in 1981. Citing non-payment since 1940 for a safe deposit box rental, the Societe Generale in Paris announced that it was auctioning "La Collection Chlomovitch, Provenance Ambroise Vollard" -- 180 drawings, trial proofs and paintings by Andre Derain, Henri Matisse, Cézanne and others, most of which once belonged to Vollard.

The pictures had supposedly been deposited at the bank by Slomovic in the name of his father. The trove also included drawings, prints and photographs, some autographed with fond messages by Jean Cocteau, Matisse and others. Photos of Slomovic with Bonnard, Marc Chagall, Fernand Léger and Aristide Maillol were in the Drouot catalogue, and also for sale.

The sale never took place -- it was canceled in the face of lawsuits from heirs of both Slomovic and Vollard, and claims on the trove by the Yugoslav government. The story that subsequently emerged is complicated, even by the standards of World War II art looting.

The version told by relatives who claimed to be the young Yugoslav’s heirs is that Erich, born in 1915, arrived in Paris in 1936 or 1937 as an aspiring art collector and impresario in his early 20s, star-struck by art’s beau monde world and determined to obtain pictures from famous artists and dealers. Surviving photographs show Slomovic as a young man with dark delicate features and a trimmed moustache, fastidiously groomed during his visits to bearded artists in their paint-spattered studios.

Slomovic relatives’ account comes from Stolen Art, an investigation into the Slomovic case by Victor Perry, who died before the book was published in Israel in 2000. Perry’s book includes interviews with Yugoslavs who knew Slomovic and with Yugoslav officials.

Slomovic intended to make his reputation and (some say) his fortune, apparently, by importing avant-garde culture from Paris to Yugoslavia. He pursued artists ranging from Cocteau and Bonnard to Chagall and Le Corbusier. Slomovic is said to have boasted of commissioning le Corbusier to build a modern art museum in Belgrade.

Slomovic’s pivotal relationship seems to have been with Vollard, who was 70 years when he met the young Yugoslav. Vollard offered more than a huge inventory. He was the gatekeeper who could open access to any artist in Paris. A bond grew out of that first meeting -- a father-son bond, which would have been a unique kind of bond for the taciturn dealer. Had the young man tapped into Vollard’s famous vanity?

Whatever the nature of that relationship -- and it could well have had homoerotic elements -- Slomovic obtained pictures, books and letters that Vollard inscribed to him. Vollard also wrote letters of introduction to Bonnard, Rouault and others. Those artists inscribed their own dedications to works that they gave to the young man. On a drawing of a grinning fawn, Jean Cocteau wrote slyly. "Memory of a cruel world."

After Vollard’s death in a car accident in July 1939, Slomovic continued acquiring art, probably with the help of Vollard’s brother Lucien Vollard, and possibly in collaboration with Martin Fabiani, a Corsican mafioso (and later Nazi collaborator) who had gained the confidence of Lucien, a drug addict who always needed money.

(Many art insiders now believe that the accident which killed Vollard was, in fact, a murder, which they say was part of a plot concocted by Fabiani. No one was ever investigated or charged in Vollard’s death. For further details, see my article "Ambroise Vollard" in the September 2006 issue of Art + Auction magazine.)

By 1940, the Nazi blitzkrieg had already struck Poland and would soon crush France. Slomovic rented his safe deposit box in his father’s name at the Societe Generale and returned to Yugoslavia. He took another 400 works of art with him, thanks to the assistance of Yugoslav diplomats in Paris. Slomovic originally planned an exhibition of the works in Belgrade, the country’s capital, but mounted the show of paintings, watercolors, drawings and books in a fine arts center in Zagreb instead. Many of these works are now held by the National Museum in Belgrade (and none are included in the present Vollard exhibition).

Yet who actually owned these pictures when they left Paris? In a French court in the 1980s, Slomovic’s heirs claimed that the works were a gift from Vollard to the young entrepreneur, so he could launch a museum in Yugoslavia with Vollard’s imprimatur. According to Vollard’s heirs, the trove was no gift, but rather works put out on consignment. It was a common practice, they said, for Vollard to organize traveling exhibitions through other dealers, dressing up his gallery’s inventory -- all of which was for sale -- as the "Vollard Collection."

Given, consigned, or just stolen -- every speculation into the transfer of works of art from Vollard to Slomovic is shrouded in the fog of war. No living witnesses remain.

In any case, soon after the 1940 Zagreb exhibition came down, the Nazis marched into Yugoslavia, and Slomovic, fearing the worst as a Jew, fled with his family to a village outside Belgrade. In a farmhouse there, he hid his pictures in four metal containers and one round cylinder behind a false wall. Eventually, local people betrayed the family to the Nazis, who detained Slomovic along with his father and brother. Soon the three were transferred with other Jews to an execution camp. They were gassed in a truck that was converted into a mobile killing unit. Erich Slomovic was 27.

Somehow, Slomovic’s mother, Roza, survived in the village and saved the works until the war’s end, only to die in a train wreck while taking them to Belgrade. A relative salvaged the objects, and sent them to be stored in Belgrade, where the new Yugoslav communist government was consolidating power.

After the war, the Yugoslav government seized the cache of artworks, claiming that Slomovic had died with no heirs, and that the property belonged to the new Yugoslav state. People in art circles in Belgrade at the time told Perry, the author of the book Stolen Art, that the government learned of the existence of the cache after bugging the U.S. embassy. One diplomat, a "Mr. Clifford," mentioned on the telephone that he planned to buy some art from the woman who was holding it, who needed cash desperately. Soon after that call, Yugoslav agents had the pictures.

By the early 1960s, word of the art trove began leaking out -- first in Yugoslavia , then abroad. In 1964, the French art historian Denis Rouart published The Unknown Degas and Renoir in the National Museum of Belgrade, a catalogue of 110 pictures that also mentioned Slomovic and referred to the "gift" from Vollard to Slomovic. Though he suggested that such a gift would be "incredible," Rouart claimed that Slomovic had planned "to leave the whole collection to the Belgrade Museum, as an independent unit which would bear his name."

Little happened until 1981, when the auction at Druout was announced.

While the parties fought it out in court, a baffling contribution to the debate came from Yugoslavia in the form of a movie about the dealer and his protégé. Titled The Donator, the feature was directed and co-scripted by Veljko Bulajic, who typically made Soviet-style epics of World War II battles between Nazis and partisans. The villain is a Nazi major who is in Yugoslavia shopping for Hermann Goering’s art collection, and the central story involves thwarting the Nazi officer’s efforts to find and Aryanize the hundreds of pictures from Paris.

Never mind that the Germans wouldn't have known about Slomovic’s art holdings. In flashbacks, the film introduces Slomovic and Vollard. The dealer is portrayed as an aging bachelor, effeminate and vain -- Vollard is said to have spoken in a high voice, with a lisp -- as if to hint at a homoerotic relationship between the two principals.

Eventually, the film ends as Slomovic dies in a gas chamber, and Yugoslav patriots keep the art from falling into German hands, dutifully handing it over to communist officials after the war. Predictably, the dramatization of Vollard’s relationship with Slomovic is clearly in the service of the Yugoslav government’s claim to ownership of the Vollard pictures that it had possessed since the years after World War II.

The film’s release in Yugoslavia coincided with expanded publicity about the "secret" collection, minus any information about why the government sought to keep the collection secret in the first place.

This story does not crescendo to a resolution. After years of litigation over the pictures from the safe deposit box at the Societe Generale -- during which time everyone in Paris who had any contact with Vollard testified that he was neither gay nor particularly generous (Daniel Wildenstein said that "Vollard wouldn’t give away the time of day") -- the Vollard heirs, the Slomovic heirs in Israel and the U.S. reached a settlement in the 1990s, dividing the works among them.

The truth may be just as anticlimactic. The French journalist Jean-Paul Morel, who is preparing a long-awaited biography of Vollard, thinks that Slomovic was probably representing Vollard’s brother, Lucien, and Martin Fabiani, the dealer who took over Vollard’s gallery in Paris. Had the war not intervened, the young man might have had a career shuttling back and forth from Belgrade to Paris, bringing minor French art to a backwater where anything from Paris was worth buying. Instead of making a name as a would-be Vollard (and not just a footnote to the Vollard story), Slomovic, at 27, became another anonymous corpse in Hitler’s war against the Jews, and Yugoslavia got his collection by force majeure.

How Slomovic got all those pictures remains a mystery. So does the fact that the safe deposit box, registered under a Jewish name, remained intact throughout the Nazi occupation, when French officials were all too happy to relieve Jews of their property. Slomovic’s receipt for the initial rental of the box was "lost," but we do know that the box was opened and its contents transferred several times after the war. Did anything disappear?

Perhaps this isn’t the end of the Slomovic story. When the Met’s Vollard show travels to the Art Institute of Chicago and the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, attention will continue to focus on all things Vollard. Perhaps die-hard Vollardistes who haven’t gotten their fill will journey to Belgrade. Perhaps some of them will dare to inquire how so many pictures from Vollard’s gallery ever ended up there.

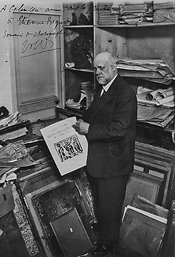

Thérèse Bonney’s Vollard at 28, rue Martignac (ca. 1932), with an inscription to dealer Etienne Bignou reading "To someone who loves paintings so much."

Erich Slomovic with (clockwise from top left) Aristide Maillol, Pierre Bonnard, Marc Chagall, and Henri Matisse

Cover of the catalogue for the "La Collection Chlomovitch, Provenance Ambroise Vollard" at Drouot in 1981

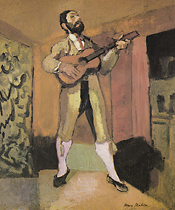

Henri Matisse’s Le Guitariste Debout (1903), featured in the 1981 Drouot sale

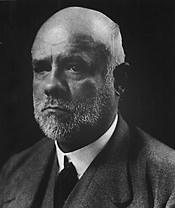

Ambroise Vollard, as pictured in the frontispiece of the 1981 Sale Chlomovitch Catalogue

Paul Gauguin’s Trois Tetes de Tahitiens, monotype, featured in the 1981 Drouot catalogue

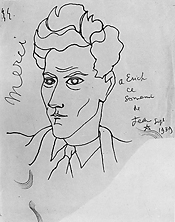

Jean Cocteau’s 1939 self-portrait drawing, inscribed to Erich Chlomovitch, in the 1981 Drouot catalogue

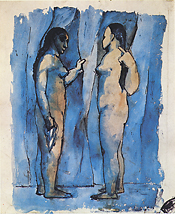

Pablo Picasso’s Deux femmes nues, 1906, in the 1981 Drouot catalogue

Paul Cézanne’s Portrait of Emile Zola, 1861, in the 1981 Drouot catalogue

Cover of Denis Rouart’s The Unknown Degas and Renoir: A Newly Discovered Collection, published in 1964

Edgar Degas’ Bust of Man in Soft Hat (ca. 1867), from the collection of the Belgrade Museum

Edgar Degas’ The Bath, n.d., in the Vollard Collection at the National Museum of Belgrade

A monotype by Edgar Degas from the Vollard Collection in the Belgrade Museum

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Bathers, ca. 1882-84, in the Vollard Collection at the National Museum of Belgrade

Ljubomir Todorovic played Erich Slomovic in the 1898 movie Donator

DAVID D’ARCY is a correspondent for the Art Newspaper, a contributing editor at Art & Auction and a regular critic on the "Front Row" program on BBC Radio.