News:

Swiss Museum Says It Would Return All Nazi-Looted Works

By John Revill and Bertrand Benoit

Bern Institute Will Decide in Six Months Whether to Accept Trove Left to Museum by German Recluse

The Swiss museum that has inherited but not yet accepted the collection of Cornelius Gurlitt, the late son of one of Hitler's art dealers, wants any works found to have been looted by the Nazis returned to their original owners, its director said.

The assurance is likely to come as a relief to heirs of Holocaust victims who have been seeking to recover artworks in Mr. Gurlitt's trove. Those efforts were thrown into doubt by the German collector's death this week. Still, it could be months before any pieces are returned to families with restitution claims.

Matthias Frehner, director of the Kunstmuseum Bern, told The Wall Street Journal on Thursday that the museum's 12 trustees and its president would decide within the next six months whether to accept Mr. Gurlitt's will, which bequeaths the recluse collector's entire estate to the museum.

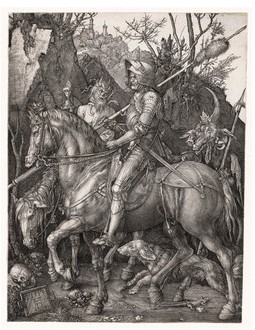

This Albrecht Dürer piece belongs to the cache of about 1,400 works.

If it does, the museum would abide by a 1998 international agreement known as the "Washington Principles," under which art institutions must return any looted art or compensate their original owners, Mr. Frehner said in an interview at his office in Bern. The museum learned only after Mr. Gurlitt's death this week that he had bequeathed the disputed collection to the Bern institute.

"Switzerland has agreed to [the Washington Principles] and the gallery will comply with these," he said. "I don't want artworks shown here which are doubtful and which could have been looted or stolen."

Christopher Marinello, a lawyer for one of the families seeking restitution, welcomed the museum's response to its surprise inheritance. "I'm not surprised but certainly glad that the museum adheres to international codes of ethics," he said. Mr. Marinello is seeking the return of "Woman with a Fan," a 1923 Henri Matisse painting that is believed to be one of the most valuable pieces in the Gurlitt art trove, on behalf of the family of late Parisian art dealer Paul Rosenberg.

The existence of Mr. Gurlitt's will, written this year, was revealed after the 81-year-old died in Munich on Tuesday. His main art trove of some 1,400 pieces—many of which are suspected to have been stolen by the Nazis—was seized by German authorities in early 2012 as part of a tax investigation but was only made public this past November.

A smaller part of the collection, originally kept in a house in Salzburg, Austria, and now in storage in Vienna, was never seized. These artworks and the rest of Mr. Gurlitt's estate, including his properties, were also bequeathed to the Bern Museum.

In April, Mr. Gurlitt reached a deal to have the works held by Bavarian prosecutors combed for stolen art and those pieces returned to their previous owners' families. In exchange, the German and Bavarian governments agreed to return those pieces not thought to be looted to Mr. Gurlitt and finance the research into the works' provenance.

Mr. Frehner said he would prefer the German government-appointed task force of experts that has begun researching the collection to finish its work rather than have the Kunstmuseum take over the investigation.

"The task force is installed, they are believable, they are neutral, so I think it would be in the interest of all if they continued and finished their work," he said. The Kunstmuseum would likely have to pay for any research it decides to carry on its own.

August Matteis, a lawyer suing Germany on behalf of David Toren, a claimant to a Max Liebermann painting in Mr. Gurlitt's collection, said he was pleased the museum intended to return any looted art if it accepts the collection. But Mr. Matteis said he remained skeptical of the German government's efforts and didn't plan to drop the lawsuit. "Germany should not be allowed to abdicate its responsibility by giving stolen property to any third party, much less a third party designated by Cornelius Gurlitt," he said.

Mr. Frehner says the Bern museum will decide in the next six months whether to take the art trove.

Representatives of the museum will travel to Munich next week to meet Christoph Edel, a Munich lawyer who had been Mr. Gurlitt's court-appointed guardian, and members of the task force. Additional meetings may also take place with the Bavarian government.

Whether the museum accepts the collection would depend on the content of the collection, the works' state of conservation and the clarity of the legal situation, Mr. Frehner said. If it doesn't accept the works, it is possible the collection could go to distant relatives of Mr. Gurlitt or, if no heir is found, to the German state.

If the museum accepts Mr. Gurlitt's estate, Mr. Frehner said it may put up some minor works for sale. "The collection is so famous," he said. "It was talked about around the world, but nobody knows what it is exactly."

"If there are redundant works I think we could sell them and buy something which makes sense in our collection," Mr. Frehner said.

Mary M. Lane contributed to this article.

http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702304655304579549880169810884?mg=reno64-wsj&url=http%3A%2F%2Fonline.wsj.com%2Farticle%2FSB10001424052702304655304579549880169810884.html