News:

A Hidden Art Trove and a Lost Relative

By Catherine Hickley

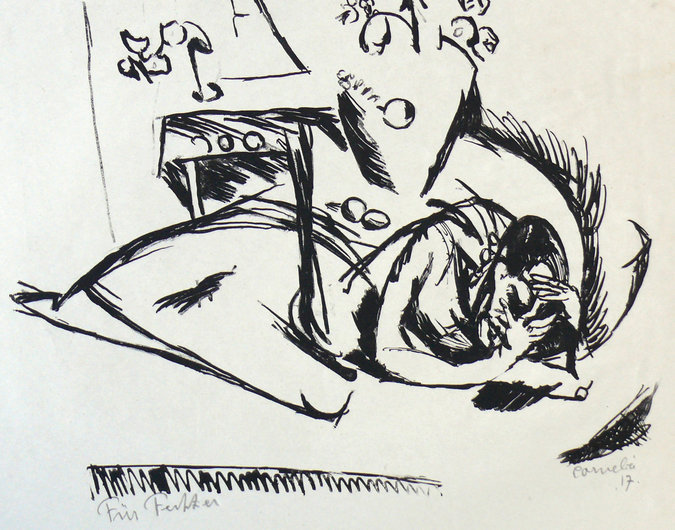

A lithograph by Cornelia Gurlitt of a woman grieving, which she dedicated to her lover, the art critic Paul Fechter.

HOCHSTADT, Germany - Last November, Hubert Portz was at his home in Hochstadt, southwest of Mannheim, reading a story in the morning newspaper when he came across a familiar name, causing his heart to skip a beat.

The story was about a spectacular trove of art found in the Munich home of the elderly son of an art dealer who worked for the Nazis. The cache would soon spark controversy over Germany’s willingness to address restitution claims for Nazi-looted artworks. What caught Mr. Portz’s attention, however, was the name of the individual: Cornelius Gurlitt. For years, Mr. Portz, a psychotherapist and amateur art historian, had been intrigued about an artist named Cornelia Gurlitt and had been searching for her work.

She was Mr. Gurlitt’s aunt.

“I thought, wow, now I know where to look,” Mr. Portz said in an interview at his sunlit kitchen table this month. “I immediately wrote to Cornelius and told him about my project. There was no reply.”

A talented artist, Cornelia Gurlitt committed suicide by taking poison almost a century ago, when only in her twenties. Mr. Portz stumbled across her name four years ago while researching the Dresden art scene of her era. He began to assemble information about her and plan an exhibition of her work. It will open on April 26 in Hochstadt.

Born in 1890, Ms. Gurlitt was the elder sister of Hildebrand Gurlitt, a dealer who bought art for Adolf Hitler’s planned “Führermuseum” and acquired the cache of more than 1,200 works found in his son’s apartment. Ms. Gurlitt’s work is virtually unknown — partly because much of it is thought to have been hidden for decades in her nephew’s home, alongside the Matisses, Monets and Munchs.

Those works remain out of public reach for now. Yet some of Ms. Gurlitt’s melancholy, Expressionist images, many of them lithographs, did find their way into the possession of friends and family members.

Mr. Portz purchased nine lithographs by Ms. Gurlitt from the Galerie Joseph Fach in Frankfurt in December 2012. She had given the works to her lover, the art critic Paul Fechter, and they were later sold by his family. In March 2013, eight months before Ms. Gurlitt’s trove was made public, Mr. Portz put an advertisement in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung requesting information on any art by Ms. Gurlitt. A Frankfurt collector responded, offering him 11 lithographs handed down by Hanns Niedecken-Gebhard, a stage director who was a friend of Ms. Gurlitt’s. Members of the Gurlitt family have loaned works from their private collections. These are all featured in the show.

“Cornelia was extraordinarily talented,” said Bärbel Fach, who runs the Galerie Joseph Fach and said she acquired the works she sold to Mr. Portz at an auction, without knowing anything about her history. “It’s a tragedy she died so young and her artistic development ended so early. I’d love to find out where the rest of her work is today.”

Mr. Portz is showcasing the pictures in the former Sparkasse bank branch next to his house that he has converted with his private funds into a bijou museum. The unfussily presented, compact show spotlights 23 works by Ms. Gurlitt alongside art by her World War I-era Dresden friends, Lotte Wahle and the better-known Conrad Felixmüller. It is titled, “A Vacant Room for Cornelia Gurlitt, Lotte Wahle and Conrad Felixmüller” and runs through June 14.

Cornelia Gurlitt in an undated photograph with her brother Hildebrand.

Against white walls, Ms. Gurlitt’s small, dark figurative works touch on grief, heartbreak, illness and poverty. They are mainly prints and drawings, with one oil portrait of Hildebrand Gurlitt and an early self-portrait, lent by other members of the family. In one lithograph, a woman lifts her arms and face to the sun — away from the suffering that surrounds her.

“I was swept up by her energy, and wanted to get to know her and write about her,” Mr. Portz said.

Ms. Gurlitt, Hildebrand and their elder brother, Wilibald, grew up in a family steeped in the arts. Their father was the rector of Dresden’s Technical University and a champion of Baroque architecture. Tall and fair-haired, Ms. Gurlitt took after him in appearance. He built her a studio in their villa.

She had some early success. In 1914, Kunstchronik magazine reviewed a group show in Chemnitz, and said her paintings showed “good promise as the Expressionist portrayal of subjective, internal experiences.”

When World War I broke out, Ms. Gurlitt volunteered for the Red Cross and went to the Lithuanian capital, Vilnius, to tend the wounded. A poignant image in Mr. Portz’s exhibition shows a nurse in a hospital tent, surrounded by the sick and wounded, her palms raised and eyes lowered in a gesture of helplessness.

A lithograph by Ms. Gurlitt of a World War I hospital tent in Vilnius, Lithuania.

Hildebrand Gurlitt later joined her in Lithuania from the Western Front, employed by the Wilnaer Zeitung, a German-language newspaper for the troops in the east. Ms. Gurlitt was determined to earn her own living, a radical ambition for a bourgeois woman of her time. She set up as an artist in chaotic, postwar Berlin. Yet she couldn’t settle and sunk into deep despair, becoming inaccessible even to her younger brother.

On a Tuesday in August 1919, according to a letter Hildebrand Gurlitt wrote to Mr. Fechter, Ms. Gurlitt visited a Berlin bakery for breakfast at 10 a.m., fell asleep and never woke again. By 4 a.m. the next day, her heart had stopped. She was 29.

Hildebrand Gurlitt sorted through her possessions after her death, and posted paintings, drawings and lithographs to family members as mementos. He kept many for himself. She was, he wrote to his mother, Marie, “the person who was closest to me.”

Mr. Fechter, her lover, wrote about Ms. Gurlitt in his 1949 book “An der Wende der Zeit” (In a Time of Change). He described her as “perhaps the most gifted of the young generation of Expressionists.”

The family story is that Ms. Gurlitt’s mother regarded her suicide as a great disgrace and burned her art. Mr. Portz doesn’t believe it. He is sure the Munich trove will contain works by her and will reveal more about her — both through her art, and through correspondence her nephew inherited. He says his fascination with her stems from his admiration for strong women who challenge men to follow their desires. For Mr. Portz, the exhibition is in part a homage to his wife, who died last year.

Now that Mr. Gurlitt has reached an agreement on the fate of his art with the German government and the prosecutor has pledged to return it, Mr. Portz is confident it will all, someday, be made public. And perhaps Cornelia Gurlitt will belatedly earn a small place in art history.

“A Vacant Room for Cornelia Gurlitt, Lotte Wahle and Conrad Felixmüller” runs from April 26 to June 14 at the Kunsthaus Desiree, Hochstadt. A catalogue is published by Knecht Verlag.