News:

Artworks lost in Nazi era at heart of hunt

By Sam Whiting

When Holocaust survivor George Rynecki died in 1992, he left a war memoir in the trunk of his car, bequeathing the family legacy to his only grandchild, Elizabeth. "It was like, 'Whoosh,' " recalls Elizabeth Rynecki, who is still feeling the blowback of 700 paintings by her great-grandfather that went missing after the war. She set out to find them, a search that has now taken 22 years and may take 22 more.

"Not a lot of art survived the Second World War," Rynecki says, "and this art has the added dimension that it was done by a Jewish artist and that it portrayed the Polish Jewish community that vanished."

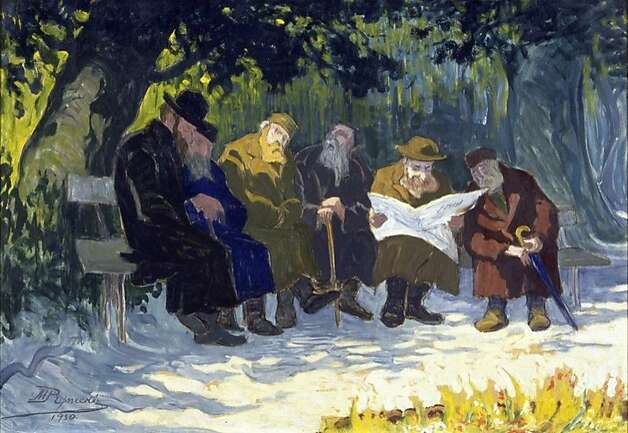

The art that vanished was made by her great-grandfather, Moshe Rynecki, who depicted life in Warsaw in the years between the wars, in oils and watercolor, charcoal sketches and sculpture. In her long odyssey to locate it, Rynecki has had a website for 15 years and a film project for five.

True story

Neither of these media ventures has done for the cause what "Monuments Men" will, when it opens on Friday. The true story of a squad of soldiers out to rescue important and valuable works of art stolen by the Nazis, "Monuments Men" stars George Clooney as the hero, supported by Matt Damon.

The hero of "Chasing Portraits" is Elizabeth Rynecki, 44, of Oakland, supported by her father, Alex Rynecki, 77, of Sausalito. A scholarly type with a master's degree in rhetoric, Elizabeth Rynecki is uncomfortable with the notion of making a documentary film about herself. But there is no other way to tell the story.

"I'm the heir," she says while sitting in the living room of the Sausalito home she grew up in, surrounded by 18 examples of what she is the heir to. She's not bragging when she says this. A painting by Moshe Rynecki sells for around $700.

"They are not worth a lot," she acknowledges. "He's not a well-known or highly valued artist."

This may work to her advantage. There is no money to be made. She is not out to sue anybody to get ownership of the art - she already has more than she has wall space for. She just wants to know what happened to it.

Historian, not claimant

"I am acting as a historian," she says, "not as a claimant." (For nearly 70 years, many families whose art was stolen, lost or confiscated have sued to have it returned.)

The history that Rynecki is following is based on the memoir found in her grandfather's trunk. It goes back to the turn of the century, when Moshe Rynecki and his wife, Perla, ran an art store in Warsaw to support his painting.

"He was somewhat successful. He showed in several gallery exhibitions and art salon shows in the inter-war years," Rynecki says. "He is mentioned in many books about Jewish artists from that period."

The family lived above the store, and as the Nazi invasion became imminent, Moshe divided his collected works into six or eight bundles then stashed them with Gentiles in and around Warsaw for safekeeping. He made a list of locations and distributed three copies. Each move was to ensure survival, except his last.

"Moshe went into the Warsaw ghetto willingly because he wanted to be with his brothers and sisters," Rynecki says, "and if that meant death, so be it."

It did, in a German concentration camp in 1943. Perla and their son George, through a combination of guile, fake paperwork and convincing accents, avoided the camps and survived.

70-year mystery

The war ended, and they followed the list to recover the six or eight bundles. But they found only one, in a basement, and that has led to the 70-year mystery. Rynecki doubts the Nazis who invaded Poland would have bothered to haul away the art because it depicted Jews in the ghetto, living the type of life the Nazis were out to erase from history. It's more likely that whatever the Nazis found would be shredded and trashed.

"Warsaw was a destroyed city, so I would assume that some burned," Rynecki says. "I also have evidence that some of the hidden bundles made it through the war."

Carrying whatever art they could, maybe 120 paintings, Moshe's widow and son made their way to Italy and the United States, under sponsorship of a family in Denison, Texas. The art they carried finally ended up in the home in Sausalito where Elizabeth Rynecki was raised the only child of an only child. The home is tucked into the hillside and faces north so no direct light would hit the paintings.

"This is Moshe" she says, introducing a 1934 self-portrait of the artist, a sad-eyed man who seems to be speaking out from the frame, telling his great-granddaughter to keep looking.

"It's really haunted me more and more," she says. "I really feel that I have a responsibility to the Jewish community and to the world of art history to share this art."

With two sons in elementary school, Rynecki works for her father in a real estate concern with holdings in Humboldt County. This allows her the time to pursue lectures at colleges and museums, and to run the website, www.rynecki.org which guides viewers to a 9-minute trailer for the documentary-in-progress "Chasing Portraits."

It's been an arduous hunt. She located six works with a collector and four with a man in Toronto. That lead sounded so promising that she flew up a few months ago to see them, and for her trouble got a tip on seven more artworks in Israel, and one in Poland.

She also has found photographs of 13 paintings but has no idea whether they still exist or where. In November, after many years of prodding, the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw sent photos of 17 Ryneckis in their collection, which she will be visiting later this year. She only counts pictures that she can see and verify against her tally.

Emotionally nervous

"I'm very nervous about going. Not for any safety reasons, just emotionally," she says. "But the time has come that I must go and see the paintings in person."

When Munich dealer Cornelius Gurlitt was busted late last year with an apartment full of art lost in the war, Rynecki was immediately willing to go there, too. Following up on a vague description of a painting of men playing a game at a table, she followed the lead. It went nowhere, leaving 630 paintings and other works still unaccounted for. She's looking for them in bunches, and she's looking for them one by one.

"I don't think this project will ever be completed," she says. "Somebody has something in their basement, and they don't know it."

http://www.sfgate.com/default/article/Mystery-of-ancestor-s-lost-in-Nazi-era-art-haunts-5190708.php