News:

Family, ‘Not Willing to Forget,’ Pursues Art It Lost to Nazis

By Patricia Cohen and Tom Mashberg

Lt. Alexandre Rosenberg of the Free French forces pounded on the boxcars. Hold your fire, he told his men. There might be prisoners inside the train they had stopped outside Paris in August 1944. Slowly, a few of the heavy doors slid open, and a handful of worn German soldiers straggled out.

Inside, the French found the cargo the Germans had been guarding, crates jammed with artwork: sculptures, drawings and framed paintings, some stacked against one another like bread slices, their signatures visible.

Picasso. Renoir. Braque. Cézanne.

The lieutenant did not need to read the names. He had seen many of the works before, hanging in the Paris home of his father, Paul Rosenberg, then one of the world’s leading dealers in Modern art.

Since that day, three generations of Rosenbergs have been engaged in a painstaking search for hundreds of artworks that were looted from their family by the Nazis. This month their hunt led to Norway, where the family is negotiating for the return of a Matisse that has hung for 45 years in the Henie Onstad Arts Center, a museum founded by the skater Sonja Henie and her husband.

“We are not willing to forget, or let it go,” said Marianne Rosenberg, Alexandre Rosenberg’s daughter, a New York lawyer. “I think of it as a crusade.”

The Rosenberg cache represents just a tiny part of what some experts say are roughly 100,000 pieces — worth perhaps $10 billion — still missing from Nazi plundering, but few victims have been as unyielding, or as successful, as this family in reconstituting their cultural legacy.

The Rosenbergs have scoured auction catalogs, worked with Interpol, dragged museums to court and even resorted to buying back their own property to retrieve more than 340 of the roughly 400 works they lost.

Few can claim so many victories. “They are part of the 5 percent of those who have been successful,” said Marc Masurovsky, a founder of the Holocaust Art Restitution Project. “They set an example of how restitution should take place.”

The chase has rarely been easy. Despite the victories, the Rosenbergs’ efforts, like those of others who have tried to regain property that disappeared under the Third Reich, have been plagued by frustration and deceit, Ms. Rosenberg said.

Although dozens of countries signed international agreements in 1998 and again in 2009 that pledged to resolve claims of families like the Rosenbergs quickly, there are no mechanisms to enforce them. As a result, many attempts to recover stolen art have required years of bruising, often unsuccessful battles with institutions, bureaucracies and courts.

In that sense, the Rosenbergs’ experience is both extraordinary and typical, said Jonathan Petropoulos, the former art research director for the Presidential Advisory Commission on Holocaust Assets in the United States.

“They are exceptional because Paul Rosenberg was a tremendously important art dealer, and much of their museum-quality art was easier to trace,” Dr. Petropoulos said. “On the other hand, the Rosenbergs are representative because there is much that they have not been able to locate. Most Holocaust victims and their heirs have not recovered their stolen property.”

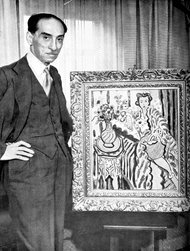

Paul Rosenberg, circa 1915

The Rosenbergs were helped by their wealth, their luck and a long trail of paper. Anticipating war, Paul Rosenberg shipped some of his inventory abroad before the Wehrmacht rolled into Paris in June 1940, and was quickly able to re-establish his business on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, from which he also pursued his missing art.

The Rosenberg gallery closed in 1987, when Alexandre Rosenberg died; his widow, Elaine, still lives in the town house it once occupied. On the fifth floor, she employs a full-time archivist to maintain the family’s records — 250,000 documents, letters and photographs — neatly organized in beige boxes that line the walls and closets.

“That’s what sets them apart,” and enabled them to prove their claims, said Christopher A. Marinello, the executive director of the Art Loss Register, a company that tracks stolen art and has negotiated for the family, including in its effort to regain the Matisse now in Norway.

Paul Rosenberg, a meticulous, elegant man, kept extraordinarily detailed records to document not only his business but his role in nurturing the spread of Modern art after World War I. Visitors to his silk-lined gallery at 21 rue La Boétie could examine works by Rodin, Cézanne, Monet and Modigliani. (That address was the title of a memoir published last year by Rosenberg’s granddaughter, Anne Sinclair, the French journalist and ex-wife of Dominique Strauss-Kahn.)

Rosenberg’s remarkable eye and passion prompted Braque, Picasso and Matisse to choose him as their exclusive representative. At Rosenberg’s urging, Ms. Sinclair recalled, Picasso moved next door, where he could hail his dealer — “Dear Rosi” — through the window.

“Dear Pic,” Rosenberg would reply.

Mr. Rosenberg in 1941 with a painting by Henri Matisse.

The declaration of war in the fall of 1939 prompted the Rosenbergs to leave Paris and store some of their art in a bank vault and a house near Bordeaux. Within months, they left the country just days ahead of the German Army, crossing into Spain and making their way to New York.

Some of the 400 or so Rosenberg works were saved by the 1944 interception of that train, No. 40,044, outside Paris — an event that became the inspiration for the 1964 movie “The Train,” with Burt Lancaster.

The rest have been traced piece by piece.

Within weeks of the war’s end, Paul Rosenberg traveled to Paris to recover paintings that were stored in the Jeu de Paume museum, a clearinghouse for Nazi booty, and to Switzerland, where his art had been bought by unscrupulous collectors.“He would go to the ends of the earth,” Mr. Masurovsky said; art “was his lifeblood, and it was like taking his babies away.”

Some efforts ended in disappointment. Before he died in 1959, Paul Rosenberg tracked a Matisse to the south of France and sued the owner. The judge, Ms. Rosenberg said, ruled in favor of the defendant — the judge’s brother.

In 1971 Alexandre Rosenberg ended up buying back a Degas, “Two Dancers.” “I do not like so enriching the successors to thieves,” he wrote in a letter, “but have come to learn that the defense of one’s own, and one’s family’s interests, is somewhat like politics and indeed life itself. It is principally the art of the possible.”

He was luckier retrieving a Braque, “Table With Tobacco Pouch,” in 1974. The day after he recognized it in a French auction catalog, he flew to Paris, and arrived at the auction with the police. The seller was Josée de Chambrun, the daughter of the former Prime Minister Pierre Laval, a leader of the Vichy government. She handed over the art.

The Rosenbergs got some help in their search in the mid-1990s when several books on the Nazis’ art crimes were published. In 1997, for example, the granddaughter of a couple who had donated Matisse’s “Odalisque” to the Seattle Museum of Art contacted the Rosenbergs after seeing the work in Hector Feliciano’s book “The Lost Museum.” The museum agreed to return it in 1999 after the family sued.

The family also got back “Waterlilies” by Monet. The Art Loss Register confirmed its identity in 1998, when the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Normandy lent it to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Recovered from the private collection of the Nazi foreign minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop, “Waterlilies” was one of an estimated 2,000 artworks that the French government reclaimed after the war, but said it could not identify the owners.

The family’s most recent discovery — “Woman in Blue in Front of Fireplace” — occurred last summer when this Matisse was on loan to the Pompidou Center in Paris from the Henie Onstad Arts Center. According to the center’s director, Tone Hansen, the museum is reviewing the origins of 18 prewar works as a result of this case. Of the Matisse, she said, “We are not ready to draw any final conclusions.”

As for the rest of the artworks that are still missing, Ms. Sinclair said, the recovery would probably fall to a fourth generation of Rosenbergs.

“I think,” she said, “it might take our grandchildren to find them.http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/27/arts/design/rosenberg-familys-quest-to-regain-art-stolen-by-nazis.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0