News:

Jewish philanthropist lost in the sands of time thanks to the Nazis

Independent 4 December 2012

By Tony Paterson

A wealthy patron who funded the excavation of the priceless Nefertiti bust was airbrushed from history. Now, a hundred years after the find, his story is finally being told.

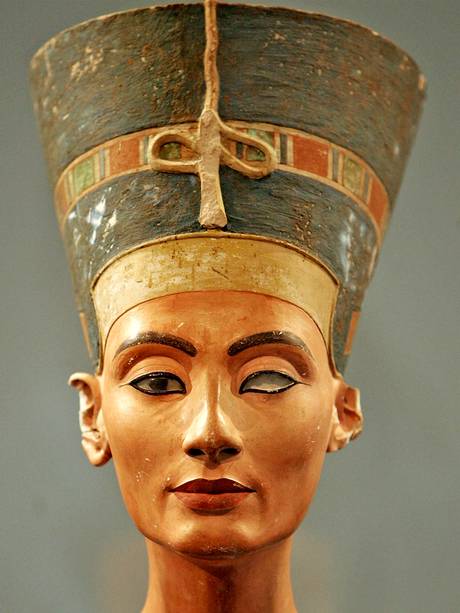

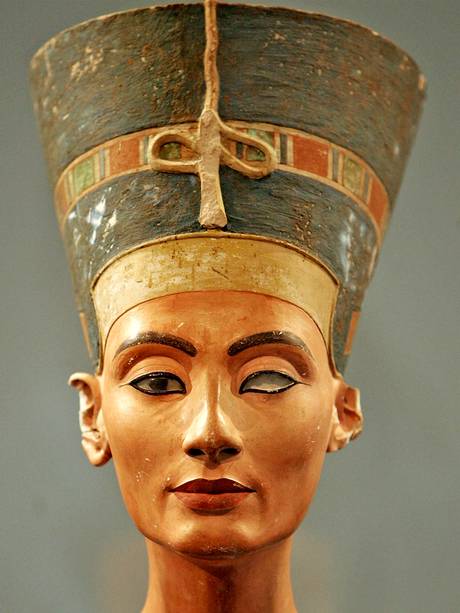

She is regarded as the ancient world’s equivalent to the Mona Lisa and this weekend the 3,400–year old bust of the Egyptian Queen Nefertiti will be the centrepiece of a grand exhibition in Berlin’s Neues Museum, celebrating her discovery by German archaeologists exactly a century ago.

The delicately featured and priceless bust of the wife of the ancient Egyptian Sun King Akhenaten has been one of the highlights of Berlin’s museum collection since it was first put on display in the city in 1923.

It was unearthed by the famous German archaeologist Ludwig Borchardt, at Amarna in 1912. He became a household name in Germany but few know the story of the wealthy Jewish patron and philanthropist who not only funded the excavation work that led to the bust’s discovery but also donated Nefertiti and scores of other ancient Egyptian artefacts he owned to Berlin’s museums. Organisers of the centenary celebrations are hoping to change that. James Simon is buried in Berlin’s Jewish cemetery. The wealthy Berlin businessman and patron of the arts was a member of the capital’s thriving pre-Second World War Jewish community. There is little doubt that without his passion for the arts and ancient history, Nefertiti would not be one of the city’s foremost attractions, viewed by half a million visitors a year.

But because Simon was a Prussian Jew, his name was expunged from German history books after Adolf Hitler’s Nazis came to power in 1933. “It was not acceptable for Simon to be recognised, like many other middle-class Jews, as somebody who had made a major contribution to German culture and done much to solve social problems,” wrote Der Spiegel this week.

Simon remained a largely forgotten figure in West Germany after the war. This weekend, his story will be told for the first time in a new television documentary about his life by the journalist and film director Carola Wedel.

Simon is described as “the most generous benefactor Berlin ever had”. Wedel’s film tells of his birth into a wealthy, liberal Berlin Jewish family in 1851. He attended a prestigious Catholic grammar school where he excelled, but his parents refused to allow him to indulge his passion and study ancient history, insisting instead that he join the family firm.

Simon Brothers was a cotton company with a turnover of 50 million Reichsmarks which netted an annual profit of 6 million. Historians interviewed in the film say the company’s wealth allowed Simon to exhibit “a degree of selflessness which is hardly conceivable by today’s standards”.

Simon donated a quarter of his income both to the arts and a whole series of philanthropic causes and social projects. His patronage for the arts began after the opening of Berlin’s National Gallery in 1876. Unlike its counterparts in Paris or London, the gallery had only a handful of exhibits.

Simon came to the rescue. In 1885 he gave a Renaissance painting to the gallery, followed by countless donations, including paintings by Rembrandt, Bellini and Mantegna, a series of works from the Middle Ages and Babylonian artefacts.

He also financed Germany’s archaeologists who were competing with their British and French counterparts to unearth the gems of ancient Egypt. According to the laws of the time, Simon was the rightful owner of half of everything they found.

When Borchardt discovered Nefertiti, it was Simon, as the bust’s owner, who arranged for it to be sent to Berlin. In 1920, he donated the bust to the city’s museums.

Simon’s generosity did not end there. In 1889 he started funding the construction of public baths. That was followed by the founding of a club for working-class children. In 1906 he opened a home for abused and disadvantaged children. As anti-Semitism began to take root in Germany, he also financed a scheme which invested millions in helping east European Jews emigrate to the Americas and Palestine.

But by 1925 Simon was in financial trouble. He was forced to close down his business, sold his opulent Berlin villa and moved into a simple apartment.

When Egypt appealed to Germany to return Nefertiti, Simon wrote to the Berlin Museum holding the bust, and reminded its directors that they had once given an undertaking to do so in the event of such a request from Cairo. But the museum’s directors refused.

Just who is the rightful owner of the Pharaonic Queen whose name means “a beautiful woman has arrived” has been the subject of a simmering diplomatic row between Egypt and Germany for decades. Cairo claims the Germans tricked the Egyptians into allowing them to take the bust out of the country. Germany maintains there was no foul play and has declined all demands for the return of the bust.

Simon was so incensed by Berlin’s refusal to return Nefertiti to Egypt, he turned down an invitation to attend the opening of the city’s famous Pergamon Museum in protest. He died alone and embittered in 1932. Eighty years after his death, Berlin is still not contemplating Nefertiti’s return but it plans a permanent tribute to its forgotten patron. A new gallery being built on the city’s Museum Island is to be called the James Simon Gallery.

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/science/archaeology/news/jewish-philanthropist-lost-in-the-sands-of-time-thanks-to-the-nazis-8382305.html

By Tony Paterson

A wealthy patron who funded the excavation of the priceless Nefertiti bust was airbrushed from history. Now, a hundred years after the find, his story is finally being told.

She is regarded as the ancient world’s equivalent to the Mona Lisa and this weekend the 3,400–year old bust of the Egyptian Queen Nefertiti will be the centrepiece of a grand exhibition in Berlin’s Neues Museum, celebrating her discovery by German archaeologists exactly a century ago.

The delicately featured and priceless bust of the wife of the ancient Egyptian Sun King Akhenaten has been one of the highlights of Berlin’s museum collection since it was first put on display in the city in 1923.

It was unearthed by the famous German archaeologist Ludwig Borchardt, at Amarna in 1912. He became a household name in Germany but few know the story of the wealthy Jewish patron and philanthropist who not only funded the excavation work that led to the bust’s discovery but also donated Nefertiti and scores of other ancient Egyptian artefacts he owned to Berlin’s museums. Organisers of the centenary celebrations are hoping to change that. James Simon is buried in Berlin’s Jewish cemetery. The wealthy Berlin businessman and patron of the arts was a member of the capital’s thriving pre-Second World War Jewish community. There is little doubt that without his passion for the arts and ancient history, Nefertiti would not be one of the city’s foremost attractions, viewed by half a million visitors a year.

But because Simon was a Prussian Jew, his name was expunged from German history books after Adolf Hitler’s Nazis came to power in 1933. “It was not acceptable for Simon to be recognised, like many other middle-class Jews, as somebody who had made a major contribution to German culture and done much to solve social problems,” wrote Der Spiegel this week.

Simon remained a largely forgotten figure in West Germany after the war. This weekend, his story will be told for the first time in a new television documentary about his life by the journalist and film director Carola Wedel.

Simon is described as “the most generous benefactor Berlin ever had”. Wedel’s film tells of his birth into a wealthy, liberal Berlin Jewish family in 1851. He attended a prestigious Catholic grammar school where he excelled, but his parents refused to allow him to indulge his passion and study ancient history, insisting instead that he join the family firm.

Simon Brothers was a cotton company with a turnover of 50 million Reichsmarks which netted an annual profit of 6 million. Historians interviewed in the film say the company’s wealth allowed Simon to exhibit “a degree of selflessness which is hardly conceivable by today’s standards”.

Simon donated a quarter of his income both to the arts and a whole series of philanthropic causes and social projects. His patronage for the arts began after the opening of Berlin’s National Gallery in 1876. Unlike its counterparts in Paris or London, the gallery had only a handful of exhibits.

Simon came to the rescue. In 1885 he gave a Renaissance painting to the gallery, followed by countless donations, including paintings by Rembrandt, Bellini and Mantegna, a series of works from the Middle Ages and Babylonian artefacts.

He also financed Germany’s archaeologists who were competing with their British and French counterparts to unearth the gems of ancient Egypt. According to the laws of the time, Simon was the rightful owner of half of everything they found.

When Borchardt discovered Nefertiti, it was Simon, as the bust’s owner, who arranged for it to be sent to Berlin. In 1920, he donated the bust to the city’s museums.

Simon’s generosity did not end there. In 1889 he started funding the construction of public baths. That was followed by the founding of a club for working-class children. In 1906 he opened a home for abused and disadvantaged children. As anti-Semitism began to take root in Germany, he also financed a scheme which invested millions in helping east European Jews emigrate to the Americas and Palestine.

But by 1925 Simon was in financial trouble. He was forced to close down his business, sold his opulent Berlin villa and moved into a simple apartment.

When Egypt appealed to Germany to return Nefertiti, Simon wrote to the Berlin Museum holding the bust, and reminded its directors that they had once given an undertaking to do so in the event of such a request from Cairo. But the museum’s directors refused.

Just who is the rightful owner of the Pharaonic Queen whose name means “a beautiful woman has arrived” has been the subject of a simmering diplomatic row between Egypt and Germany for decades. Cairo claims the Germans tricked the Egyptians into allowing them to take the bust out of the country. Germany maintains there was no foul play and has declined all demands for the return of the bust.

Simon was so incensed by Berlin’s refusal to return Nefertiti to Egypt, he turned down an invitation to attend the opening of the city’s famous Pergamon Museum in protest. He died alone and embittered in 1932. Eighty years after his death, Berlin is still not contemplating Nefertiti’s return but it plans a permanent tribute to its forgotten patron. A new gallery being built on the city’s Museum Island is to be called the James Simon Gallery.

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/science/archaeology/news/jewish-philanthropist-lost-in-the-sands-of-time-thanks-to-the-nazis-8382305.html

© website copyright Central Registry 2024