News:

Roadblocks Remain in Case of Paintings Lost to Nazis

New York Times 28 October 2010

By Judy Dempsey

BUDAPEST — The paintings — some by El Greco, others by Courbet, Velázquez, Renoir and Monet — are hanging in the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest, the Hungarian National Gallery, the Museum of Applied Arts, the Budapest Technological University and the National Museum in Warsaw.

They were once owned by Baron Mor Lipot Herzog, a wealthy Jewish patron of the arts, who lived in Budapest and died in 1934. His art collection, some 2,500 works, was seized from his family after the authorities in Hungary, which sided with Hitler, passed a decree (among more than 200 anti-Jewish decrees and laws passed between 1938 and 1944) stipulating that art that was owned by Jews be confiscated.

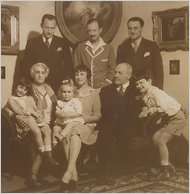

Herzog family archives

Baron Mor Lipot Herzog, sitting at lower right, with his family

Many descendants of Jews whose property — particularly works of art — was seized during World War II, as well as museums in the path of the Nazis and the Red Army, have sought and received restitution, particularly from Austria and Germany.

And European governments, including Hungary and Poland, have pushed hard since 1989 to retrieve art that was confiscated or looted from museums. But the Hungarian and Polish governments have so far refused to return works to Herzog’s descendants, leaving open one of the last chapters of World War II and the Holocaust.

The question that has puzzled and frustrated the Herzog family and others who have been active in such restitution efforts, is: What makes this case different, and so difficult?

“The paintings are part of our legacy,” David de Csepel, Baron Herzog’s great-grandson, said recently.

After trying for two decades to retrieve Herzog’s treasures, his descendants filed suit in July in the U.S. District Court in Washington against the Hungarian government. They seek the return of what they claim is more than $100 million worth of paintings.

But can filing a suit in the United States have an effect in Hungary or Poland? Possibly, said David S. Rowland, a lawyer based in New York who specializes in international transactions including the restitution of art.

“If the lawsuit was successful and a judgment in a U.S. court could be enforced in Hungary, this would clearly mean that the suit would be more than an embarrassment, ” Mr. Rowland said. “The lawsuit puts a spotlight on the case, and this may affect the behavior of the party retaining the artworks.”

He noted that there have been at least three similar suits filed in the United States in recent years, two of which, against Austria and Amsterdam, have resulted in restitution; the third, against Spain, is still under way.

What David de Csepel, the 44-year-old great-grandson of Herzog who lives in Los Angeles and filed the suit, recalls most vividly about his grandmother — the baron’s daughter — was her pride in her family and her love of art.

Erzsebet Herzog Weiss de Csepel would take him by the hand, Mr. de Csepel said, and show him photographs and paintings that had belonged to her father.

“The paintings are part of our legacy,” Mr. de Csepel said by telephone recently. “It’s appalling if you consider how they were taken in the first place; how Hungary treated the Jews.”

In 1944, between May and July, the Hungarian authorities deported to the concentration camps more than 440,000 of the 825,000 Jews living in Hungary.

“We are still being shunted around by Hungarian officials,” Mr. de Csepel said. “This is about doing justice not only for us but for other families. Hungary has done a tremendous wrong by not acknowledging where the paintings came from.”

Hungarian officials have declined to comment about the suit. Officials at the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest said that the museum was not responsible for these issues.

“The family had no other choice,” said Michael S. Shuster, the lawyer representing the Herzog descendants. “Hungary is simply not willing to step up to the plate. When it comes to restitution or the Holocaust being remembered, Jews are resented.”

Efforts of the last two decades yielded one piece of information on the Hungarian government’s position: In 2008 a letter sent by Kinga Goncz, then foreign minister, to Hillary Clinton, then a U.S. senator from New York, claimed that the museums did not have to return artworks to the Herzog family because Erzsebet de Csepel had already received compensation under a 1973 American-Hungarian claims settlement.

But Agnes Peresztegi, a lawyer and European director of the Commission for Art Recovery, a nonprofit organization that seeks justice for Holocaust victims of Nazi art theft, said the letter was misleading.

“Based on 1949 legislation, the Herzog family had received some compensation from the U.S. government, not from Hungary. The 1973 claims agreement did not cover her claim,” Mrs. Peresztegi said.

The stonewalling on any discussion of looted art and the lack of information from museums about their collections, she continued, is tied to Hungary’s past.

“Hungary has always seen itself as a victim because Hitler’s troops occupied the country when Hungary was trying to make a separate peace with the Allies,” Ms. Peresztegi said. “It was and remained a Nazi ally. There has been no historical commission set up to look at the past. There is no curriculum in the schools that deals with the Holocaust. And that is the issue: restitution does not occur without recognition of the past.”

Thousands of works were looted during World War II — about 20 percent of all Western art in Europe during the Second World War, according to the Commission for Art Recovery. When the Red Army moved across Poland into Germany in 1945, it in turn took thousands of art objects back to the Soviet Union as war booty. Since then, many European governments and individuals have been trying to retrieve art from Russia.

Some countries, particularly Germany and Austria, have actually stepped up efforts to return looted art, especially since the 1998 Washington Conference on Holocaust-Era Assets. At that conference 44 countries, Hungary and Poland among them, signed on to international principles that include identifying looted Nazi art, opening museum archives, establishing a central registry of displaced property and encouraging claims by original owners and their heirs.

Wesley Fischer, director of research at the Jewish Claims Conference and World Jewish Restitution Organization, said both Poland and Hungary have disregarded the principles. The two groups have for years lobbied governments to return art looted from Holocaust victims.

“Hungary signed up to the Washington principles but it has been two-faced,” Mr. Fischer said. “Publicly the government says it will cooperate. In practice it does not.”

Mr. Shuster, the lead attorney in the Herzog suit, said the case was proceeding under the Hague Service Convention, a multilateral treaty signed in 1965 that allows service of judicial documents from one signatory state to another without involving diplomatic channels.

“We are waiting for confirmation from the Hungarian Central Authority as to whether they will accept service,” he said.

The Polish government too has been slow to return looted art, Mr. Fischer said. “Poland, unlike most other countries in Eastern Europe, does not even have a restitution law,” he pointed out.

At the National Museum in Warsaw, Roman Olkowski, deputy director of the museum’s inventory department, has for the last 15 years been documenting the 780,000 items in the permanent galleries. Rebuilt in 1926, the museum survived, some say miraculously, the massive Nazi bombardments of the city during the Warsaw Uprising of 1944.

The museum’s goal is to make the documentation publicly available online, but Mr. Olkowski’s research has not yet been published. All information, he says, “is passed to the Department of National Heritage at the Ministry of Culture, which administers the national register of art losses.”

So far, the Ministry of Culture, headed by Bogdan Zdrojewski, has published 12 volumes of Poland’s wartime losses. They do not distinguish between art looted from the museums’ own holdings, and art from private collections. There is no registry of what Poland’s museums hold today.

Nor, said Mr. Zdrojewski, does the ministry keep any records of how much art has been returned to claimants. “The Ministry of Culture and National Heritage does not keep such blanket statistical records,” Mr. Zdrojewski said. “Art is returned directly by the institutions holding the item that is subject to a specific claim.”

Were it as simple as that. The fate of one painting is an illustration of how the Polish government and state institutions have dealt with — or, more accurately, not dealt with — claims by individuals.

The work, Gustav Courbet’s “Landscape Around Ornans,” was part of Herzog’s collection and confiscated during the early 1940s. According to Mr. Olkowski, the museum director, it was mistakenly returned by Americans to Poland in 1946 from Austria, thought to be part of a collection of other looted paintings. It has since hung in the National Museum in Warsaw. The Herzog family has sought to have the painting returned since 2001. Mr. Olkowski said the painting was not returned then because the Herzog beneficiaries did not present the complete documentation.

“The museum has to ensure that everything is well researched and documented so that art work can be given back to the right person,” Mr. Olkowski said. The case was frozen in 2004.

It took the Herzog descendants another five years to complete the documents, which Mr. Olkowski said are now being analyzed by the museum lawyers. “It should be up to the Ministry of Culture to issue guidelines and make the decision,” and not the museum, he said.

Mr. Zdrojewski of the culture ministry disagreed. “Under current legal conditions, the state is not obliged to return works of art it does not possess, as they belong to specific institutions or private individuals,” he said.

But the National Museum in Warsaw is a state-owned institution.

“It is a Catch-22 situation,” said Nawojka Cieslinska-Lobkowicz, a Pole who is an independent expert on looted art. “Without the consent of the minister of culture, no director of a public museum can remove items from the inventory of the collections.”

Furthermore, she said, no Polish government office has spoken out over the issue of looted art from individuals. The focus has been almost entirely on Poland’s own wartime losses.

Some observers say the government fears a backlash from nationalists that could reawaken anti-Semitism. Others say the country is not rich enough to return such property.

“The Jewish community was so big here that compensation would be expensive,” said Pawel Kowalski, a lecturer at the School of International Law at Warsaw’s School of Social Sciences. Before 1939, more than 3 million Jews lived in Poland, one of the biggest populations in Europe. Today, there are no more than 20,000.

Besides, added Mr. Kowalski, “many young people do not see why they have to pay the debts of a country that was not sovereign until 1989. We were so destroyed after 1945. The West did not help us and the East invaded us.”

These views partly explain why successive Polish governments have refused to deal with looted-art claims, according to Mr. Kowalski. “So much was already lost,” he said. “We now want to keep part of our history here. You have to imagine that if some Polish paintings would be taken out of Poland, the government that would do this would be thrown out of office.”

In September, after reviewing the documentation submitted by the Herzog family, the National Museum in Warsaw recommended to the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage that the Courbet painting be returned, the museum said this week in response to a reporter’s questions.

“We are waiting for the answer from the ministry,” said Katarzyna Wakula, the museum’s spokeswoman.

The Ministry of Culture and National Heritage said the case was “now under analysis at the ministry level, in particular in the context of a claim filed in a U.S. court by the heirs of Herzog.”

And David de Csepel is waiting. “This is about doing justice not only for us but for other families,” he said. “Nothing can bring back the lives of those who died in the Holocaust. We will not allow Hungary or Poland to sweep this issue under the rug.”

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/29/arts/29iht-loot.html?_r=2&pagewanted=all

By Judy Dempsey

BUDAPEST — The paintings — some by El Greco, others by Courbet, Velázquez, Renoir and Monet — are hanging in the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest, the Hungarian National Gallery, the Museum of Applied Arts, the Budapest Technological University and the National Museum in Warsaw.

They were once owned by Baron Mor Lipot Herzog, a wealthy Jewish patron of the arts, who lived in Budapest and died in 1934. His art collection, some 2,500 works, was seized from his family after the authorities in Hungary, which sided with Hitler, passed a decree (among more than 200 anti-Jewish decrees and laws passed between 1938 and 1944) stipulating that art that was owned by Jews be confiscated.

Herzog family archives

Baron Mor Lipot Herzog, sitting at lower right, with his family

Many descendants of Jews whose property — particularly works of art — was seized during World War II, as well as museums in the path of the Nazis and the Red Army, have sought and received restitution, particularly from Austria and Germany.

And European governments, including Hungary and Poland, have pushed hard since 1989 to retrieve art that was confiscated or looted from museums. But the Hungarian and Polish governments have so far refused to return works to Herzog’s descendants, leaving open one of the last chapters of World War II and the Holocaust.

The question that has puzzled and frustrated the Herzog family and others who have been active in such restitution efforts, is: What makes this case different, and so difficult?

“The paintings are part of our legacy,” David de Csepel, Baron Herzog’s great-grandson, said recently.

After trying for two decades to retrieve Herzog’s treasures, his descendants filed suit in July in the U.S. District Court in Washington against the Hungarian government. They seek the return of what they claim is more than $100 million worth of paintings.

But can filing a suit in the United States have an effect in Hungary or Poland? Possibly, said David S. Rowland, a lawyer based in New York who specializes in international transactions including the restitution of art.

“If the lawsuit was successful and a judgment in a U.S. court could be enforced in Hungary, this would clearly mean that the suit would be more than an embarrassment, ” Mr. Rowland said. “The lawsuit puts a spotlight on the case, and this may affect the behavior of the party retaining the artworks.”

He noted that there have been at least three similar suits filed in the United States in recent years, two of which, against Austria and Amsterdam, have resulted in restitution; the third, against Spain, is still under way.

What David de Csepel, the 44-year-old great-grandson of Herzog who lives in Los Angeles and filed the suit, recalls most vividly about his grandmother — the baron’s daughter — was her pride in her family and her love of art.

Erzsebet Herzog Weiss de Csepel would take him by the hand, Mr. de Csepel said, and show him photographs and paintings that had belonged to her father.

“The paintings are part of our legacy,” Mr. de Csepel said by telephone recently. “It’s appalling if you consider how they were taken in the first place; how Hungary treated the Jews.”

In 1944, between May and July, the Hungarian authorities deported to the concentration camps more than 440,000 of the 825,000 Jews living in Hungary.

“We are still being shunted around by Hungarian officials,” Mr. de Csepel said. “This is about doing justice not only for us but for other families. Hungary has done a tremendous wrong by not acknowledging where the paintings came from.”

Hungarian officials have declined to comment about the suit. Officials at the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest said that the museum was not responsible for these issues.

“The family had no other choice,” said Michael S. Shuster, the lawyer representing the Herzog descendants. “Hungary is simply not willing to step up to the plate. When it comes to restitution or the Holocaust being remembered, Jews are resented.”

Efforts of the last two decades yielded one piece of information on the Hungarian government’s position: In 2008 a letter sent by Kinga Goncz, then foreign minister, to Hillary Clinton, then a U.S. senator from New York, claimed that the museums did not have to return artworks to the Herzog family because Erzsebet de Csepel had already received compensation under a 1973 American-Hungarian claims settlement.

But Agnes Peresztegi, a lawyer and European director of the Commission for Art Recovery, a nonprofit organization that seeks justice for Holocaust victims of Nazi art theft, said the letter was misleading.

“Based on 1949 legislation, the Herzog family had received some compensation from the U.S. government, not from Hungary. The 1973 claims agreement did not cover her claim,” Mrs. Peresztegi said.

The stonewalling on any discussion of looted art and the lack of information from museums about their collections, she continued, is tied to Hungary’s past.

“Hungary has always seen itself as a victim because Hitler’s troops occupied the country when Hungary was trying to make a separate peace with the Allies,” Ms. Peresztegi said. “It was and remained a Nazi ally. There has been no historical commission set up to look at the past. There is no curriculum in the schools that deals with the Holocaust. And that is the issue: restitution does not occur without recognition of the past.”

Thousands of works were looted during World War II — about 20 percent of all Western art in Europe during the Second World War, according to the Commission for Art Recovery. When the Red Army moved across Poland into Germany in 1945, it in turn took thousands of art objects back to the Soviet Union as war booty. Since then, many European governments and individuals have been trying to retrieve art from Russia.

Some countries, particularly Germany and Austria, have actually stepped up efforts to return looted art, especially since the 1998 Washington Conference on Holocaust-Era Assets. At that conference 44 countries, Hungary and Poland among them, signed on to international principles that include identifying looted Nazi art, opening museum archives, establishing a central registry of displaced property and encouraging claims by original owners and their heirs.

Wesley Fischer, director of research at the Jewish Claims Conference and World Jewish Restitution Organization, said both Poland and Hungary have disregarded the principles. The two groups have for years lobbied governments to return art looted from Holocaust victims.

“Hungary signed up to the Washington principles but it has been two-faced,” Mr. Fischer said. “Publicly the government says it will cooperate. In practice it does not.”

Mr. Shuster, the lead attorney in the Herzog suit, said the case was proceeding under the Hague Service Convention, a multilateral treaty signed in 1965 that allows service of judicial documents from one signatory state to another without involving diplomatic channels.

“We are waiting for confirmation from the Hungarian Central Authority as to whether they will accept service,” he said.

The Polish government too has been slow to return looted art, Mr. Fischer said. “Poland, unlike most other countries in Eastern Europe, does not even have a restitution law,” he pointed out.

At the National Museum in Warsaw, Roman Olkowski, deputy director of the museum’s inventory department, has for the last 15 years been documenting the 780,000 items in the permanent galleries. Rebuilt in 1926, the museum survived, some say miraculously, the massive Nazi bombardments of the city during the Warsaw Uprising of 1944.

The museum’s goal is to make the documentation publicly available online, but Mr. Olkowski’s research has not yet been published. All information, he says, “is passed to the Department of National Heritage at the Ministry of Culture, which administers the national register of art losses.”

So far, the Ministry of Culture, headed by Bogdan Zdrojewski, has published 12 volumes of Poland’s wartime losses. They do not distinguish between art looted from the museums’ own holdings, and art from private collections. There is no registry of what Poland’s museums hold today.

Nor, said Mr. Zdrojewski, does the ministry keep any records of how much art has been returned to claimants. “The Ministry of Culture and National Heritage does not keep such blanket statistical records,” Mr. Zdrojewski said. “Art is returned directly by the institutions holding the item that is subject to a specific claim.”

Were it as simple as that. The fate of one painting is an illustration of how the Polish government and state institutions have dealt with — or, more accurately, not dealt with — claims by individuals.

The work, Gustav Courbet’s “Landscape Around Ornans,” was part of Herzog’s collection and confiscated during the early 1940s. According to Mr. Olkowski, the museum director, it was mistakenly returned by Americans to Poland in 1946 from Austria, thought to be part of a collection of other looted paintings. It has since hung in the National Museum in Warsaw. The Herzog family has sought to have the painting returned since 2001. Mr. Olkowski said the painting was not returned then because the Herzog beneficiaries did not present the complete documentation.

“The museum has to ensure that everything is well researched and documented so that art work can be given back to the right person,” Mr. Olkowski said. The case was frozen in 2004.

It took the Herzog descendants another five years to complete the documents, which Mr. Olkowski said are now being analyzed by the museum lawyers. “It should be up to the Ministry of Culture to issue guidelines and make the decision,” and not the museum, he said.

Mr. Zdrojewski of the culture ministry disagreed. “Under current legal conditions, the state is not obliged to return works of art it does not possess, as they belong to specific institutions or private individuals,” he said.

But the National Museum in Warsaw is a state-owned institution.

“It is a Catch-22 situation,” said Nawojka Cieslinska-Lobkowicz, a Pole who is an independent expert on looted art. “Without the consent of the minister of culture, no director of a public museum can remove items from the inventory of the collections.”

Furthermore, she said, no Polish government office has spoken out over the issue of looted art from individuals. The focus has been almost entirely on Poland’s own wartime losses.

Some observers say the government fears a backlash from nationalists that could reawaken anti-Semitism. Others say the country is not rich enough to return such property.

“The Jewish community was so big here that compensation would be expensive,” said Pawel Kowalski, a lecturer at the School of International Law at Warsaw’s School of Social Sciences. Before 1939, more than 3 million Jews lived in Poland, one of the biggest populations in Europe. Today, there are no more than 20,000.

Besides, added Mr. Kowalski, “many young people do not see why they have to pay the debts of a country that was not sovereign until 1989. We were so destroyed after 1945. The West did not help us and the East invaded us.”

These views partly explain why successive Polish governments have refused to deal with looted-art claims, according to Mr. Kowalski. “So much was already lost,” he said. “We now want to keep part of our history here. You have to imagine that if some Polish paintings would be taken out of Poland, the government that would do this would be thrown out of office.”

In September, after reviewing the documentation submitted by the Herzog family, the National Museum in Warsaw recommended to the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage that the Courbet painting be returned, the museum said this week in response to a reporter’s questions.

“We are waiting for the answer from the ministry,” said Katarzyna Wakula, the museum’s spokeswoman.

The Ministry of Culture and National Heritage said the case was “now under analysis at the ministry level, in particular in the context of a claim filed in a U.S. court by the heirs of Herzog.”

And David de Csepel is waiting. “This is about doing justice not only for us but for other families,” he said. “Nothing can bring back the lives of those who died in the Holocaust. We will not allow Hungary or Poland to sweep this issue under the rug.”

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/29/arts/29iht-loot.html?_r=2&pagewanted=all

© website copyright Central Registry 2024